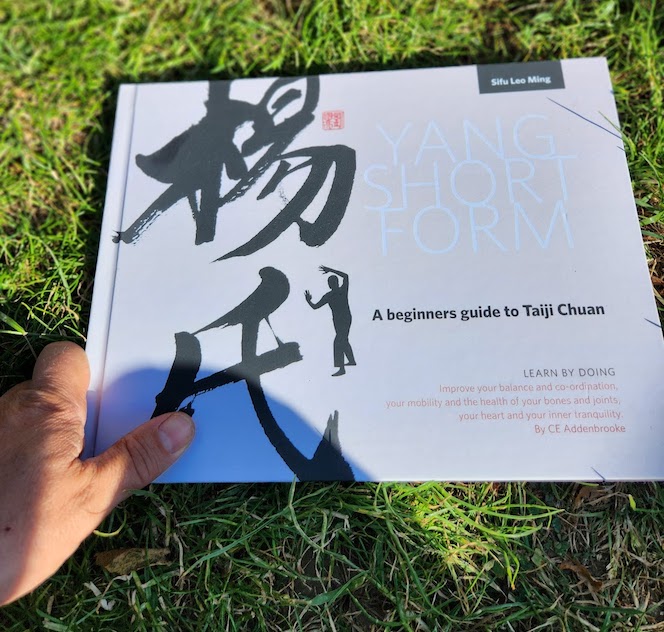

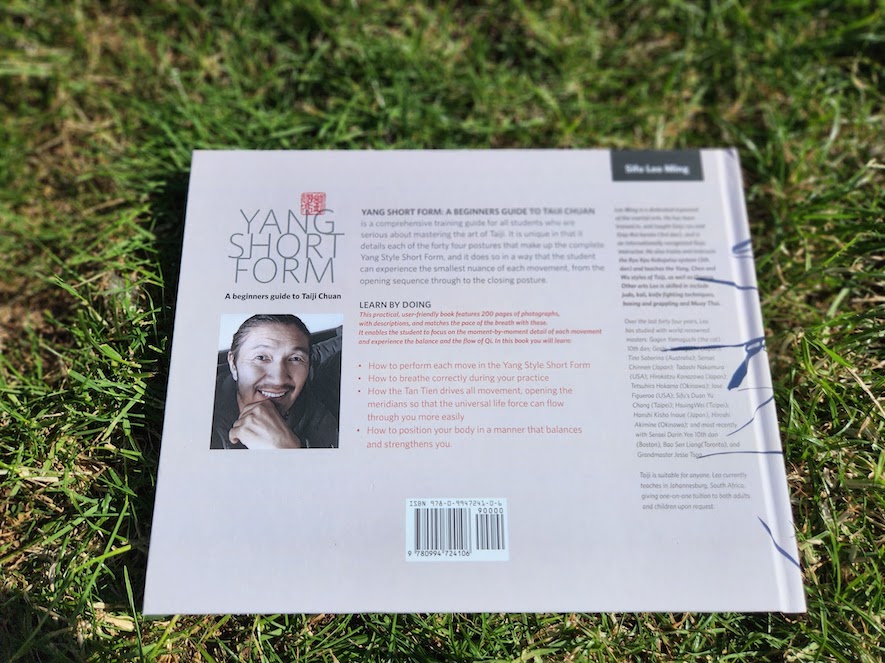

Yang Short Form: A beginners guide to Taiji Chuan, is a beautifully made, hardback coffee-table Tai Chi book, containing a brief section on history and principles of the art, over 200 colour photos mainly for showing you the form, a few verses from the Tao Te Ching to act as inspirational quotes and more.

There’s no denying that at an RRP of £49, it’s expensive. For people wondering why this book costs that much on Amazon (although you could pick it up for 18% less at time of writing), the high production values and hard cover explain the price. Printing in colour is expensive these days.

Sifu Leo Ming is the teacher who appears in the photos, and his student Caroline Addenbrooke is the author.

The main point of the book is to teach you the Cheng Man Ching short form, and if you view the book through the lens of ‘Can I learn a Tai Chi from this book?‘, it succeeds, I just have a few issues with some of the information presented here.

Consider the title

My problems start with the title, “Yang Short Form: A beginners guide to Taiji Chuan“. The Tai Chi form presented in this book is the Cheng Man Ching short form, which is certainly a Yang short form, but it’s a bit of a stretch to call it the Yang short form. People generally call it the Cheng Man Ching Short Form or the Chen Man Ching 37 form, which would have been a more accurate name, since Cheng’s form varies quite significantly from the official Yang form that belongs to the actual Yang family.

