A new episode of our Heretics podcast Xing Yi history series is out. This one tackles the formation of the Ming army. Episode 18 is available now.

The Heretics by Woven Energy podcast is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

A new episode of our Heretics podcast Xing Yi history series is out. This one tackles the formation of the Ming army. Episode 18 is available now.

The Heretics by Woven Energy podcast is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

We should stop now and again to look back to see how far we’ve come. The Heretics podcast has reached episode 100! It’s a podcast designed to challenge the way you see the world, hence the name. We cover a lot of religious topics, but also a lot of esoteric topics and martial arts. To celebrate episode 100 we’ve done a 2 hour special on Xing Yi. The first hour is a continuation of our History of Xing Yi series, but the second hour is an off the cuff discussion about Xing Yi that you might enjoy more. Expect some heretical ideas and controversy!

So, in my original post about using the Xing Yi 12 Animals to anaylse the fighting styles of modern MMA athletes (I know, it’s a small niche, but hey, I’m the only one in it!) we looked at Alex Pereira vs Jiri Prochazka and I speculated that they were good examples of the Chicken and Swallow Xings respectively.*

I left the reader with a question at the end… I asked them to take a look at another fight on the same UFC 295 card where British heavyweight Tom Aspinall took the interim heavyweight belt by defeating Sergei Pavlovich. The question was what animal style could we say that Tom Aspinall was a good example of. Take a look at the fight before reading further if, you haven’t already.

So, nobody decided to answer in my comments section but I got a few replies in private groups on Facebook, etc. One person got it half right, but they mixed two animals together in their answer, and only one was right. Interestingly most people seemed to opt for Tom being a rather large Monkey (Hu Xing). I get why, Tom is clearly bouncing in and out on his toes, despite being a massive human, but really that’s where the similarity with monkey ends. Monkey would try to attack from further out than Tom is standing, or from further in – it’s a very ‘in your face’ animal, but also a joker and a trickster. Taking pot shots, then running away. Remember the classic Monkey vs Tiger fight video? That’s Monkey. I can think of at least one modern MMA fighter who is a classic monkey – I’ll post about him in the future.

So, let’s look at what Tom actually is. He’s 100% Snake because Snake has Yin and Yang aspects. The key feature of snake is a coiling body, which can be used for either very quick strikes (Yang snake) or wrapping and coiling actions (Yin snake) for defence and grappling/locking. You can see this defensive coil aspect (Yin snake) particularly well when Tom is defending. There’s a little section in the round where he slips punches from Sergei while he coils and winds his body as he circles off – this is classic snake behaviour – just imagine if you were stupid enough to try to grab an angry snake by the neck – it would bend and coil around your hand, particularly if it was a python.

Snake’s are very aggressive, successful predators dating back to the time of the dinosaurs, and they’re always sensing forward, flicking out their tongue, and of course, they have the famous (and sometimes) venomous bite. When a snake bites the action is incredibly fast – you’ll notice that when Tom flicks out his jab the speed catches Sergei completely by surprise. For a big man he punches very quickly. The finish is so fast it’s hard to see, but Tom punches Sergei twice before Sergei can even react, steps back, looks at him, then punches him again sending him to the canvas:

Throughout the fight, Tom is flicking out single jabs and single low kicks too, very quickly.

Snake in Xing Yi is also associated with locking and grappling actions – we didn’t see any from Tom in this fight, but that doesn’t change the character that Tom is showing. (He’s actually a very accomplished grappler as well).

But what about Sergei? Well, we didn’t see much from Sergei in this fight, but from what we saw I’d vote Bear for him. His stepping is short as are his rounded punches. He’s incredibly powerful, and he landed the first strike of the match on Tom, which was so powerful he almost finished it there and then. Luckily for Tom he managed to absorb it. In our style we always include Bear and Eagle together, so I think Sergei’s got the potential for some Eagle strikes too, but the fight simply didn’t last long enough for him to show them.

If you’re talking about snake movements performed in Xing Yi then it looks something like this:

You’ll notice you can see the elements I’m talking about here – fast strikes, coiling movements and grappling applications.

Here’s a video of me doing some Xing Yi Snake. I’m showing some berehand and sword here, but you can see it’s all the same thing.

* I suppose this post needs to end with some sort of “this is just my opinion” type of disclaimer. But I find people tend to get offended about everything they possibly can regarding Xing Yi these days, so I’m not going to loose too much sleep over it. And obviously Tom has probably never heard of Xing Yi – I’m just using it as a tool to analyse his fighting style. And if you want to enter an MMA match then MMA training is obviously the best way to train for it, not Xing Yi.

There are different lineages of Xing Yi, it’s been transplanted to different countries, and it’s very old, so it’s quite possible that none of my understanding of Xing Yi snake resonates with your particular lineage. It’s a sad fact that most Xing Yi animals have become just a set of techniques or moves, that have long since lost any connection to actual biological animals – successive waves of crushing political ideology, (both nationalism and communism) imposed on a marital art at the barrel of a gun will kind of do that. I will say however, that my understanding of Xing Yi snake is not really based on a particular style of Xing Yi, or a way of doing the move, but on tying to get back to what real snakes do. And I won’t say I wrote the book on Xing Yi Snake, but I did write one chapter of it.

