Thanks to Full Contact Way for mentioning The Tai Chi Notebook in its Top 40 Blogs to help you with your martial training. There are plenty of good reads there if you’re looking for inspiration.

Tai Chi applications

Fist Under Elbow, and natural posture

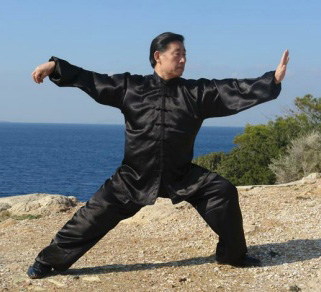

Here I want to discuss what a natural posture means in Tai Chi Chuan. I was working on the posture we call ‘Fist under elbow’ with a student today. The posture looks like this:

Fist under elbow – Yang Cheng-Fu

The word translated as ‘fist’ could also mean ‘punch’, so you could equally call the posture, ‘Punch under elbow’. It looks a bit like the Judo Chop I talked about recently, but it’s not done like that at all in application. Instead of a chopping, downward, movement it’s a forward and outwards, palm strike done with the left hand. You can see this immediately when you see it done in motion. Here’s Yang Jun, the grandson of Yang Cheng-Fu who is pictured above, teaching the movement in his family’s style of Tai Chi.

You might ask why your other hand is punching under the elbow. I was always taught this was a hidden technique, where you’d turn the left hand into a deflection of the opponent’s attack and punch them with your right, but in the Tai Chi form it wasn’t show explicitly, and the punch was hidden away under the elbow… In application, it looked a lot like a little bit of Wing Chun Kung Fu.

I always have doubts about the validity of these sorts of explanations though. Firstly, I don’t know why you’d want to hide a technique like this? Who are you hiding it from, and why? And it’s not an especially deadly technique, so it’s not like it is dangerous for people to see it. There are much more dangerous techniques shown openly in the form. And secondly, if you don’t actually practice it then you’ll never actually be able to do it under pressure, so hiding things away is not an ideal practice method.

I think it’s much more likely that the posture itself has special cultural significance (as say, part of a religious ritual, or maybe it relates to Chinese cosmology), so was included in the Tai Chi form sequence, or perhaps it’s something of a signature move that was handed down over the generations from an older martial art, and has lost its original meaning, but remained as a kind of nod of respect to the forefathers.

Either way, it’s in the Tai Chi form now, and shows no sign of being removed, so we might as well get on with learning it properly.

My point in writing this article was that I find students generally don’t perform this posture particularly well. Perhaps it’s something to do with the arm position being slightly uncomfortable unless you can relax sufficiently, but it seems particularly suited to making mistakes. Maybe it’s because it looks a bit like an “on guard!” posture, but if you ask a student to take up this posture they will invariably hunch the shoulders, or make their leading arm too stiff and aggressive, or get the angle of the hand and fingers all wrong.

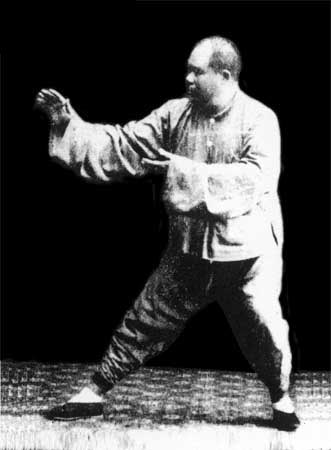

Here’s an example of what I mean. Look at how tense this guy’s arms are:

He’s holding up his right elbow instead of letting it drop. His left arm is almost locked straight and both arms are too high: Instead of ‘sinking the chi’ he’s letting it rise up, which makes him unsteady.

In Tai Chi the shoulders should naturally round and the elbows should drop – this makes your posture softer and more relaxed – ‘sung‘, as we say in Tai Chi.

If I was to walk up to the person above practicing on the beach and at the moment they formed their Fist Under Elbow I was to slap their arm away at the elbow then the chances are that I’d severely compromise their structure and balance, possibly knocking them over, giving me ample room to attack.

In comparison, if you look at the picture of Yang Cheng-Fu above again, then you can see he is much more relaxed and comfortable in his stance. You get the feeling that if you tried to slap his arm away he’d be able to just let his arm go with your motion, and let it swing back around and slap you in the face! (This was exactly what happened to me the first time I got hands-on with my Tai Chi teacher, so I can talk from experience!)