Secondly, the use of “Taiji Chuan” awkwardly mixes two different romanisation styles together in a way I’ve never seen done before, making it something of an outlier in the Tai Chi world. Tai Chi is usually either written Taijiquan/Tàijíquán (pinyin) or Tai Chi Chuan/Tai chi ch’üan (Wade-Giles), or shortened to simply “Tai Chi“. I find the decision making process of mixing the two systems together used here to come up with “Taiji Chuan” a bit baffling. Why do that?

Similarly, inside the book there’s a mix of different romanisation styles. Shaolin appears as “Shao-lin”, while changquan appears as “Changquan”, (so they’re happy to use pinyin there…) Dantien appears as “Tan Tien”. But Qi is “Qi”, not “Chi”, and Xingyi is “hsing-i”! I can’t work out the logic. In a way, so long as the system used is internally consistent it doesn’t matter, but it is a bit frustrating.

Finally, “beginners guide” is used in the title without an apostrophe! Well, that is just… wrong.

But, let’s move on from the title of the book and look at what we’ve got here.

All the history all at once

The history section starts with a pretty safe phrase, “The history of Taiji Chuan is unknown”, and if it had stopped there I think I would have been happy, but it then goes on to tell a version of Tai Chi history anyway that includes every folk tale in the Tai Chi master’s repertoire! It talks about the classic Chan Sanfeng origin story, but also has the Chen village origin story straight afterwards before giving a brief rundown of the current styles of Tai Chi, before then pivoting back further into time and linking Tai Chi to the Shaolin Temple because that’s where “qigong theory” started… If you know anything about the history of Tai Chi you’ll know that these kind of myths are probably just that, myths, but they help the marketing of the art.

There are other problems with the accuracy of information, too – there’s a picture of a statue of Chang Sanfeng in the history section which is captioned “A statue in Chenjiagou depicting the legendary Chang San-Feng”. I thought that didn’t sound right. A quick 5 minutes on Google confirmed that his statue is of Chang, but it’s found (not surprisingly) in the Wudang mountains, not Chen village, as stated. Unless I’m wrong and there are two identical statues, but I don’t think so. The most famous statues in Chen village are the statues of Chen Chanxing and Yang Luchan.

The rundown of the different styles of Tai Chi in existence today is accurate, but if you want a proper investigation of the history of Tai Chi, I’d suggest looking elsewhere.

The section on principles of Tai Chi is also very brief. It’s all the usual advice you find in Tai Chi books about relaxing, centering, evenness and slowness, etc. There’s nothing wrong here, but it’s very surface level.

