Chen Taijiquan Illustrated is an exploration of pretty much everything that makes up Chen Taijiquan, from principles, and body methods to practical usage and philosophy. But the most notable thing about this Taijiquan book, and the place where we should probably start, are the illustrations, because they are what really separates this book from others of its ilk.

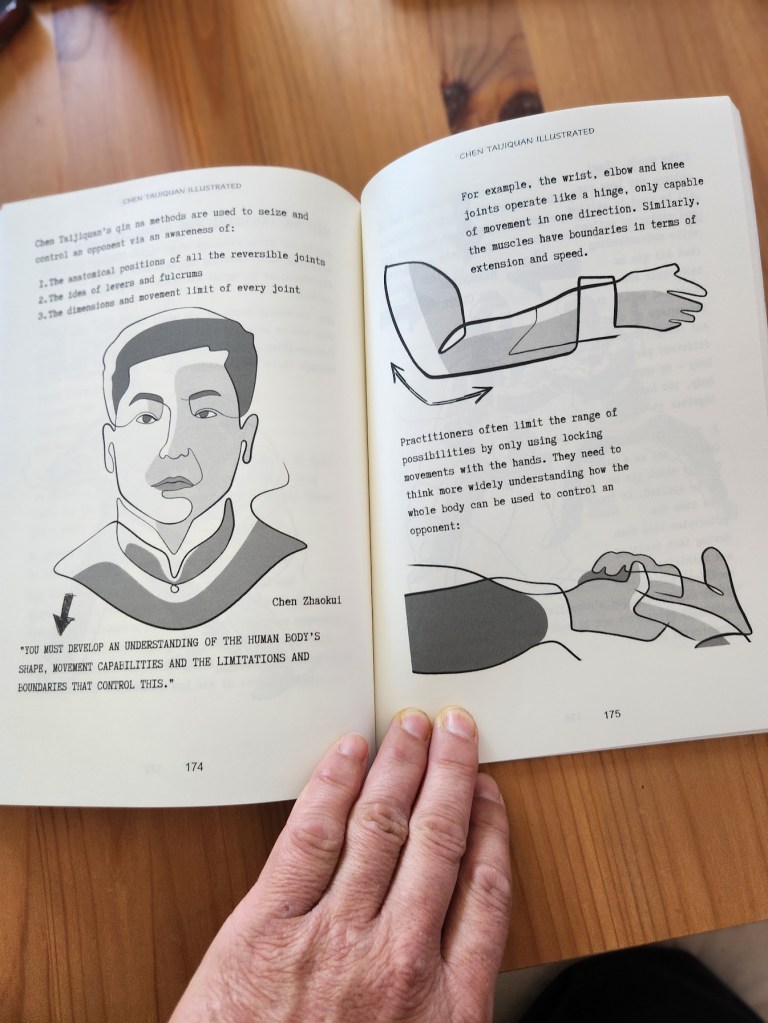

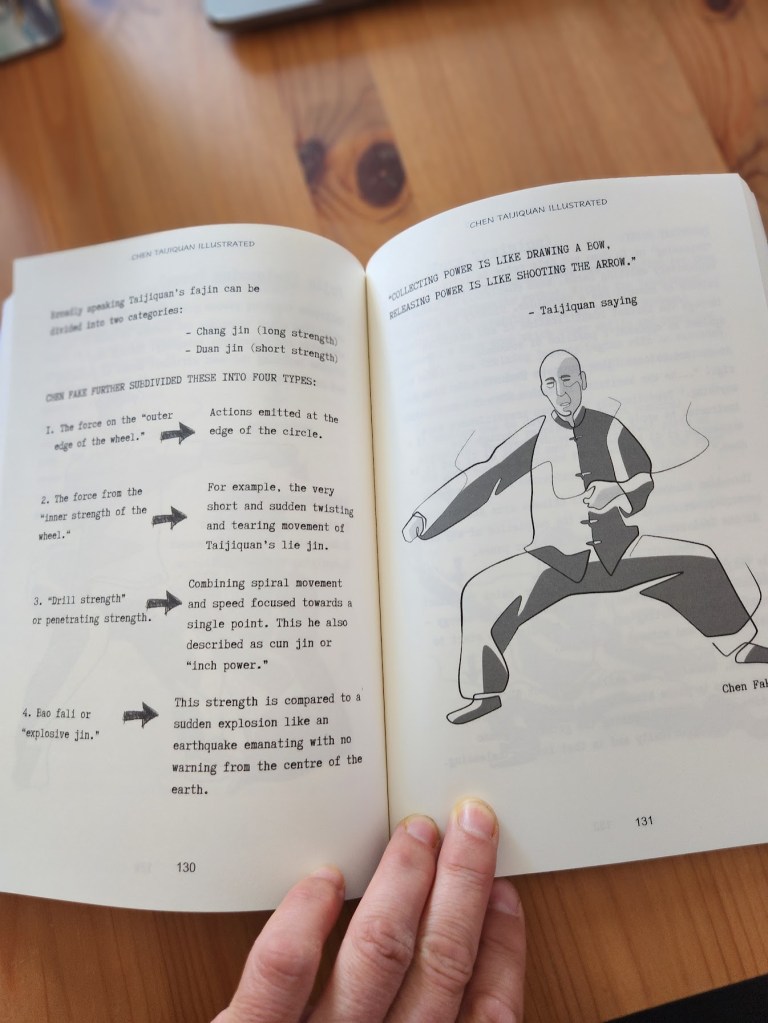