Yang Cheng-Fu’s more natural posture means that his centre of gravity is within himself in the area of the dantien. And because mind and body are linked, it’s more likely that his mind is focussed and aware of what’s happening. Once your physical centre of gravity starts to shift out of your base, so too does your mental focus. And equally, if your mind is all over the place when you’re doing your Tai Chi form then, more than likely, your physical balance will suffer for it.

In an ‘internal’ martial art we try to harmonise what’s happening between the external and the internal parts of the body. That’s what I’m trying to do in each posture of the Tai Chi form – become more centred,both mentally and physically. I want to have a more natural body that is free from artificial posturing. Postures that look ‘held up’, as if from invisible wires from the ceiling, are not as useful for combat as natural, rooted, aware postures that can meet the demands of the moment.

(A quick tip for getting a more natural posture is to take up a posture from the Tai Chi form, put your arms in what you think is the correct position, then take a big breath in, all the way up to your shoulders then let it all out in one big gasp. Let your arms settle to where they need to be, rather than holding them up. That relaxed, sunk, posture you now have is what you should be looking for in Tai Chi Chuan.)

As it says in the Tai Chi Classics:

“The postures should be without defect,

without hollows or projections from the proper alignment;”

“Stand like a perfectly balanced scale and

move like a turning wheel.”

“The upright body must be stable and comfortable

to be able to sustain an attack from any of the eight directions.”

Doing Tai Chi right -the road less travelled

A Tai Chi Chuan performer dong a form, as viewed by an observer, is not in a binary right/wrong state. If it were then everyone would be ‘wrong’ because Tai Chi is that point of perfection that everybody is striving towards. I’m not talking about superficial things that form competitions are judged on, like the wrong height for an arm, or the wrong length of stance. I’m talking about maintaining a perfect state of equilibrium (yin/yang balance) throughout the movement. Constantly going from open to close in perfect harmony. Even the best experts are making little errors constantly as they perform a Tai Chi Chuan form, they’re just so much better than the average person that we can’t see or appreciate them.

But equally, all roads to not lead to Rome. Not everyone doing Tai Chi is on the right track. There are so many side roads you can wander off on, especially with so many other tempting martial arts available on the high street that are a bit like it, but not the thing itself.

There’s one particular side road I want to discuss here that is so close to Tai Chi, but also, so far from it, that you’ll never get there if you go too far down it.

“a hair’s breath and heaven and earth are set apart.”

One thing you’ll find a lot of people, particularly instructors who are into the martial side of Tai Chi, doing is putting their weight into things, rather than moving from the dantien.

So what do I mean? Well, think of it like this: if somebody is doing a Tai Chi form and each time they lift and arm they keep their body relaxed and let their body weight fall into the arm they can generate a significant amount of power, while appearing to remain relaxed – all the things Tai Chi is supposed to be.

It’s impressive, and will convince a lot of people of your awesome martial prowess, but it’s not really how Tai Chi is supposed to work. If you’re committing your weight into a technique then you get a lot of power, but you also get a lot of commitment. As an analogy, it’s rather like swinging a lead pipe to hit somebody. If you make contact then fine, you’ll do a lot of damage, but if you swing and miss then you can’t change and adapt quickly enough to deal with the opponent’s counter.

In contrast Tai Chi is supposed to work like a sharp knife – you can generate power without committing your weight into the technique, so you can change and adapt, just as if you were switching cuts with a blade. The knife is so sharp it doesn’t need a lot of weight behind it.

To get this curious mix of non-committed movement and power you need to move from the dantien. This requires a co-ordinated, relaxed body, that’s driven from the central point. This type of movement really does involve re-learning how to move and is developed in things like silk reeling exercises and form practice.

Learning to put your body weight into techniques is comparatively much easier to grasp, and may even be a useful first step, but it should never become the goal of your practice. It’s only when you come up against somebody well trained in dantien usage that you realise the inferiority of other methods.

Dr Who Single Whip

Good to see the Doctor’s Tai Chi is on point.