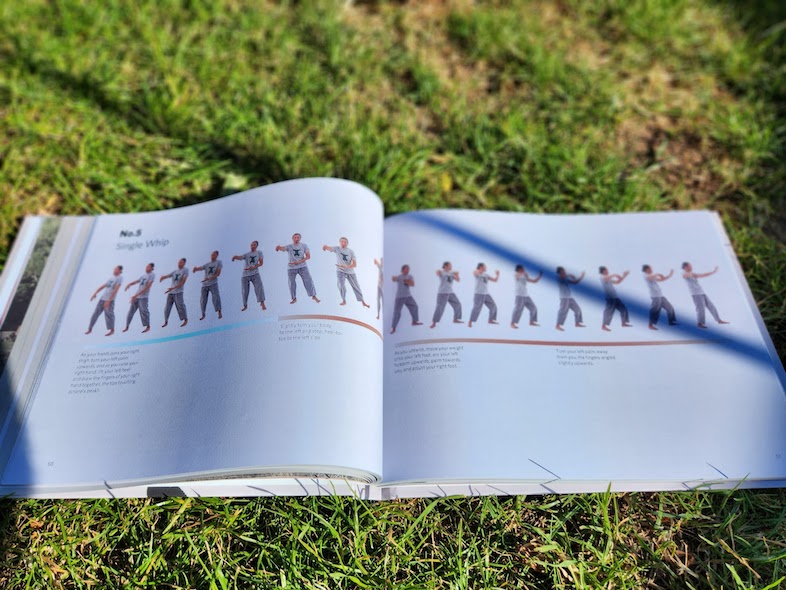

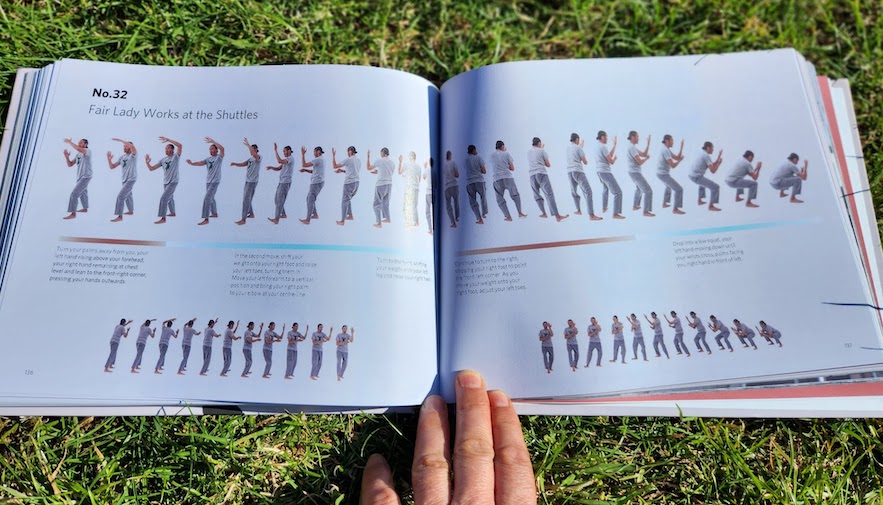

Teaching forms is where Yang Short Form gets it right. The book uses the method of breaking down each move into tiny fragments and showing them next to each other, conveying the sense of movement through the form nicely. As such you can definitely use the book as an aid to memory of this form, or even teach yourself the form from it. Take a look at this example of Single Whip:

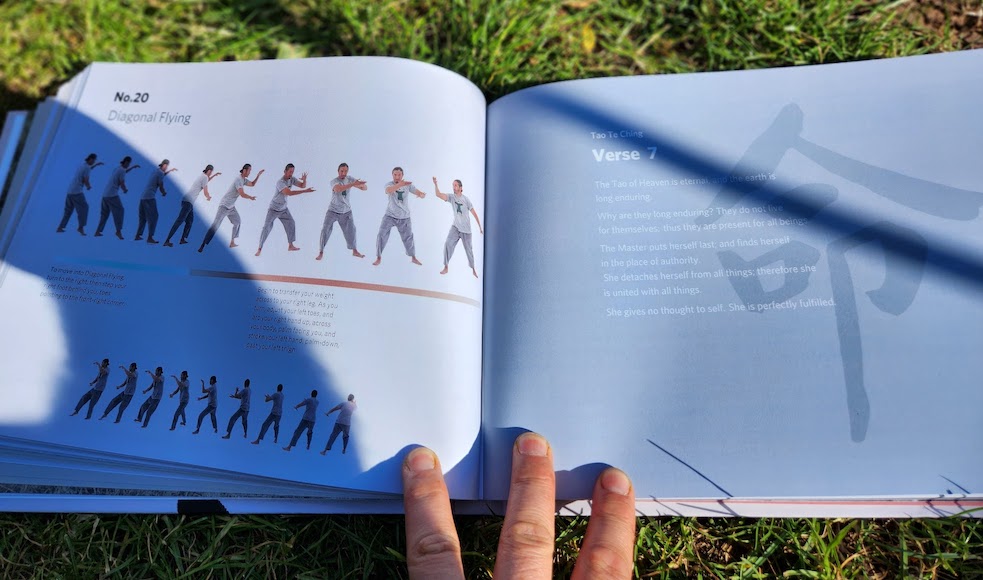

Diagonal Flying:

Of course, Tai Chi purists will say that the choreography of the form is not the important part, and that the body method is vastly more important, however, for better or for worse, the vast majority of Tai Chi practitioners in the world are not looking for a book on that. They are simply trying to learn some movements as a form of exercise for health, and this book will serve them very well.

I don’t do the Cheng Man Ching short form myself, but I have learned it in the past, and as I was looking through the movements it struck me that there were one or two idiosyncrasies presented by Sifu Leo that I hadn’t seen before. I noticed three things in particular:

1) A low squat Sifu Leo does as a transition between each ‘Fair Lady Works at the Shuttles’ move:

2) A front kick/leg raise, he puts into Repulse Monkey.

3) In Golden Pheasant Stands on one leg – he again squats all the way down to the floor between the knee raises.

This struck me as peculiar, so I checked the form against a video of Chen Man Ching, mapping the movements in his video to the ones in the book, and while the forms match (all the movements are here and none have been added), the above curiosities are not performed by Professor Chen Man Ching.

Also, there are 43 moves in the form shown here, and Chen Man Ching’s form was said to be 37, but I suppose it depends how you count the moves.