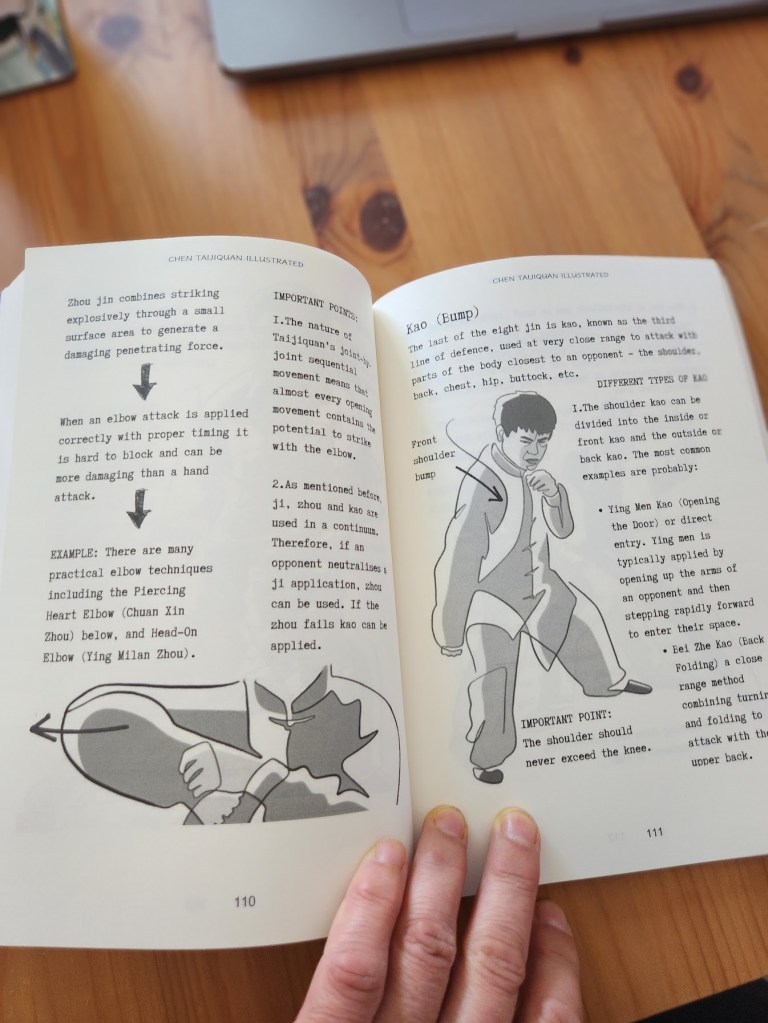

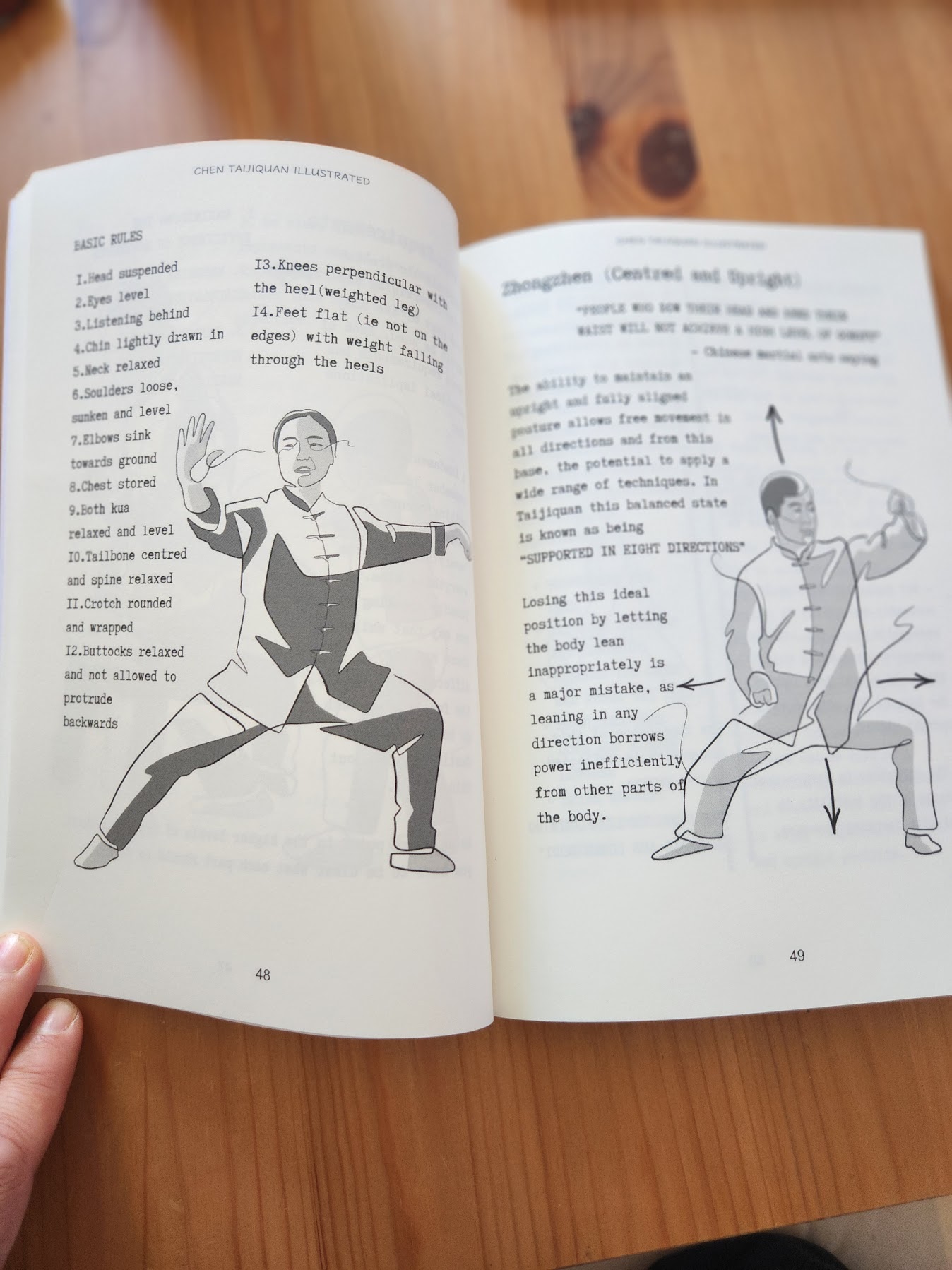

Almost every page here (and there are over 200) has some sort of detailed drawing on it that adds context to the text surrounding it. In fact, the whole book takes the form of a visual notebook, as if you are discovering a secret copy of the best-looking training notes you’ve ever seen. Surrounding the drawings are quotes from the most iconic practitioners in the Chen lineage, past and present, as well as explanations of principles, concepts and requirements of Taijiquan. Take a look and you’ll get the idea:

As you can see, the drawings are mainly done in a stylised cartoon way, which is actually very effective, and it’s pretty clear that these are photographs that have been traced over digitally, to produce the illustration, rather than drawn from scratch. The overall effect is really nice, and refreshingly modern and accessible.

