Adam Frank is concerned with “identity” and how it relates to martial arts. He wrote the book Taijiquan and the Search for the Little Old Chinese Man.

Here’s his recent keynote address to the 2016 Martial Arts Conference.

Adam Frank is concerned with “identity” and how it relates to martial arts. He wrote the book Taijiquan and the Search for the Little Old Chinese Man.

Here’s his recent keynote address to the 2016 Martial Arts Conference.

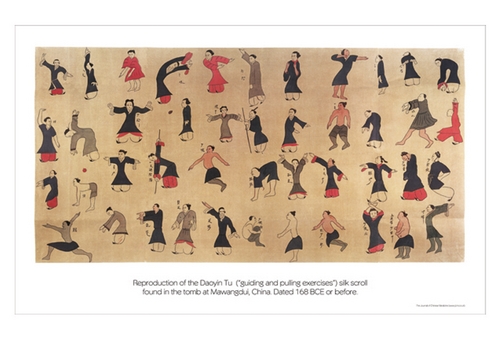

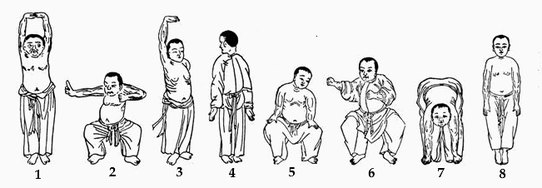

Been feeling a bit still in my hips lately, so I’m giving this simple movement flow a go for 10 minutes each morning. Try it yourself and let’s see what difference it makes.

Now that I’ve got to brown belt in BJJ I find myself wanting to refocus on the basics and get them really tight. By basics, I mean the fundamental moves that you use most of the time, rather than the spectacular spinning back takes or flying triangles that get all the attention. I mean the boring stuff. The bread and butter of BJJ, if you will.

Read the rest of this post at my new blog… BJJ Notebook

Every martial art seems to come with a bit of nonsense as part of the furniture. One of these that’s attached itself to Tai Chi is that you must learn to fight without using force. However, and to a man (because they are usually men) the people who say this seldom go beyond pushing the opponent away as the final solution to dealing with an attacker.

I think this misconception arrises because, with a little skill, you can get somebody off balance and push them quite a distance away, so long when they are unsteady, using minimal force.

But guess what – if you push somebody away… they come back! (Unless you push them off a cliff of course, but then, there’s never a cliff around when you need one, is there?) A determined attacker is not going to be impressed by how effortlessly you pushed him away. He’s going to come back and probably be even angrier than before!

I’d suggest the best thing to do with somebody you are trying to incapacitate is drop them at your feet, where you can control and restrain them until help arrives. Maybe the best thing to do is run away. But before you have that as your go-to option, consider the situation where you are with a family member and you are both under attack – what are you going to do, run away and leave them? Or maybe there are multiple attackers, in which case getting tied up with one of them on the ground is not a good idea.

Either way, the idea that you shouldn’t use force crumbles in the face of reality.

So where does this idea come from in Tai Chi? (I should note, I’ve heard the idea expressed in Aikido as well). When you’re doing Tai Chi push hands you also get a lot of comments like “too much force!”, “don’t use strength!”, which is all well and good (what they really mean is ‘don’t use brute strength’), but I think it tends to get translated into “never, ever, use force!”

Do no harm

There’s another variation on the theme which involves the notion that you should be able to subdue somebody without hurting them. Again, I’d say this was impossible. The closest I’ve seen to this idea is the sort of skill you get from BJJ where you can take a person down and mount them (sit on them) so that they can’t get up without having to punch them. You can then wait for help to arrive. Alternatively you can put them to sleep with a choke. But while they may not be getting injured, I don’t think the attacker would call it a pleasant experience!

I’m reminded of this video of BJJ noteable Ryan Hall, where he subdued an aggressive male who was trying to start a fight without throwing a single punch:

He might not have injured the guy, but he ended up putting him to sleep so he was not a threat to anybody.

So much for not using force!

Video of Ben Judkin’s Keynote at the 2015 Martial Arts Studies conference. This is a great talk which all martial arts fans should enjoy.

