An important addition to the writings on Taijiquan, and Chen style in particular, that ultimately raises more questions than it answers.

I first heard about this translation of Chen Zhaopi’s 1935 book on Taijiquan by Mark Chen in an interview he did with Ken Gullette on his Internal Fighting Arts podcast. It’s well worth listening to that episode because Mark is an engaging speaker and he covers all the most interesting revelations of the book there.

I was impressed with the podcast, so ordered the book and finally managed to finish reading it recently. As already mentioned, the book contains translations of selected texts from Chen Zhaopi’s “Chen shi taijiquan hui zong” (“Chen family taijiquan selected masterworks“), published in 1935, but contains texts that claim to originate from earlier periods, authored by Chen Chanxing (and that’s where the fun starts), but let’s first take a closer look at who Chen Zhaopi was.

Chen Zhaopi is a pivotal figure in Chen family history, as he was the first Chen practitioner to move to Beijing from Chen village and teach Taijiquan commercially, in 1928. When he later accepted a teaching post at the Central Guoshu Academy in Nanjing in the south, the famous Chen Fake replaced him in Beijing in the north, securing the Chen legacy. Chen Zhaopi’s life (recounted in detail here) is a remarkable story, as he went through a series of highs and lows. His toughest time was during the Cultural Revolution when he was persecuted heavily, so much so that he attempted suicide. Thankfully he survived, and once Mao had decided that Taijiquan was not a threat to the nation returned to teaching in the Chen village where he managed to tutor the next generation, who are all famous names in Chen style today. Without his efforts it’s unlikely that a martial tradition would have survived in the Chen village at all.

Collected Masterworks starts with two biographies of Chen Zhongshen, a famous fighter for hire from Chen village who lived during the tumultuous events of 19th century in China, suppressing rebels, and was renowned for his excellent martial skill. Longer versions of these biographies later appear in Chen Xin’s book. It feels somewhat like these biographies are added to the start of this volume to stake the claim of Chen fighters to being experienced fighters and serious martial artists.

Of more interest to the casual reader are the next two texts which are attributed to the famous Chen Chanxing (although the author notes they have also been attributed to Chen Wanting elsewhere), who was the teacher of Yang Luchan in most of the orthodox histories of Taijiquan. That makes them the most important texts in this collection. Mark gives excellent introductions to each text he translates, with copious notes.

The first text is “Chen Chanxing’s Verse of Taijiquan”. It’s short – just 1 page long – and although it doesn’t mention Taijiquan by name, reads like many old Chinese texts on Taijiquan. E.g.:

“Freely bending and extending, others know nothing, Always in contact, I totally rely on winding”.

The second text attributed to Chen Chanxing is a compilation of posture names from the Taijiquan form.

But the third and final text attributed to Chen Chanxing is where the mystery deepens. It is much longer and titled: “Chen Chanxing’s Discussion of Taijiquan’s 10 main points”.

Reading through the text of “10 important points”, I found the words eerily familiar, “in all matters separation must have unification”, “inside and outside are joined, front and back mutually support each other”…. then I realised that was because I was reading a modified version of the Xing Yi classics normally referred to as “The 10 thesis of Marshal Yue Fei” and sometimes attributed to the eponymous Song dynasty marshal.

You can read the 10 Thesis online here: https://ymaa.com/articles/2014/12/marshal-yue-feis-ten-important-theses-part-1

While they are of unknown provenance the 10 Thesis forms the basis for most of the classic writings on Xing Yi that you’ll find in later works; so I’d say its connection to the martial art Xing Yi is unequivocal.

Except here. Here, in Chen Zhaopi’s book it is presented as Chen Chanxing’s original writings on Taijiquan. The author (either Chanxing, Zhaopi, or maybe Mark Chen?) even puts the name “Taijiquan” into the text itself to make it seem more authentically about Taijiquan. E.g. “Taijiquan is ever changing. There must be energy everywhere…”

Obviously, these references to “Taijiquan” are not found in the other available translations of Yue Fei’s classic (the version linked above appears in “Xingyiquan: Theory, Applications, Fighting Tactics and Spirit” by Yang Jwing-Ming, for example). These translations use the term “martial arts” instead.

Not reading Chinese, I don’t know if the phrase “Taijiquan” was used in the original print edition by Zhaopi (1935), at a time when it was already in common usage, or was inserted into this translation by Mark Chen in this edition. And if it was used by Zhaopi, did he insert it or was it in the original source material allegedly from Chen Chanxing?

But either way, clearly something is being done to attach Chen Chanxing’s name to the history of Taijiquan by co-opting some old martial arts writings.

In the Translator’s Preference at the start, referring to the 10 points, Mark Chen writes:

“Interspersed amidst the theoretical discourse, the text contains perhaps some of the best practical martial-arts instruction ever written. It is clearly a transitional document on the timeline of taijiquan’s evolution, composed in an era when utility was still paramount – the work of a vastly experienced fighter wielding a vigorous rhetorical facility to convey the true “look and feel” of an advanced martial art. What emerges from the text is not theoretical pablum about soft overcoming hard, but a picture of the formidable fighiting system that made the Chen clan of Wen County some of the most feared caravan guards and bandit hunters of the Qing dynasty, from Hubei to Shandong.”