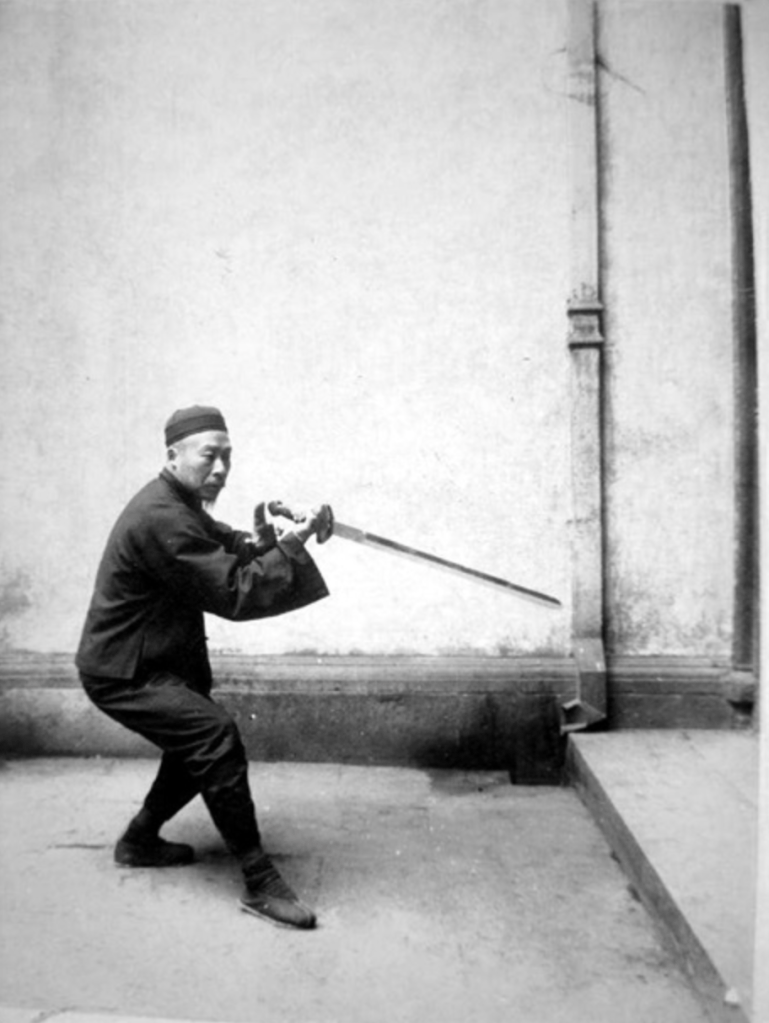

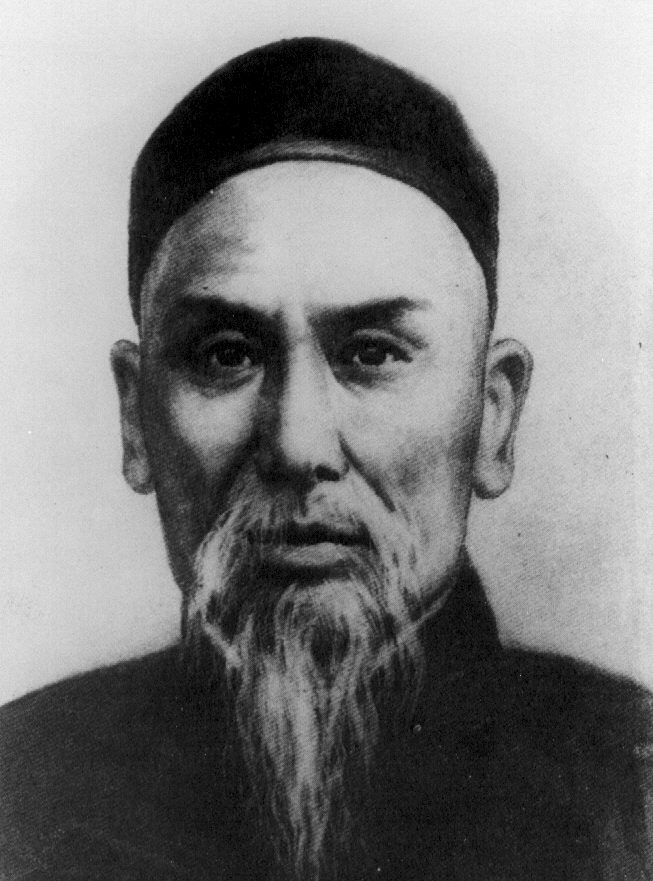

Because a Taiji master’s posture takes years to develop and is a reflection of their skill, you can learn quite a lot from just looking at it. So, having a drawing based on a real photo gives you the best of both worlds – you get to see the genuine skill of the practitioner on show mixed with the accessibility and visual appeal of an illustration.