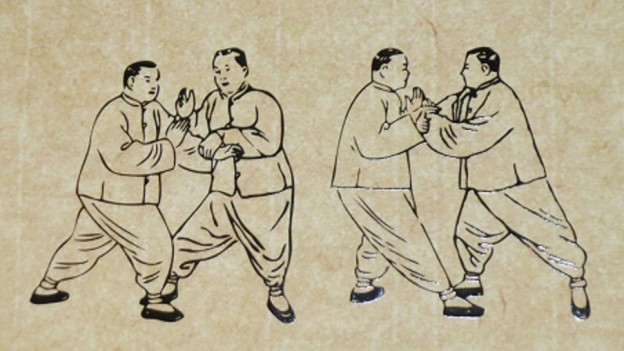

Everybody who practices Taiji and has read the Taiji Classics is familiar with the idea of using the legs as primary generators of force, rather than the shoulders and arms.

As it says in the classics:

“The chin [intrinsic strength] should be

rooted in the feet,

generated from the legs,

controlled by the waist, and

manifested through the fingers.”

Reading that, you’d think that it’s talking about simply pushing off the ground with the legs to generate force. But that’s not the whole story. It couldn’t be – I mean, a good boxer punches from his legs in a similar manner, getting the force of the whole body into the shot. Taijiquan is supposed to be ‘internal’ and involve a different way of moving than regular athletic human movements. Isn’t it?

This mention of ‘controlled by the waist’ here is the key. It’s referring to the fundamental idea in Taijiquan that the dantien area of the body (basically, the waist, but inside, not just on the surface) is controlling the actions of the arms and hands, so they don’t move independently of the movements of the body. This should be true of any Taiji movement, regardless of the particular style of Taijiquan being practiced.

This is such an important concept to Taijiquan that in a lot of interviews (like this one) Chen Xiao Wang, the head of the Chen style branch of Taijiquan, calls it his “1 principle”:

CXW: “There is just one principle and three kinds of motion. The one principle is that the whole body moves together following the Dantien. In every movement the whole-body moves together but the Dantien leads the movement and the whole body must be supported in all directions. This is very important. One principle, three kinds of motion: the three kinds of motion are as follows…First, horizontal motion, the Dantien rotates horizontally. The second kind of motion is vertical motion, the Dantien rotates vertically. The third kind of motion is a combination of the first two. Any movement that is doesn’t follow the principle is a deviation. So when we are training every day we are trying to find and reduce our deviations from the Taiji principle.”

You could also sum up this concept using the phrase, “Hands follow body”. (Later on you get ‘body follows hands’ – but let’s not worry about that right now).

It’s important to note that this mode of movement is contrary to the way we normally move in everyday life. It’s very common for people to be able to understand it intellectually, but not be able to physically embody it. It’s also very difficult to do it consistently. In Taijiquan you need to do it all the time, and without cheating! Take your mind of it for a second and you’ll find you revert to using your ‘normal’ movement again; you’ll use your shoulder and upper body to move your arms. Throw in working with a partner who is providing resistance and it becomes even harder to always move from the dantien.

Incidentally, I think one of the reasons for the incredible amount of solo form work found in Taijiquan is that you need to practice this stuff for months and years for it to become ingrained in your body, so that it becomes the default way you move, even under pressure. Hence the need for regular form practice.

So, the dantien moves, and it moves the hands. So far, so good. The next question is ‘how?’ How, exactly, can moving your legs, hips and dantien control the actions of the arms and hands?

The answer lies in the muscle tendon channels that connect the body internally. They (generally) stretch vertically from the hands (fingers) to the feet (toes) either on the front of the body (yin channels) or on the back of the body (yang channels). It’s important to note that the channels themselves don’t really cross over the body from side to side – they generally run vertically. Credit needs to go to Mike Sigman here, for introducing me to this concept of muscle-tendon channels.

The theory is that muscle-tendon channels were the precursor to the acupuncture channels that we’re all familiar with these days, and are a roadmap of the strength flows and forces of the body. If you really want to get into it, there’s a fuller explanation of the theory on Mike’s website, but the TLDNR (too long, did not read) version is basically that if you create a stretch on the muscle tendon channels from end to end, so they are somewhat taught, then you can start to manipulate them via their central nexus – the dantien – so that a movement of the dantien can power a movement of the hand (or foot). Yes, it’s more complicated than that (there is more than one dantien, for example), but that’s the basic idea.