I’d say he’s right about the value of the text, and the reputation of the Chen clan, he just has the wrong author, and the wrong martial art!

Whether or not Marshal Yue Fei actually wrote these 10 thesis (obviously this is unprovable) is beside the point, the point is that they are well known and in wide circulation, and Chen Chanxing certainly did not write them. And yet this book treats them as the original writings of Chen Chanxing, without question.

Maybe I’m missing something here, (and somebody please correct me if I’m wrong) but I find this error perplexing as the author has clearly put huge amounts of effort into this translation, and agonises over each character he translates. The Appendices where he talks about the details of his translation and the provenance of different Taijiquan writings, like the Salt Shop Classics, and also the Chen Wanting origin story are really fascinating and show how much work he’s put into researching this book.

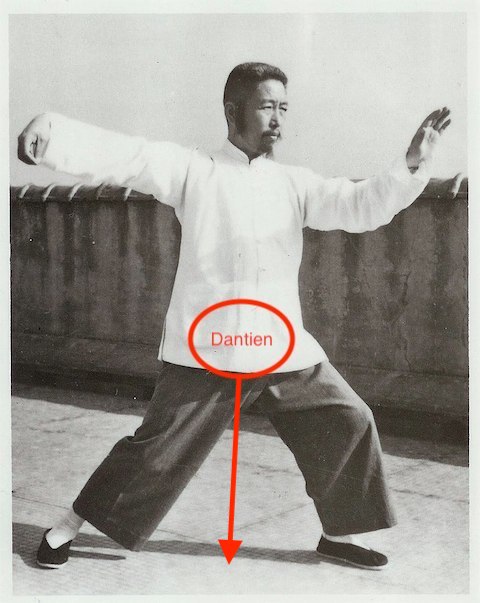

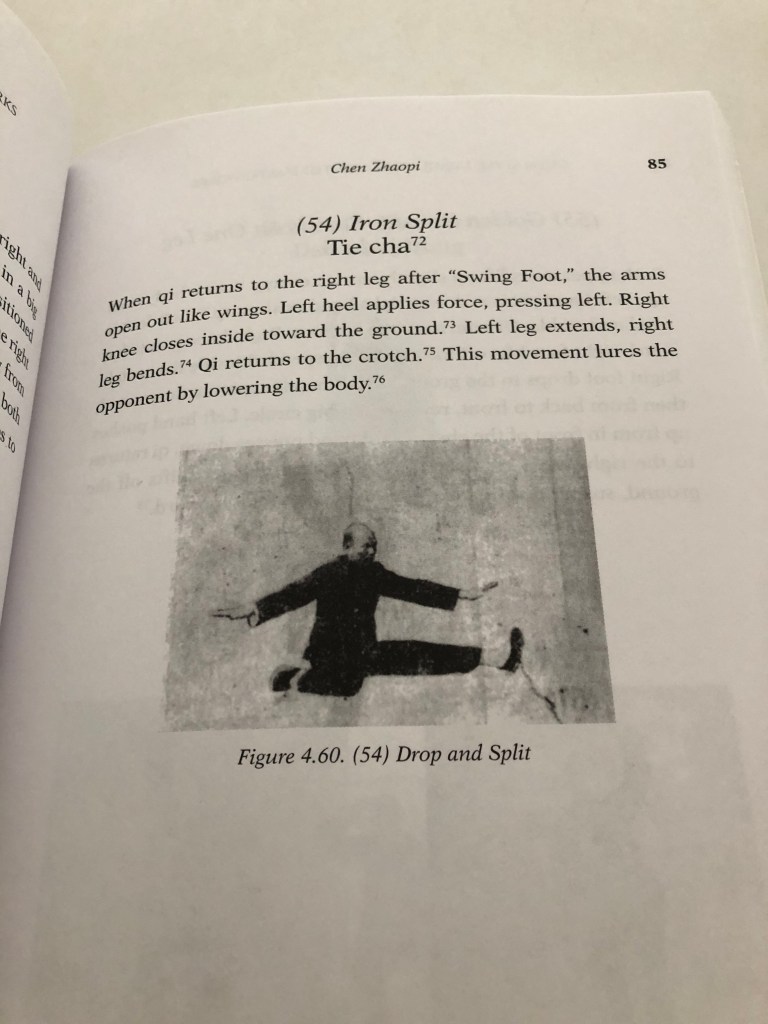

Moving on, the next chapter is by Chen Zhaopi himself and contains annotated photos of Zhaopi performing the Chen old frame first form. These photos will be of particular interest to modern day Chen practitioners as he performs many movements in quite acrobatic ways, including movement 54 called the “Iron split” where he drops to the floor in a dramatic half splits movement.

After this we have an explanation of push hands and the original texts written in Chinese. Finally, the appendices and copious notes sections are well worth reading.

Overall this book is an excellent addition to the literature on Taijiquan, and an essential purchase for all Chen stylists, although I keep coming back to the question of why Chen Zhaopi is presenting the Xing Yi classics as belonging to the Taijiquan literary canon and presenting them here as the writings of Chen Chanxing.

Chen Style Taijiquan Collected Masterworks is clearly a labour of love for the author and translator and every Taijiquan practitioner will enjoy it, but for me it ultimately throws up more questions than it answers.