My friend Cavan Scott writes Dr Who comics for a living. Great to see that his latest Doctor Who: Supremacy of the Cyberman has a nice bit of Tai Chi on the cover!

Chen Xiao Wang approves.

Two points on a circle

Let’s look at how moving in a circular way can produce effortless power.

If you rotate a circle then different parts on the circumference will move in different directions relative to each other. This is crucial to the art of Tai Chi Chuan. Let me explain.

This video of rollback from Yang style is very nicely done. Although I don’t speak Chinese, so I have no idea what he’s saying, the application is nicely shown and very clear.

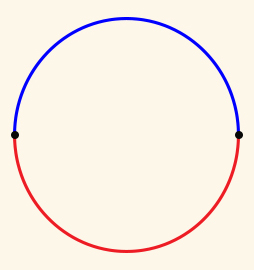

Let’s take a circle.

Notice that the two points in black on the outside that are directly opposite each other.

If you rotate the circle clockwise, or anti clockwise, then the two points will rotate relative to each other. And from the perspective of the centre of the circle, they will be moving in opposite directions.

Now, if you imagine the circle is the view of a Tai Chi practitioner in the video of rollback, but viewed from above, you can see that if they rotate around their centre then the parts of the body on the opposite sides of their circle will be moving in opposite directions.

Now, unless they are spinning constantly, they won’t keep this up for long in the same direction, but it will be happening continually throughout a Tai Chi form, just in different directions and with different parts of the body.

So, while his left hand is rotating backwards to the left, clockwise direction, his right shoulder is moving equally forward to the right, still clockwise. They are the points on opposite sides of the circle. Obviously he then hits the limit of his rotational possibilities (without stepping) and stops.

Obviously Tai Chi is more of a sphere than a flat 2D circle, but hopefully the point stands and shows how circular movement around the centre point can produce power from the whole body.

Cracking the Code: Tai Chi as Enlightenment Theatre

Scott Park Phillips’s much anticipated film about the connection between Tai Chi and Chinese Ritual Theatre is finally here.

I met Scott last year, when he introduced me to his theory of Tai Chi as Ritual Theatre for the first time. His ideas were so ‘out there’ compared to the usual history of Tai Chi that I’d encountered, and his presentation so enthusiastic, that I found both him and his ideas fascinating, and I think you will too. As well as being a historian, he’s a performer and entertainer (and third-wave coffee drinker). He presents his ideas as such. I’ll never forget him spontaneously standing up in the pub and demoing his Chen style form walkthrough (during which he explained his Theatrical interpretation of the postures) for me, and the rest of the pub, whether they wanted it or not! 🙂

It’s hard to grasp these ideas in the written word, so I asked him at the time if he could put down his Chen style walkthrough, on video and he said he was already working on it. Well, it turns out he was, and he’s finished the video project! Here it is:

The video is professionally produced and does a good job of presenting his ideas (although I’d have liked some parts to be a little slower, as there’s so much to absorb). The parts about the Boxer Rebellion I found particularly interesting, for example.

I’ll leave you to decide what you think about his ideas, but personally I think he’s onto something, and (importantly) I don’t think we need to be threatened by these ideas as somehow undermining the seriousness or effectiveness of Tai Chi as either a martial art, a health-giving art, or as a vehicle for delivering internal power.

I can see how some will think that it detracts from the effectiveness of the art we have today, with retorts like, “I don’t practice a dance!” or “I’m not doing a ritual!”

I raised this issue with Scott myself, and his response was along the lines of ‘If you’re a serious martial artists who practices Tai Chi (that puts you in the 0.00004% of practitioners!) then I’d say it doesn’t matter – a skilled martial artists can use anything to make good training out of’. That’s not a direct quote, I’m paraphrasing from memory here. But logically I think he’s right – I don’t think it makes Tai Chi any less martial or any less effective if the ‘form’ that is being used as a vehicle to deliver Six Harmonies movement (to borrow Mike Sigman’s nomenclature) originally came from a theatrical ritual. Also, in the west we have a different association of the words ‘theatre’ than they do in China, where ‘theatre’ always had much more of a religious element. Everything arrises out of a culture, so it’s interesting to look back at the culture that Tai Chi arose out of. Academically there are already several good theories for why the Taoist Chanseng Feng always gets associated with the history of Tai Chi, from politics to spirituality, and Scott’s theory is just another to add to the pile. If you don’t want to add it to your pile, then don’t.