If you remember back at the start of this blog post, I quoted some lines from the classic that says the progression in generating movement in Taijiquan starts from the bottom and goes upwards, yet at the same time we’re being told that all movement starts in the dantien, which is definitely not in the feet. So, we have a contradiction. Or do we?

Here’s the thing: If you use your legs to push upwards off the ground to generate force you get a kind of “muscle jin”, since you’re not using the power of the dantien, as described by Chen Xiao Wang. To really get to the meat of what it means to use Jin (refined force) in Taijiquan you need to learn how to send force downwards from the dantien to the ground, and bounce it back up simultaneously. So, the originator of the upwards force is still the dantien, and the general direction of force is still upwards from the feet.

For example, when you’re loaded onto the rear leg, and ready to push forward you’d actually start by sending force from your dantien area downwards, “sink the qi”, and the bounce back force that comes up from the ground is what you use to push the opponent away. It should be noted that sending forces down to the ground from the dantien and bouncing it back into the opponent is simultaneous – there’s no time delay.

The next time you go swimming dive down to the bottom of the deep end and stand on the bottom then push off the floor and send yourself upwards to the surface. What you’ll notice is that you naturally want to drop your weight down before you push up. This is a crude kind of approximation of what’s going on in a Taiji push.

I’ve just watched another YouTube video where a ‘Tai Chi master’ makes his student hop all over the place at the merest touch. I was going to link to it, but after talking about it with a friend I’m considering that might be unnecessary – maybe these Tai Chi masters that do this don’t need to be taken down – if the student is happy being made into a jumping bean, then maybe there is some sort of valuable social function being performed… even if I don’t know what it is.

As an aside, philosophically it could be strongly argued that Chinese martial arts have always had a strong performance element (via Chinese Theatre), both culturally and historically, and that the magic show is part and parcel of the deal.

But at the same time, I feel I have a responsibility to the general public about the perception of what Tai Chi is, and to the beginner looking to start learning Tai Chi, so I’m going to say something.

So, let me just say, for the record, these reactions are not what you can expect without a high degree of co-operation from your push hands partner. Tai Chi will not give you superpowers like this against a determined attacker. These problems are not unique to Tai Chi, obviously Aikido springs to mind as suffering the same ‘dive bunnies’, but somehow the vibe is different in Aikido – because of the different setting – in a Dojo, with uniforms and mats – people don’t automatically think it’s quite as ‘real’ as it is in Tai Chi superpower demonstrations. The even more dramatic flips and somersaults of Aikido Uke’s also indicate that there is compliant training going on. At least that’s how it appears to me.

These videos are done with the same tricks you find in stage hypnotism – the power of suggestion. And it you look at all these videos you start to see common traits. Here are a few you’re going to need if you want to set yourself up as a Tai Chi Magician:

1. Physical cues are important. Adopt a slight air of arrogance. Look beyond the opponent, into the distance, as if they are not there. In fact, this whole enterprise is beneath you, so remember they are nothing to you. You are looking beyond this physical realm into the spiritual, where you are dancing with the immortals. They need an enlightened master to follow, so act like one.

2. Condition your partner to be ridiculously over compliment. Maybe tell them that if they don’t ‘go with’ what you are doing, by hopping away to dissipate your force, then they will injure themselves, probably severely! This conditioning process can be subtle and take many months until they are ready for a primetime video. A few cold stares when they resist here and there, a few subtle shakes of the head when they don’t fall correctly. That sort of thing. After a few weeks or months you’ll notice they start to understand their role and act accordingly. Having a cult you’re getting them to join helps too! Get the group to reinforce your position as leader and ensure their subservience.

3. Your narrative is important – remember to say what you are about to do before you do it – key words here being things like, “down”, or “away”, so they know which direction to throw themselves in. Also say “I” a lot – remember, it’s all about you, not them.

It’s interesting that he says in his YouTube comments that he’s not very interested in fighting. (Guys that do this stuff never are, are they?) Of course, that line of reasoning is always a convenient excuse for getting out of a situation where they are asked to demonstrate these powers on somebody who is not as compliant!

