Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

So, my last post on what ‘whole body movement’ means in Tai Chi Chuan got some interesting reactions on the interwebs. I thought answering the comments might make a good subject for a few more articles. So let’s get going with the first of them.

On the Ancestral Movement group, Andrew Kushner writes:

“Whole body motion” is a lousy coaching cue. It neither helps people move more correctly nor is it an accurate description of what’s going on. It is possible to have “whole body motion” with only one limb moving apparently, and it is also possible to have the entire body involved but still ‘disconnected’ from an IMA perspective.

In fact this is the case with most athletic movements. Do you really think boxers and judoka don’t involve their whole body when they go to express power?

Firstly, yes, I’d agree that ‘whole body motion’ is a bad coaching cue, since it is so undefined. That’s really what my post was about – how there are different possible interpretations of what whole-body motion could mean, and what it actually means in the context of Tai Chi Chuan. Like most of the writings in ‘the classics‘, Yang Cheng Fu’s 10 important points is only useful if you already know what he’s talking about. Which makes them good as reminders, but rubbish as coaching cues.

The second point about boxers and judokas is interesting. Yes, I agree that boxers and judoka involve their whole body when they go to express power. But they do it in a different way to Tai Chi Chuan practitioners. Or at least they generally do. Sure, you could do both boxing and judo with a Tai Chi Chuan type of whole-body power, if you wanted to. But in Tai Chi you want to use as little physical effort as possible to get the job done. It’s difficult to even understand what that means and even hard to actually do it. Tai Chi movement is subtle and tricky and there’s no real incentive to train that way in combat sports where results matter and there are quicker, easier ways to get them.