Remember, looking back into the murky origins of Tai Chi isn’t relevant to your actual practice today, or the subsequent direction Taijiquan went in, just keep on doing your thing. If you’re using Tai Chi form to practice fighting applications, or silk reeling, or to clear your meridians, etc, then you’re still doing just that.

For more information on Scott check out his weakness with a butterfly half step twist martial arts blog (or whatever it’s called these days), and he’ll be in the UK giving a lecture at the second Marital Arts Studies Conference in July, which I’m hoping to attend.

Enjoy!

Wave hands like clouds

A look at the Cloud Hands movement of Tai Chi, and what it’s really all about

Cloud hands, or ‘wave hands like clouds’ as it’s also known, is one of those classic Tai Chi movements that characterise the art. It’s done in slightly different ways in different Tai Chi styles. Take a look at the variations:

Master Yang Jun, (Yang Cheng Fu, Yang style):

Master Chen Zhen Lei, (Chen style):

Master Sun Ping, (Sun style):

I’m not comparing myself to the masters above, but here’s a GIF of me doing it, since I have that on video I might was well add it to this post:

Me: (Old yang, also called Gu style)

As you can see, the Yang style is more of a vertical arm block, the Chen style is more of a horizontal elbow strike while the Sun style has the palms facing outwards. It’s a case of different horses for different courses, but while there are subtle differences between them, they all involve the common theme of stepping to the side while rotating the arms in circular motions (presumably like clouds on a windy day).

Martially speaking, I think of this movement as intercepting an opponent’s strike and throwing the attacker out, or applying a lock to their arm through the action of turning your waist. To the attacker it should feel like they’re putting their hand into a blender – it gets caught up and crushed and it shouldn’t feel easy to retract your arm once it’s trapped.

It’s easy for beginners to make the arms ‘flat’ in this posture – instead they need to be continually projecting outwards. I think of them as being like the antlers of a stag, or the branches of a tree – they grow outwards, and are slightly curved. If you’re going to intercept your opponents strike with this technique, then it’s going to help ‘catch’ their attack if the intent in your arms (your antlers) is to project outwards.

The real lesson of Cloud hands though is to turn the waist. It’s a common mistake to not turn the waist enough in Tai Chi, and I find that, for the beginning student, a breakthrough in this area often only comes about through a study of Cloud Hands as an isolated technique, repeated over and over. Notice that if you removed the stepping from Cloud Hands then it wouldn’t be a million miles away from the stationary silk-reeling exercises that go along with Tai Chi, with one hand performing a clockwise circle and the other an anticlockwise circle. Indeed, performing Cloud Hands repeatedly can serve a similar function to basic Silk Reeling exercises.

As it says in the Tai Chi classics, the body should be directed by the waist at all times, so as you turn from side to side in Cloud Hands (let’s not worry about the stepping for now) your arms should only be moving because your waist is moving. If your waist stops, then your arms should stop too. This especially applies at the crossover points, when you’ve turned all the way to the side and the arms swap position, so that the lower one becomes the upper one, and vice versa. This is the point that beginners usually drop the principle and use some isolated arm movement, instead of keeping it all coming from the waist. It’s usually a revelation to the student here that you need to turn the waist a little more than you think you do to keep it as the commander of the movement – you should feel this using muscles in your lower back you normally don’t reach.

Remember, in Tai Chi you’re looking to continually maintain a connection (a slight pull) from the toes to the fingers, with movement directed by the dantien like the spider at the centre of a web. If you keep this connection (or slight tension) and the waist control at these crucial crossover points in Cloud Hands then you’ll be well on your way to keeping it throughout your whole form performance.

Don’t push the river, listen to it instead

Bruce Lee was onto something with his water analogies…

I recently read the phrase, “Don’t push the river, listen to it instead”, and it resonated deeply with me because it’s a great way of summing up my approach to jiujitsu’s rolling and tai chi’s push hands. The water analogy was famously used by Bruce Lee and also crops up a lot in the Tai Chi classics, for example “Chang Ch’uan [Long Boxing] is like a great river rolling on unceasingly.”