The Tai Chi customer needs to treat these videos as valuable warnings. I can see how a beginner could easily start out looking to learn “Tai Chi”, not knowing what it is, and ending up in something that’s a bit cult-like with a teacher who subtly conditions and directs you to fall over at the merest touch. Trust me, manipulation is subtle and you wouldn’t even know it’s happened to you.

Don’t be that guy.

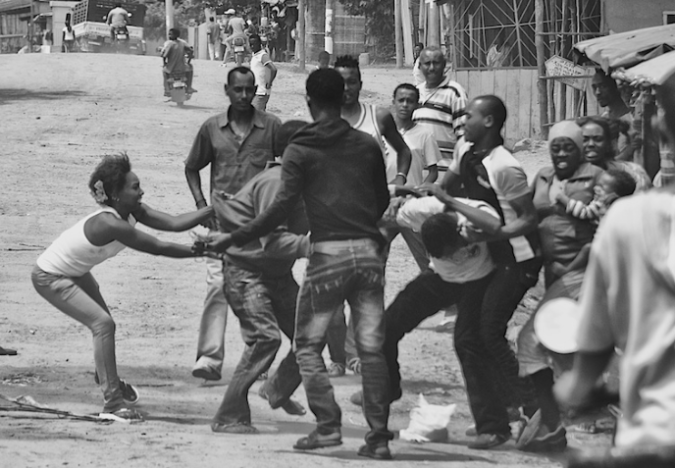

Do you remember the mantra, ‘statistics say that 90% of all fights go to the ground’? That meant we all had to learn ground fighting, and everything else was useless. Then there was the backlash to this mantra, which was, essentially: ‘that’s bullshit, what about knives and guns and multiple attackers?’, which meant that traditional martial arts still had a place even if they couldn’t succeed in the UFC.

Both camps had some hold on the truth, and these days traditional martial arts are used in the UFC more than ever before, but the problem is that the original premise was flawed – fights don’t always go to the ground, they go to the clinch, as this video showing real fights demonstrates. Unless there is a quick KO, fights go to the clinch because nobody wants to get punched in the face. It’s as simple as that. If you’ve ever done any sparring then you’ll know how instinctive it is to grab and pull the other person close, so that they can’t punch you.

Crucially, from there the most dominant grappler will always win, unless there is an intervention from a third party. I experienced this again myself this week when I met up for some ‘push hands’ with a friend. From my perspective I was trying to do push hands, but he seemed more intent on just attacking me, so I ended up just trying to deflect his strikes until I got bored of that and moved into a clinch, at which point I could easily take him down and submit him on the ground, as he has no grappling experience.

So kids, learn some form of grappling, OK?

This point deserves repeating and emphasising, as so many people don’t seem to get it, especially people who train an art full of ‘deadly’ striking techniques.

Today I watched another video of a guy lost in a Kung fu fantasy land where he deflected the non-committed attacks from his compliant demo partner, then performed a number of deadly moves on the guy’s face and neck while he just stood there and let him do it.

People, please wake up! This is not going to work!

Sadly, in my experience, you can’t change these people’s minds using something as unglamorous as logic and reason. They have a teacher who they trust more than you who is deeply invested in this stuff. Thankfully a real encounter with violence or resistant sparring session can always provide a wake up call.

Kung Fu is full of really interesting stuff, with deep cultural and historical links, and it’s fun to practice. I love it. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it so long as we understand what it is, and what it is not. Just try to remember the realities of fighting when you practice it. That’s all I ask.

As somebody not involved in academia or academic publishing, I’ve viewed Martial Arts Studies from afar for a while now, slightly scared of getting too close, in case I get bitten by the big words, like “phenomenological” and “liminoid”.

So, it was with some trepidation that I boarded the train to Cardiff for the Martial Arts Studies Conference 2016. Happily my fears were unfounded. This was my first time getting amongst the martial arts studies crowd, and what a lovely bunch of people they turned out to be! Academics are open minded, intelligent people looking to increase their knowledge through discourse. Contrasting views are often encouraged, treated with respect and pondered rather than rejected. It’s a refreshing change from the bitchy world of online discussion forums I’ve inhabited, which seem grumpy, trite and shallow in comparison. Or maybe it was just that meeting people in the flash is always so much more genuine.

