Let’s get this thing moving!

It’s pretty well established now that you need to ‘move from the centre’ in Tai Chi – (or ‘center’ if you’re American). But what is the centre?

In the ‘internal’ model of moving the body in Chinese martial arts, the centre is expressed as the ‘Dan Tien’, the point roughly an inch below the navel and 2 inches in from the surface. This is where you put your mental focus to move your body from. So, rather than the arm movements coming from the shoulders they come from the torso, which is turned by moving the waist, which is, in turn, powered by moving the dantien. So it all works together, but with the movement coming from the dantien.

The problem with moving from the centre like this is that you can do it roughly correctly and your movements will still be flat (for want of a better word) and lacking power. Sadly, most of the Tai Chi you see demonstrated is like this. I could post a video, but it would seem like picking on somebody, so I won’t – but just search YouTube for Tai Chi videos and ask yourself if they look powerful or not. It’s far too easy to have the dantien ‘floating’ on top of the hips, so that the legs are just propping it up, rather than being involved. To make the movements truly powerful you need to get the legs involved.

As it says in the classics, the jin (power) should be…

“rooted in the feet,

generated from the legs,

controlled by the waist, and

manifested through the fingers.”

If you imagine a triangle drawn from the two feet up to the dantien, that’s the power source of Tai Chi. So, as the dantien turns, so the legs need to spiral in and out to help support the movement and transfer this spiral force to the rest of the body.

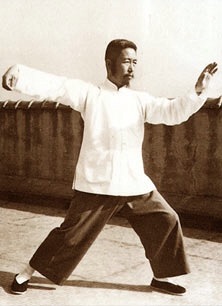

Chen Xiao Wang explains it very well in this video. After talking about the legs and rotating dantien he goes on to talk a lot about Qi and Yin and Yang, which can be confusing, but just concentrate on what he says at the start for now about the legs working with the dantien to power the arms.

Of course, there’s more to it, which he goes on to discuss, but that’s for another time.