The flow of water is analogous to the flow of energy, or movement, when performing a Tai Chi form, or between two people engaged in a martial activity . In both jiujitsu and tai chi your ultimate goal is to ‘go with’ this flow in such a way that you come out on top. You want the opponent to be undone by their own actions.

In jiujitsu that might mean not using excessive strength to press home a collar choke from mount if your partner is defending it well, and switching to an armbar instead, then switching back to the collar choke (and hopefully getting it) when they defend the armbar.

In push hands it could mean not resisting your partner’s push and using Lu to let it pass you by, then switching to an armbar to capitalise on their over extension.

Of course, this is for when you’re engaged in the ‘play’ mode of both these arts, which is the mental space you need to occupy if you want to get better at either of them. This is the relaxed practice that nourishes the soul. It kind of goes without saying that in competition or in a self defence situation you’d be better off in Smash Mode. But when winning isn’t the only thing that’s important you need to open up your game a little and keep it playful. Or ‘listen to the river’ as the phrase has it. It takes a lot of expertise to be able to be that relaxed in a real situation, but as your experience in the art increase so too should your ability to remain relaxed under increasing amounts of pressure.

Rickson Gracie said, ‘you can’t control the ocean but you can learn to surf’ and that’s the heart of what I’m talking about.

To be aware of the way the river is flowing, and not waste futile energy pushing it in a direction it doesn’t want to go you need a degree of self awareness, and the ability to be aware of the situation you are in. And to get that you need to slow down and stay calm. Or, as the ancient Taoists said:

“Do you have the patience to wait

Till your mind settles and the water is clear?

Can you remain unmoving

Till the right action arises by itself?”

Lau Tzu, Tao-te-Ching

Rollback – the unfinished technique

Here’s the best thing to do after you’ve applied Tai Chi’s rollback.

One of the things that comes up a lot in Tai Chi push hands training that’s geared towards the martial side of Tai Chi is what to do with the opponent after you’ve done Rollback. Rollback uses Lu energy to lead the opponent in and control them, with their arm kind of locked, but not to the point where they’d tap. In the Yang form there’s no ‘finish’ from this position – after controlling them you strike with Press (Ji). This is ok, but to me it seems like you’re giving up the advantage you have over them because of the control that rollback affords in exchange for a quick strike. It looks like this:

There are several alternative things you can do – turn it into a push away (into a wall?), turn it into a takedown where you keep the pressure on the arm and shoulder, forcing them into the ground, or you can go for my preferred answer, which is to turn it into a standing arm bar as shown in this video:

Key things to note:

1. He puts his elbow over the top of their arm and makes sure the locked arm is snug in his armpit.

2. On the locked arm the little finger edge is pointing to the sky.

3. In the finish position he rotates his wrists around the opponent’s wrist so that both his thumbs point upwards – this gives you maximum leverage on the arm.

4. Once the opponent is controlled you can look around and watch out for further danger from somebody else.

I like this solution because it’s a really powerful arm lock and you can move into it from the end of the Tai Chi rollback posture fairly easily. You can feel it would be easy to break the arm from here, and the opponent is pretty much helpless. Obviously, in a self defence situation the level of force you exert needs to match the severity of the threat you feel you are under, so don’t go breaking the arm of people who have innocently patted you on the back, and also take care of your training partners. Don’t break your toys!

Brothers in arms – Rickson Gracie and Tai Chi

A discussion of the similarities between BJJ and Tai Chi

So, finally, here’s my much delayed look at the similarities between BJJ and Tai Chi. This is probably an impossible topic to give justice to fully, but I’ve given it a go and hopefully my perspective will be useful to others. I’ve already attempted to define Tai Chi in a previous post, so the next logical question is, ‘what is Brazilian JiuJitsu?’ Well, explaining what the art is, how it evolved and where it came from is not a simple job but luckily a lot of people have made a lot of (very long) documentaries that explain the whole story of the Gracie family, the in-fighting, the out-fighting and everything else in-between, so you’re better off watching those than having me explain it all again here. If you don’t fancy watching them all then the (very) short version is “it’s an off-shoot of Judo that has more emphasis on ground fighting”.