Talking of which, the day started well, when I introduced myself to the random stranger I had sat next to for the first keynote and he said “Graham? Wait… are you THE Graham? The nice, funny guy from Rum Soaked Fist? Man, that place has gone downhill!” Ha! Ha! (By the way, yes, that genuinely did actually happen.)

I’ve been trying to think of how to define what martial arts studies is exactly, and I think one of the best ways to describe it is that these people are not interested in the practical ‘how to’ of martial arts, but rather what it means when people do martial arts. For example, what do the kata (or forms) of martial arts signify? What’s really going on when people perform a kata? And are they really performing, or practicing for their own sake? What are the participants of a sparring session actually engaged in? What are they really there for? How is the media selling this? Those sorts of questions.

Here are some of the titles for the talks given, to give you some idea:

“Embodied Enquiry: reflecting on embodied practices as ‘dynamic events’.”

“From Martial to the Art: Slow Aesthetics in Transnational Martial Art-house Cinema”

“Masculine identities and the performance of ‘awesome moves’ in capoeira class”.

Since we’re dealing with a subject that is physically practiced there’s always the opportunity for tactile engagement within the subjects, although this isn’t encouraged officially within conference itself (I can imagine the insurance nightmare this could lead to). But while there was no scheduled ‘hands on’ sessions, there was a bit of push hands outside in the rose garden before the conference started, which I sadly turned up to just as it finished, but I did manage to exchange some Choy Lee Fut techniques with Daniel Mroz who practiced the same style for a while, but through a different lineage. Indeed, I thought that the majority of participants in the seminar were also probably martial artists themselves. In short, it wasn’t all pie in the sky. 🙂

Ben Judkins with group photo of the CLA (Central Lightsaber Academy)

This line of thoughtful enquiry into martial arts mixed with real world interaction, humour and observation was typified by the opening keynote speech of the day by Ben Judkins, the author of the excellent Kung Fu Tea” who delivered a talk entitled “Liminoid Longings and Liminal Belonging: Hyper-reality, History and the Search for Meaning in the Modern Martial Arts”, which was about a class on Jedi lightsaber fighting that had sprung up in a mall in America, a trend that is appearing in Europe too, with Ludo Sport at the forefront. How does a lightsaber class fit into a martial arts school’s syllabus? What sort of people are attracted to it? What are they identifying with? All these questions were asked.

They take this lightsaber duelling seriously, too. I’ve got to be honest and say that it looks like great fun – I want a go.

Ludo Sport in action!

Aside from the keynotes, 4 different lectures went on at the same time, so you had to choose what you went to. So, I missed a lot of stuff I’d have like to have seen, like “Yin Yang, Five Elements and Rhymed Formulae: Traditional Chinese Concepts in the Teaching of Wing Chun”, and “Capoeira Bodies, Two Movies and Every day ‘Realities’”. I could go on – there were a lot of interesting talks I missed, but hopefully a lot of it was video taped, so I can watch it later.

Scott Park Phillips, doing his slide show thing.

I did however get to see my old friends Scott P Phillips deliver his impossibly titled, “Baguazhang: The martial dance of an angry baby-god“. As you can tell from the name of the talk, Scott likes to hit controversy head on, but give his ideas time to percolate in your mind and they start to make sense. Using copious historical examples, photos and videos, Scott exposed the theatrical and religious roots of Baguazhang, and how they are at odds with the conventional theories of the arts development, which you’d have to agree are unsatisfying and incomplete. Linking Baguazhang to the Chinese god Nezha opens many new lines of enquiry. For instance, Nezha is often depicted holding a cosmic wheel:

Look familiar?

Perhaps a bit like this?

Li Zi Ming with wind wheel swords

And those big weapons associated with Baguazhang… what do they do to the practitioner? How do they make him look?

One of the oversized weapons associated with Baguazhang.

I can’t go into the whole thing here. Scott had 3 hours-worth of material, (which had to be crammed down to 30 minutes), so he had to leave a lot of it on the table. I’d love to watch the full 3 hour version of his talk, and I hope he gets the funding he’s looking for to get it turned into a proper film. If you’re interested in his theories or helping with the project then, drop him a line or buy the book.