In fact, in a lot of cases you can guess the famous master that the drawing is based on. For example, the book cover shows, I believe, a digital tracing of a photo of Chen Xiaoxing, brother of Chen Xiaowang.

It should be pointed out that not all the illustrations in the book are done to the same high standard, but there are only a few where the quality dips significantly.

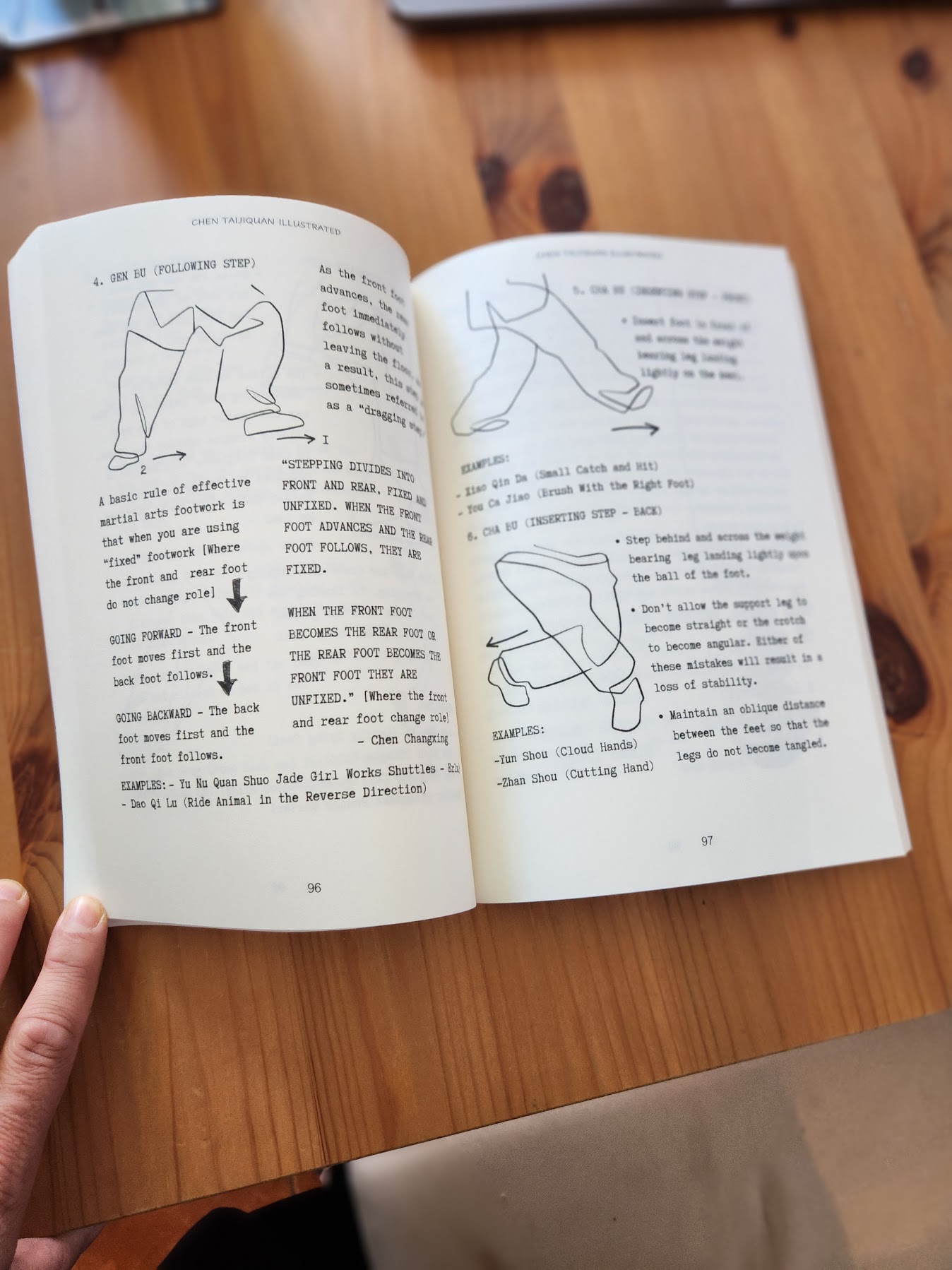

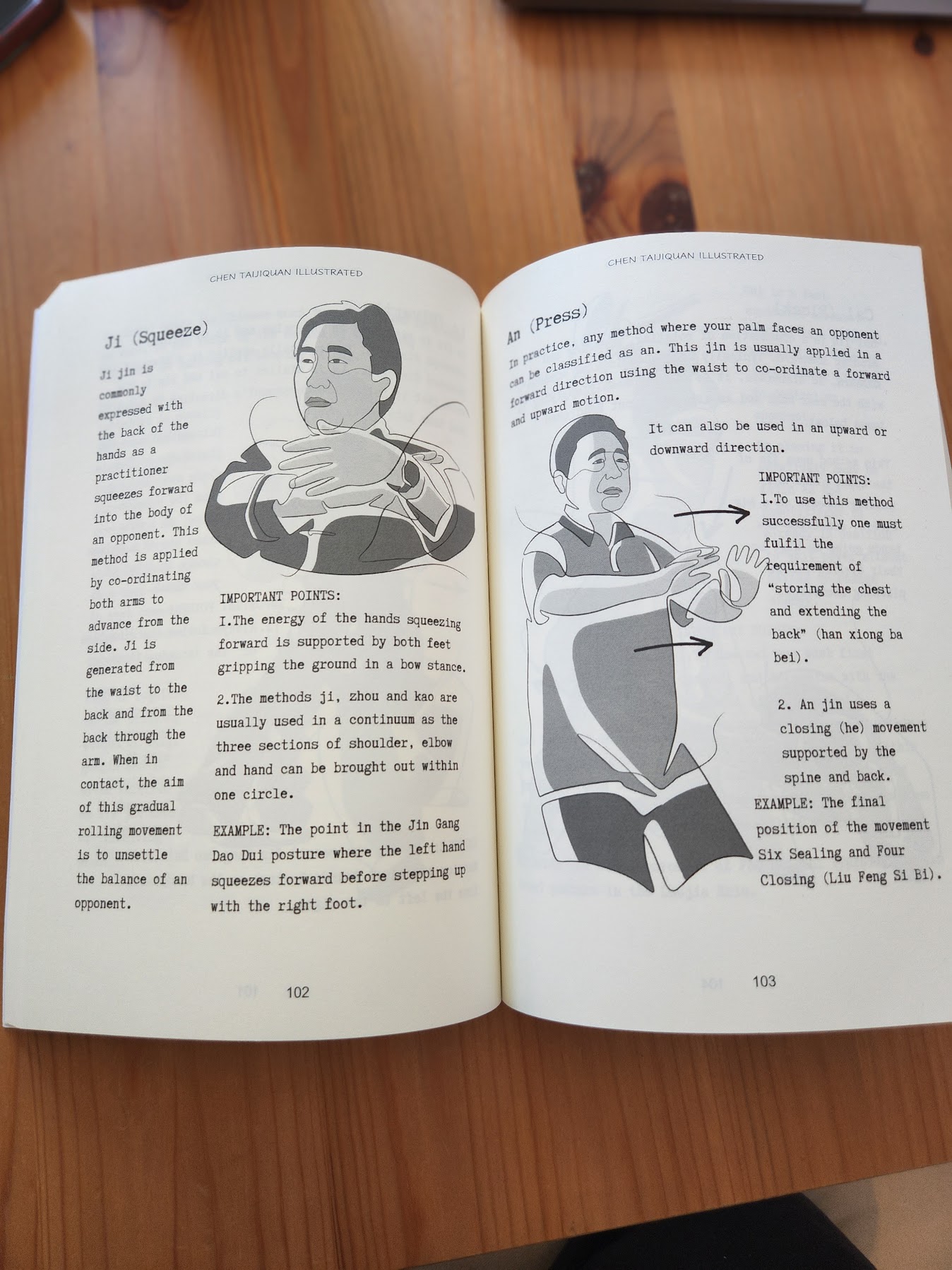

Chen Taijiquan Illustrated is split into three sections – Section 1, Body Rules (Shape and energy), Section 2, Practical use/Application and Section 3, Philosophical Roots. Section 3 on philosophy is tiny compared to the massive section two, which consists of a catalogue of pretty much all the practical methods found in Taijiquan – peng, lu, ji, an, listening, sticking, neutralising, push hands, hand methods, leg methods, stepping, chin na, etc. Pretty much everything to do with the Chen style is here!