Try these for size:

The Gracie Brothers and the birth of Vale Tudo in Brazil:

If you want to find out how the art evolved once it entered the United States, and how it compliments other grapplings arts, then check out Chris Haueter’s incredibly entertaining speech at BJJ Globetrotters USA camp:

And finally, don’t miss the excellent Roll documentary on the spread of BJJ in California:

Fighting fire with water

But my concern here is not really the history of the art. I’m more interested in the technical similarities between Tai Chi and BJJ. I’ve heard Brazilian JiuJitsu described as being “like Tai Chi, but on the ground”. I understand where people coming from with that sentiment, but I can’t quite go down that route myself, or rather, I’d settle for saying that it is like Tai Chi, but also explicitly not the same. The one central idea that both BJJ and Tai Chi share is that it’s smarter to not oppose force with force, and instead “yield to overcome” (from a Tai Chi perspective) or “use leverage”, from a JiuJitsu perspective.

As it says in the Tai Chi classic “Treaste on Tai Chi Chuan”:

“There are many boxing arts.

Although they use different forms,

for the most part they don’t go beyond

the strong dominating the weak,

and the slow resigning to the swift.The strong defeating the weak

and the slow hands ceding to the swift hands

are all the results of natural abilities

and not of well-trained techniques.From the sentence “A force of four ounces deflects a thousand pounds”

we know that the technique is not accomplished with strength.The spectacle of an old person defeating a group of young people,

how can it be due to swiftness?”

I’d disagree with the classic on one important point though – most of the traditional martial arts in fact do go beyond the strong dominating the weak, because without that key principle there is not much of an art left in the martial art at all. And I don’t know about the idea of defeating a “group” of young people either (that would be a tall order for any martial art, or martial artists), but to me the classic is suggesting that skill and technique can supersede the natural advantages of youth, such as speed and strength. And when it comes down to it, it’s hard to find an art that can deliver on this promise as well as BJJ can.

BJJ is one of the few martial arts where an older man (or woman) can be expected to regularly beat a younger man (or woman) by having more skill and technique, in a fully resisting scenario, thanks to techniques that manage the distance (a critical self defence skill) and use leverage and technique to overcome brute strength. That’s not to say that no strength is required, but you don’t necessarily need more strength than your opponent to make it work.

Rickson Gracie

To me, the BJJ practitioner that best exemplifies a similarity between Tai Chi and JiuJitsu is the legendary Rickson Gracie. He’s generally agreed to be the best of the Gracies. Compared to the acrobatic extravagances of today’s sport JiuJitsu champions, who favour inverted guards and bermibolos, Rickson’s style of Jiujitsu seems surprisingly simple, yet effective. There are no flashy moves, just basics done at a very high level.

The Rickson documentary “Choke”, which shows his training for a Vale Tudo fight in Japan, is essential viewing if you haven’t seen it before:

In the documentary you can see a young Rickson doing Yoga on the beach. Rumour has it that he also said he studied Tai Chi in a magazine interview, although I’ve not been able to find a transcribed version online to confirm this. Either way, it’s clear that he’s not averse to stepping outside of “pure jiujitsu” to add elements to his exercise, martial and health regimen. The cost of upholding the reputation of JiuJitsu and the Gracie family has been heavy though, and he has several herniated discs in his back, but he’s still on the mats teaching his family art, cornering his son Kron in his MMA fights and giving instruction through his JiuJitsu Global Federation. He also spends a lot of time surfing these days, instead of fighting.

If you read a Rickson seminar review, like this one, you can see that he keeps returning to two common themes – “connection” and “invisible jiujitsu”. The invisible part refers to what you can’t see happening; you can’t see where he is putting his weight and making his connection to his opponent, but you can feel it when he does it. He has detailed ways of making a connection in each position in BJJ.

This sort of teaching from Rickson, to me, is where I find the crossover between Tai Chi and BJJ to be strongest. In Tai Chi Push Hands, for example, we constantly seek to make a connection to the other person, through touch, so its a very familiar concept.

Here’s me doing some push hands:

Forget about the thing I’m trying to teach in the video, just look at the Push Hands routine we’re doing. As you can see, Push Hands very concerned with ‘feeling where the other person is’ and ‘yielding to their force without opposing it’ to neautralise the opponent. From this perspecitve, Push Hands starts to sound a lot like what Rickson is talking about in his seminars, but in a different format.