Daniel Mroz starting his keynote on taolu.

I also got to watch Daniel Mroz’s excellent keynote on “Taolu: credibility and decipherability in the practice of Chinese martial movement” which kind of took off from Scott’s ending point and looked a new perspectives from which the practice of taolu can be understood. Fascinating stuff, including a practical demonstration of how to add credibility to a taolu performance.

Daniel shares a method for adding credibility to taolu performance.

I noticed there were a lot of talks discussing whether or not recreating martial arts from European medieval instruction manuals – “fight books” – by groups such as HEMA can be considered a sound scientific method. I caught a couple of these talks – (the short answers seems to be “no, but it’s not without merit”). The most interesting talk I saw however didn’t seem to care about the pervading academic opinion, and was all about recreating the moves described in ancient Icelandic sagas as modern day wrestling techniques. There was some great detective work going on there.

The conference actually lasted for 3 days, but I only managed to get to the middle day, which made me wish I had more time there. There was so much I missed and so much more I’d liked to have seen.

Overall, it was a refreshingly and fascinating day that will stay with me for a long time, and it was good to meet up with old friends as well as make new ones from across the seas.

Thanks to Paul Bowman for putting on a great conference. I hope to go again.

I find it uncomfortable when ‘normal’ people find out I do a martial art. The problem is that they usually want to talk to me about it. For example, they want to tell me about their nephew/son or daughter who does “What’s that one like Karate but with the kicking in?” And 99 times out of 100 I have nothing to say about that because it has no connection with anything I do at all. Also 99 out of 100 times I find that everything they think about martial arts is based on the image of it projected by the media, thus entirely a fantasy. I try my hardest to not sound disinterested and quickly change the subject.

It’s often even worse when you do meet people who practice a martial art themselves, because quite often they’re not exactly what I’d call ‘normal’ either. They can be the sort of people who flock to “combatives” training so they can learn to defend themselves from a machine gun attack, or maybe they like wearing a uniform, hierarchy and belts, or standing in lines screaming and punching the air. Oh, and by “people” I mean “men” here. I’ve found that women who practice a martial art are usually on the level (with a few notable exceptions). Women are usually attracted to martial arts as a way to prepare themselves for the physical reality of conflict. They need to have some sort of defence if they ever find themselves in an uncomfortable situation with a larger, stronger male.

In a way I find that admitting you do a martial art to another person (if you’re a man) can be a bit like saying “Hi! There’s a high probability I’m a little odd!”

But let’s ignore the larger martial arts world and look at the small subset that is the Internal martial arts (IMA)- things like XingYi, Bagua and Tai Chi and other Chinese martial arts (CMA). I was talking about this with a friend recently. And in his own (paraphrased) words:

The problem is a lot of IMA people are looking for the “holy grail”. They are drawn to obscure jargon, high prices, “special” training and the idea that if it doesn’t work it is YOUR fault.

Certain teachers capitalises on all that very well, along with the bullying persona, being the alpha male in the room full of aiki-bunnies. People have bought so much into a particular view of MA it’s difficult for them to understand or appreciate anything outside of that view. I’m sure we both know people who would take apart 99% of IMA “masters” in a “relaxed” way, yet their work is ignored because they don’t “do it properly”.

If an IMA teacher is making constant reminders of “choking out” MMA guys and “destroying” people then it highlights his main area of worry – he knows he would struggle in either of those environments, yet he is not man enough to admit it or even – heaven forbid – go train with any of the top guys. Big fish small pond. This attitude is supported by some because it feeds into their inferiority complex and/or need to feel “special” by being accepted by the Grand Poobah. It’s largely this attitude that has almost destroyed CMA in this country – at one time CMA classes were heaving….these days…?

You can go a long way in the Chinese martial arts world, and specifically the internals, by being the guy who doesn’t mind punching civilians in the face at your seminar, to show who is top dog. If you encounter one of these controlling and manipulative individuals I’d suggest just walking away, and fast. You can’t change them, and nothing good will happen to you when you point out their obvious lies. Their followers have usually brought into the lie 100% and just shift their reality to accommodate the latest half truth or nonsense they spew.

Walk away – you don’t need these people in your life.