I had the good fortune to guide a group of people through some Xing Yi Monkey recently, which made me focus on it more and practice it a bit harder in the run up, which was a good thing. (I’m also available for children’s parties and Hen parties too, btw). Anyway, I wrote some notes about it, which I’ve typed up below.

A unique animal

When it comes to the animals in the natural world that we can look at for inspiration for martial methods the most obvious place to start is with one of our closes cousins, the primates. Like us, monkeys can stand upright, if only for short periods in some cases, they have hands that can grip and even a bit of limited tool usage. However, monkey is not a good place to start your journey into the 12 animals of Xing Yi.

The first thing to realise about monkey is that it breaks a lot of the ‘rules’ of Xing Yi Quan, which is one of the reason why it’s often taught last amongst the 12 animals. My teacher taught the animals as almost self-contained mini martial arts – each one had a different strategy and techniques, but Monkey wins the award for being the most unique amongst them. It really does stand up on its own as a complete martial art.

Almost all of the rest of Xing Yi Quan can be performed in formation, standing in a line with other people, since you generally move forward and backwards along a straight line (except for the turns, obviously). Whether this really harks back to an ancient heritage of soldiers moving in formation is speculation of course, but it should be noted that a row of people holding a spear and standing side by side can perform the 5 elements and most of the first 11 animal links while all facing in the same direction without impending each other, provided they all turn at the same time. That’s possibly one reason why Xing Yi is so obsessed with keeping the elbows near the ribs.

But Monkey doesn’t follow these rules – it’s breaks the line. Or more accurately, it’s what you do when the line has been broken. Attacks in monkey are reacted to and defended at diagonal angles – there’s footwork you don’t find in the rest of Xing Yi and there are changes in tempo, bursts of speed and jumping. It’s as if your nice orderly line of soldiers has been broken up and the battle has become more of a melee situation.

All the different types of monkey have similar movement, but the monkey native to China that Xing Yi is probably using for inspiration is the Golden Monkey. And thanks to the BBC there are plenty of Golden Monkey clips available to watch – this one of two tribes coming together and fighting over resources is particularly good:

And here’s an interesting clip of a group of wild monkeys who have learned to trust humans for food:

Both clips are a gold mine of information about how these animals move.