I don’t think these three variations to the Cheng Man Ching form matter that much, but I think it’s safe to say that they are not standard, so I should point them out. It’s also important to note that there are no marital applications or discussion of push hands in the book at all.

Overall, if you practice the Cheng Man Ching short form for health and you want a visual reference to remind you of the moves then this book will fit the bill – it’s beautifully designed and the form is clearly presented. If you’re looking for a scholarly discussion of the history of Tai Chi, or an in-depth dive into the body mechanics, then other books are available.

This seems like a good, honest review.

“Taiji Chuan” is a correct romanization using the Yale system. Its popularity has declined, so it is one of the lesser known systems. It gets the average English speakers closest to Chinese pronunciation without having to learn the aspiration rules of Wade-Giles or the alternate consonant pronunciations of the Pinyin system. Pinyin also borrowed many but not all of the Yale conventions. However, Yale would spell chi, chang chuan, and sying-i, so the book authors still do seem inconsistent still.

LikeLike

Thank you for your detail about the book and your clarity about the Cheng Man Ching form. I studied tai chi years ago (early 1970’s) with Professor Abraham Liu who was a student of Professor Cheng Man Ching. Tai Chi has gone through changes since those early first days in the US. It’s hard to find a “pure” C Cheng Man Ching yang style these days. Very hard to find a teacher. I’m still searching.

Regards Nancy Cuffman

>

LikeLike

Obviously a lot of thought and planning was involved in putting this book together. Based on the format and the graphics, several people must have been involved. I’m sure that they have high hopes for the success of their book.

Unfortunately, this will be one of those books that will end up on the remainder table. No matter how an author may try, the essence of tai chi cannot be conveyed in printed words and pictures. A person may try to imitate images and watch videos and try to put it into practice, but without the environment and the presence of a qualified, inspired teacher, the depth of tai chi will remain out of reach.

LikeLike

It’s sort of fascinating following the “Yang style” from inception to present. Yang Lu Chan was an indentured servant of Chen De Hu in Chen Village. Although he was allowed to study in Chen Changxing’s class (held at Chen De Hu’s house/courtyard where Yang worked), YLC was never officially taught anything more than the first Chen form, since he was not a villager: the gap in knowledge begins here. When Chen DeHu was in his 80s and about to die, Yang was released from servitude and given permission to leave Chen Village and teach Taijiquan to make a living. He was admonished to not teach reeling-silk, though.

Without Chen Village for a backup, Yang Lu Chan’s sons, Ban Hou and Chien Hou learned what they knew only from Yang Lu Chan. So the gap of incomplete knowledge gets broader.

Yang Chien Hou’s son, Yang Cheng Fu, was taught Taiji to some degree when he was young, but his first study was well-known to be Shuai Jiao, not Taijiquan. Plus, YCF was known to be sort of lackadaisical in his training. At the age of 30, after his father and uncle were dead, Yang Cheng Fu decided to start practicing what he remembered of the Chen style Taijiquan and his “official Yang form” is obviously patterned on the Chen-style Lao Jia Yilu. But Yang Cheng Fu undoubtedly couldn’t remember the form all that well, etc., so there are many marked differences in the two forms.

Cheng Man Ching is a puzzle because he claims to be a close student of Yang Cheng Fu and when Cheng made those claims mainland China was closed with no one to dispute Cheng’s claims. However, there was trouble on the horizon because the Tung family (from Tung Ying Jieh, a known major disciple of Yang Cheng Fu and someone who took challenges for YCF back in the day), said that Cheng was not telling the truth. The Tung family had (and apparently still has possession of) the actual enrollment book of students of YCF. According to the Tungs, Cheng, an occasional student, was enrolled only as a general student in the general classes taught by Yang Cheng Fu’s disciples, not by Yang himself. When China opened back up, Fu Zhongwen, the son-in-law of Yang Cheng Fu, corroborated the story of the Tungs. In other words, Cheng appears to have embellished his position and level of knowledge. The gap in knowledge increases yet again.

I’ve been interested almost exclusively in the body mechanics of Taijiquan for many years and have little interest in the style wars, but my problem with something as far removed from the original Chen’s Taijiquan as Cheng’s “short form” is that all of the intricacies of real Taijiquan and its specialized movement are missing. A book showing Cheng-style choreography can never teach how to use jin, move with the dantian, develop the qi, use reverse breathing, use fangsong, and so many other things. Assuming the student is truly interested in Taijiquan, my advice is to keep digging and to go as close to the source as possible.

LikeLike