But the similarities don’t end there. When employing standing techniques Rickson also utilises some of the postural work found in Tai Chi and makes makes subtle nods towards the ‘internal’ method of body movement favoured by Tai Chi. He talks about making a connection to the ground through the feet. I’m not suggesting his ‘body mechanics’ ideas fully embrace everything you’d find in Tai Chi, but I can see the foundations of it being built.

For example, in a Rolled Up episode (3/4) from last year Rickson shows Budo Jake how to use some basic body mechanics to create a better root to the floor when meeting an incoming force while standing. He’s talking about transferring the force applied to the arm down to his foot and into the ground, then back up to move the opponent backwards. This is basic Tai Chi 101.

See here, from the beginning:

At.4.26 he starts to talk about ‘invisible jiujitsu’, specifically at 5.55 about ‘putting the weight in the hands’.

I was taught a very similar drill in Tai Chi – a kind of wrestling game, where you had to stand square on to the opponent and try to unbalance them with a push as they did the same to you. The key to doing it is to ‘put your weight into your hands’, so that when you push, it’s coming from the foot, not the shoulder. And when they push you root the push into the ground, instead of letting it push you over.

Here’s a video of me doing it from a few years ago. The camera is on the ground and not straight, so it looks like I’m leaning forward, but I’m not really:

I’m not an expert at it, and use too much arm strength, but hopefully you can see the similarity between this and what Rickson is talking about in the Rolled Up video.

Of course, Tai Chi takes this idea of creating a path from the foot to the hand to further levels of detail – first the idea of ‘pulling silk’ where you create a stretch from the fingertips (and toes) to the dantien and maintain that connection while moving, so it remains unbroken. Incidentally, the silk analogy refers to the way silk weavers pulled raw silk thread from a cocoon – you had to pull with an even pressure or the thread would break.

The next stage after ‘pulling silk’ in Tai Chi is to create windings on the muscle-tendon channels in the body, controlled from the dantien – the famous ‘silk reeling’ of Tai Chi. I think you can view this as the point where BJJ and Tai Chi diverge and head off along different paths – Tai Chi becomes highly specialised in this type of movement, while BJJ becomes more interested in the practicalities of actual fighting, and taking the fight to the ground (or just dealing with the fight on the ground) where it enters a whole new arena.

Realistically, and practically, there is no need for the type of highly specialised and, frankly, difficult, method of moving the body that Tai Chi employs for actual fighting, and also it’s questionable whether you can actually do ‘silk reeling’ type movement when on the ground, since it relies on using the power of the ground to push up from via the legs. Does that mean one art is better than the other? Well, they both are what they are, and they’re good for different things. I’ll probably leave it at that.

Conclusion

Interestingly, when I started BJJ (almost 5 years ago now) I found that my all years of experience in Tai Chi meant nothing at all on the mat when rolling against an experienced practitioner – even if they were a smaller, weaker person. Fighting on the ground is a completely different animal compared to stand-up. I was submitted as regularly as the next white belt, but I did find that my previous experience in Tai Chi meant I could learn quicker than average (I got my blue belt in a year). It let me see the concepts and principles hidden within the techniques of jiujitsu. And it helped me relax under pressure, which is a huge part of getting better at BJJ. Also, doing the Tai Chi form helped me recover quicker from the physical wear and tear which is characteristic of your first 6 months of BJJ, while your soft, squidgy body is still toughening up.

Unlike Tai Chi, which has, in a sense, become set in stone in terms of its evolution, BJJ is a constantly fluid and evolving art. Thanks to the highly competitive environment of the BJJ competition circuit, new techniques are always being created and being discarded. It’s becoming highly specialised towards what works in the most common competitive rule sets. Where I see the connection to Tai Chi is in the older, ‘original’ BJJ that was more self-defence orientated, as exemplified by Rickson Gracie. Where BJJ is headed next is anybody’s guess. Quite possibly it will evolve in several directions all at once, and it will be interesting to see if the legacy started by Rickson Gracie and his ‘invisible JiuJitsu’ lives on, or even gets expanded upon.