Photo by Sides Imagery on Pexels.com

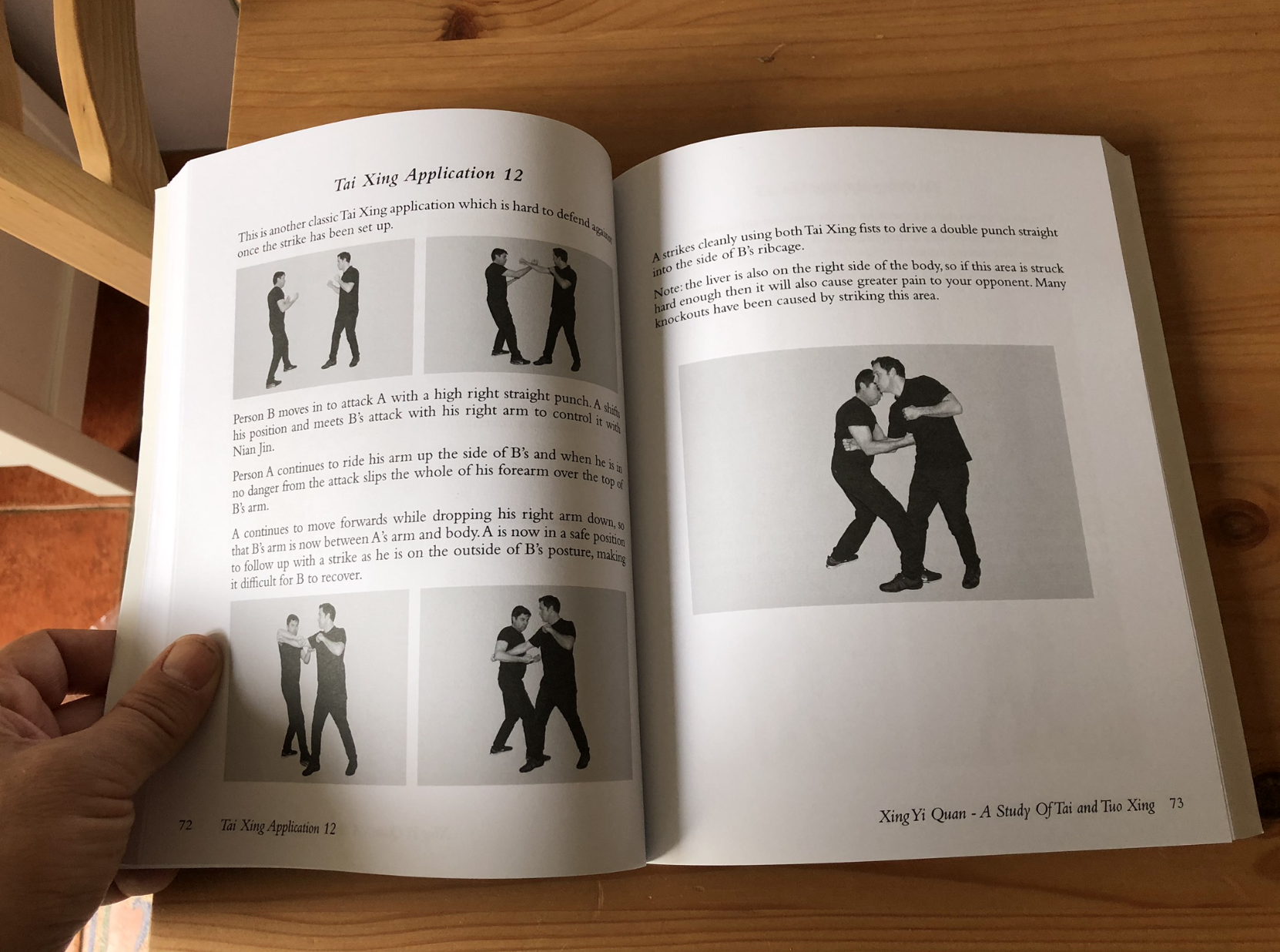

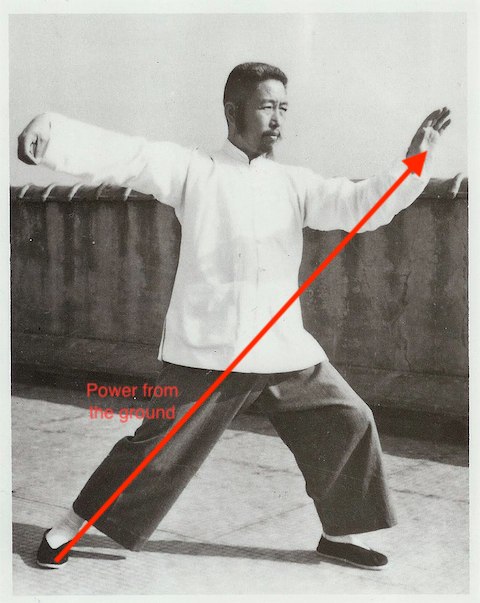

It’s not like boxers don’t use their legs when throwing a punch. Of course, they do, but do they do it in the exact way we do in Tai Chi Chuan? I don’t think so. Let’s remind ourselves what the Tai Chi Chuan way of moving is again –

1) moving from the dantien

2) power up from the ground (jin) – rooted in the feet, expressed by the fingers.

3) coiling and spiraling actions from the dantien out to the extremities and back.

That’s difficult. A strong, athletic 20-year-old in Judo can fire his hips into a throw with more than enough speed and power to get the job done. It doesn’t need to have all come from the ground to work.

“Second, there is more in common between the “robot dance” and CIMA than Graham acknowledges. It wasn’t until I learned other ways of moving e.g. Systema and dance that I realized just how blocky and ‘robotic’ the CMA’s are at their core, even flowy and ‘natural’ looking ones like taiji. In fact I think a lot of their power derives from this similarity — simple movements done well.

Still for all the similarities there are important differences between CMA and the robot dance, so it is instructive to consider what those might be.”

That’s interesting. I don’t know what Andrew’s individual experience of Chinese Martial Arts has been, but I’m always a bit wary of using my individual experience to generalise and speak for all of Chinese Martial Art. It’s a very broad church and it contains pretty much every possible version of movement you can imagine.

Is he talking about modern Wu Shu training? The 1920s GouShu experiment that got exiled off to Taiwan? The pre-twentieth century martial arts that were forced underground? Wrestling styles?

I guess, compared to Systema any martial art could be called ‘blocky’ and ‘robotic’ since Systema has no routines or patterns and has no stance, just the four pillars: movement, breath, posture and relaxation. It also looks utterly ridiculous at times. I’m actually not adverse to Systema at all and I think there’s some great stuff in there. I’ve got a good friend who is a teacher and I do want to check out his class sometime. (But it would mean time spent not doing Jiujitsu, and that’s a serious consideration, so some tough choices will have to be made!)

On balance I think there is some merit in Andrew’s criticism of CMA here. A lot of it is just a lot of forms. But again, it depends on how you train it. Are you just training forms for forms sake? I think a lot of Chinese martial arts is like this. I’ve never been attracted to systems that had a lot of forms. A form for this, a form for that. I think that misses the point entirely.