The initial section on body requirements is very good, and something you can keep coming back to and the book goes into much more detail than you’d expect to find in a basic beginner’s book, which makes me happy. The explanations of the concepts and techniques in the second section can sometimes err towards being more of a catalogue of techniques than an in-depth ‘how to’ of each one, but there is always going to be a limit on how much can be achieved in print, and the illustration of various masters doing the method being discussed speaks volumes in itself, and adds a lot of depth. It’s also nice to see the martial methods of Taijiquan being discussed in detail, something that is also rare to find in a Taijiquan book.

Let’s talk for a moment about what the book doesn‘t include. For a start, there is no attempt to teach a form in this book, which is probably a good thing, as Chen style in particular would be hard to teach in a printed book due to its intricate nature and complex, spiraling movements. Also, there is no history section – personally I’m glad about that, as it’s a massive subject and would require too much space to do it justice, and frankly, it’s been done to death elsewhere, and matters not a jot to your actual practice of the art. If you want to discover the key to “internal movement” then you’ll find good pointers here, but if you really want to delve deeply into subjects like peng, groundpath and internal body mechanics then I’d say you should check out Ken Gullette’s book on the subject. Finally, there’s no mention of weapons here, which are obviously a huge part of the Chen art. The emphasis here is on body methods and bare hand methods only.

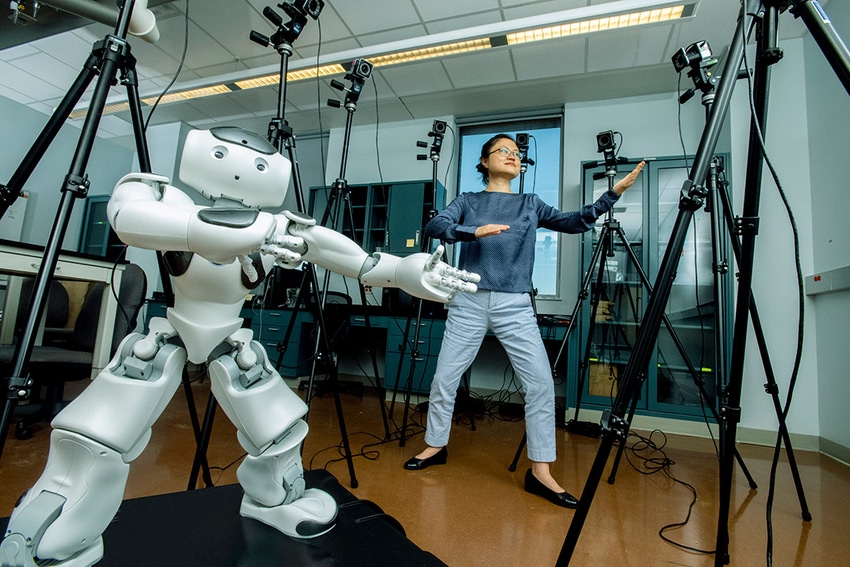

Taijiquan is a practical, doing art, not the sort of practice that benefits from too much intellectualism, and the visual nature of the book is great at reminding you of that fact, grounding the concepts and principles in practical reality.

Overall, I think this has to be one of my favourite books on Taijiquan ever produced. This is really one of the most comprehensive collection of training notes you’ll ever come across. And because everything is fitted around pictures, there are no long, boring, passages of text, meaning you can dip in and out at any point. In fact, just picking it up, flicking to a random page and starting to read for a few minutes can easily give you inspiration for your practice that day.

Highly recommended, and while obviously best suited to Chen style practitioners (there’s a lot of discussion of silk reeling), I think a Taijiquan practitioner of any style would get a lot out of it. I certainly did.