Monkey Pi

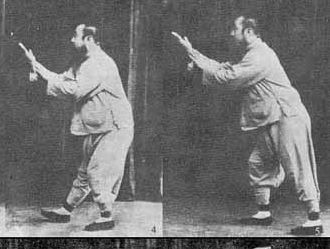

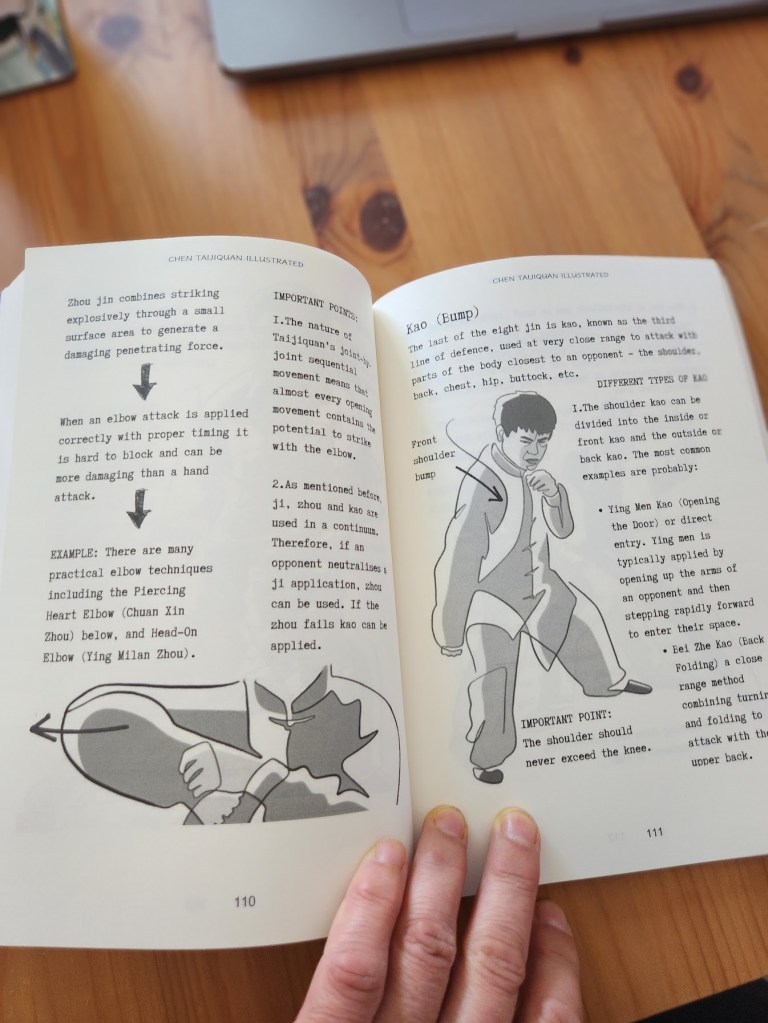

Pi (splitting) is the main energy from the 5 elements that is used in monkey, but while in Pi Quan the arm uses the elbow joint as a pivot point for delivering the downward chopping strike (a bit like the swing of an axe), in monkey it’s the wrist that is the pivot point. The monkey Pi is more like a slap, but don’t think that makes it ineffectual. A relaxed and loose slap delivered using good body mechanics to the head can easily result in concussions.

Monkey also tends to eschew single strikes – everything is done in quick flurries of 3. This is called a triple palm. Often the first strike is to open up their guard, or intercept a strike, the second is to hit the head, and the third can be done as a grab and pull on their limb or head, leading to your own head butt or knee strike – an action called ‘wrapping’. The back of the hand can also be used as an upward deflection to the opponents arms, for when the monkey wants to enter deep.

Range

Talking of entering deep, Monkey wants to either be too far away for you to hit (beyond kicking range), or right in at what would normally be called grappling range, (i.e. too close for what is generally called striking range) but the use of close body palm strikes delivered by turning the body sharply and the cross stepping opens it up as a striking range too.

Take a look at this video of a monkey antagonising a Tiger cub (I don’t think he’d be brave enough to try this on a fully grown tiger!) to get the idea of range:

As you can see, monkey is something of a trickster engaged in a war of attrition. A tiger generally wants to finish the prey in one big action, monkey will keep attacking, wearing it down over time. Often the monkey’s goal is simply to drive the opponent away out of its territory.

Agility, but with stability

Obviously to close the distance from outside kicking range to inside punching range you need tremendous agility to play monkey, however, agility without stability is a recipe for disaster, which is another reason for teaching monkey last – it requires a very solid understanding of the footwork methods of Xing Yi Quan. It uses a cross step frequently, and also spins and jumps.

Monkey requires you to be agile, but rooted when you step. Without that combination the movements of monkey can become just a dance. The stability also relates to being relaxed in your movements. Because monkey movements tend to be done fast the tendency is to get tighter and more tense as you do them. I find consciously trying to relax while doing monkey is required more so than in other Xing Yi animals.

Tea cups exercise

The arm methods of money require more utilisation of the joints of the wrist, elbow and shoulder than the other methods of Xing Yi. Techniques like “Reach around the back of the helmet” require significant mobility of the arm joints. The best way to achieve this is to become adept at the famous tea cups exercise. You should practice this is with actual tea cups full of tea (or water) and try not to spill any. This is incredibly difficult!

Here’s a basic instructional on the tea cups exercise:

Yin and Yang

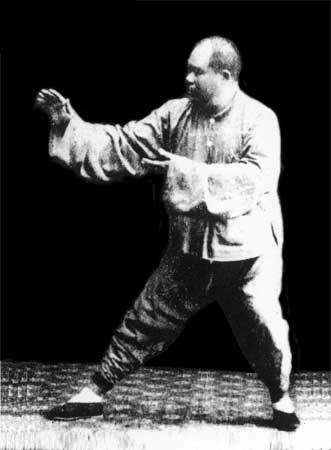

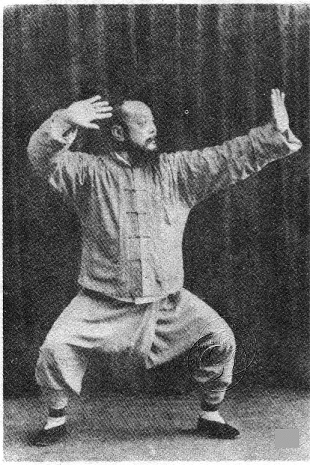

Finally, we do a Yin and a Yang monkey in our Xing Yi – the Yang monkey is the bright, lively, younger monkey, while the Yin monkey is the more older experienced monkey who uses heavier techniques. Almost all the video you see of Xing Yi money on the Internet are showing the Yang version. The most famous move from Yang monkey is the upward ‘flying’ knee strike. Here’s a good example:

To be honest, I haven’t seen any other Xing Yi group do a Yin monkey like we do, but here’s a little clip of me doing some Yin monkey so you can see what I mean:

You might also like to read my previous post on the Heretical Baguazhang and Xing Yi Monkey connection and also episode 65 of the Heretics podcast.