I think of ‘forms’ as being like the raft in the parable of the Buddha crossing the river.

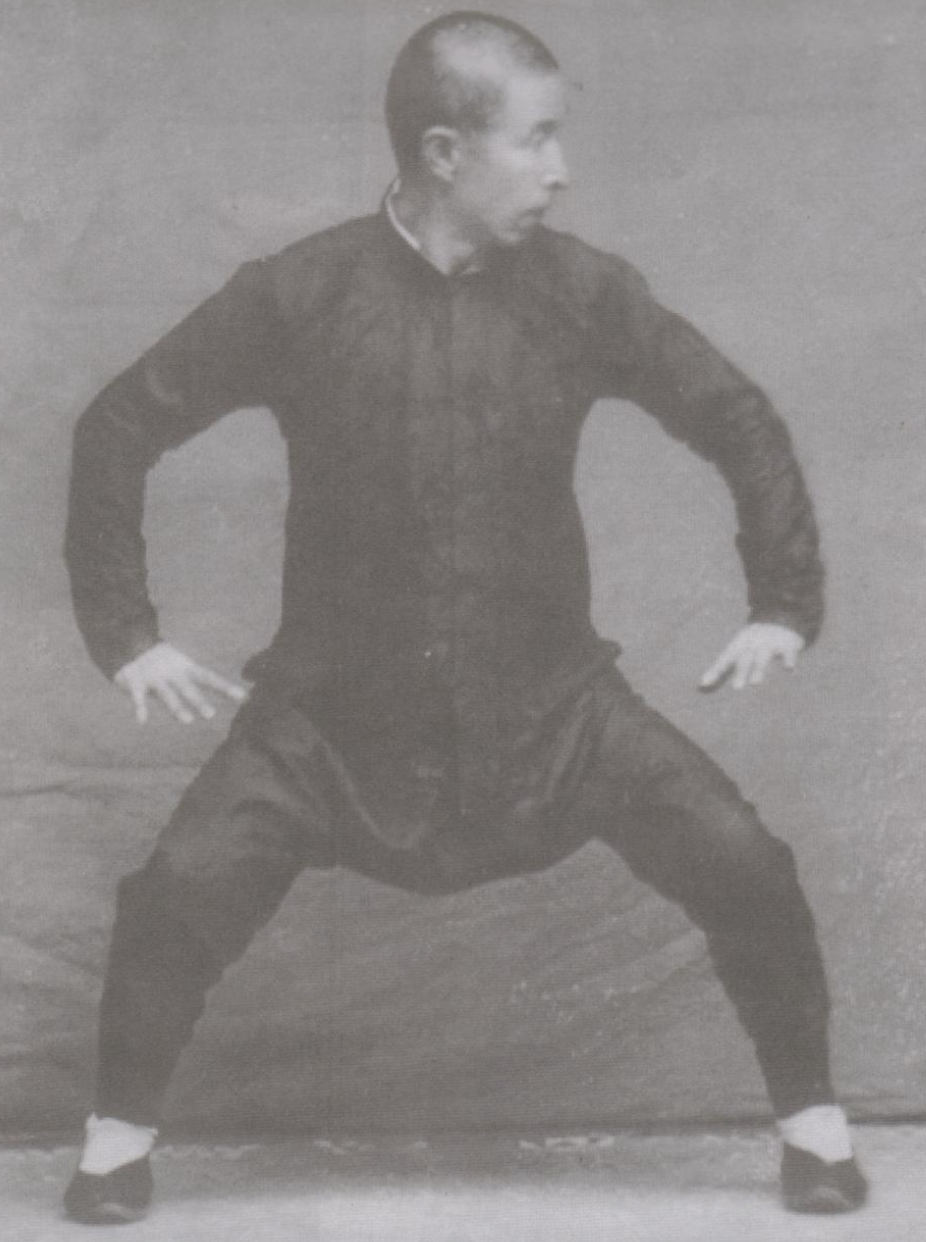

But then Andrew flips it around and praises “Simple movements done well” I think this references to things like XingYi, which has 5 fists as its base. These are quite often practiced over and over, for years. until you get very good at them. Personally, that approach didn’t appeal to me. I found the more varied animals much more interesting to practice and also more alive, less robotic, more spontaneous and useful for actual sparring. I think that’s where real power of Chinese Martial Art lies – not in practicing simple thing over and over, but in not getting too fixed down into any particular method or technique and keeping things fluid and “in the moment”.

But each to their own.