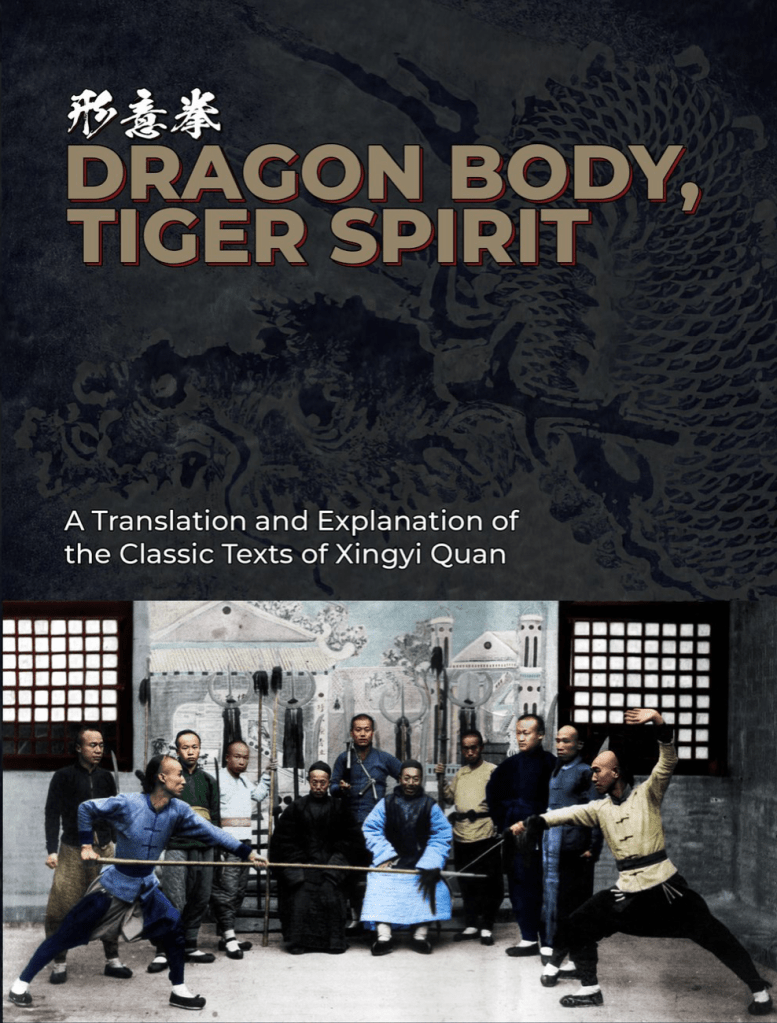

Xing Yi is one of the oldest Chinese martial arts that is still practised today, and so naturally it has attracted a large variety of writings over the hundreds of years of its existence. These various writings can be found scattered about in different lineages and books, but now Byron Jacobs has collected them together in one weighty tome – Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit – and included not only the original Chinese texts, but also his own English translation and commentary on them.

Originally from South Africa, Byron is a student of Di Guoyong of the Hebei lineage of Xing Yi, and lives and trains in Beijing. At one time he was a member of the technical committee of the International WuShu Federation, so he has been able to meet and talk to practitioners of other martial arts and Xing Yi lineages. He runs the Mushin Martial Culture website that offers online tuition, as well as provides excellent YouTube videos on all aspects of Chinese martial culture, history and practice.

(Full disclaimer for this review: I’ve known Byron for years, and while we’ve never met in person I’d consider him a friend. He’s been a guest on my podcast and I’ve been on his.)

Being interested in design, I always like to spend a bit of time talking about the cover of a book in my reviews, but in this case it’s not really an indulgence because discussion of the cover is properly warranted. Not only is it well designed but it contains a fully colourised reproduction of the famous black and white photo of Xing Yi masters Guo Yunshen and Che Yizhai, taken when Guo visited Che’s martial arts school. Now, since this is the only picture that can reliably be said to exist of Guo Yunshen, it has always been treasured by practitioners in the Hebei lineage of Xing Yi, of which I would count myself as one. Colourising the famous photo is an audacious and brilliant idea. The colours and shading on the faces in particular all look natural and really bring Xing Yi to life as a living breathing art practised by real people, rather than an ancient art lost to history. Did Guo Yunshen actually wear blue robes? I don’t know, but he looks great in them.

Incidentally, the photo is misleading, because the martial arts display Che and Guo are watching is definitely not Xing Yi. Che and Guo are the seated older gentlemen in the centre, watching two performers of what looks like a more Shaolin-derived art, or even a theatrical performance. The stage they are sitting on, complete with performers doing martial arts, and a painted city background behind them makes the whole thing look very much like a Chinese theatre.

The meat of Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit is the collection of all the classic writings on Xing Yi, including a lot of the stuff that came out during the Republican-era martial arts manual-writing craze, as well as older material. Everything is provided in original Chinese characters first, then as a translation into English and finally there is a commentary by Byron which explains what the classic is about. For me the most important classics in the Xing Yi corpus are Yue Fei’s 10 Thesis, since these are amongst the earliest writings on Xing Yi, and a lot of the other writings are based on these, but rest assured they’re included here. In fact, there’s everything you could want, including the Five Elements Poems, Cao Jiwu’s Key extracts of the 10 methods, the 12 animals poems and more. There’s also a section called “Nei Gong Four Classics”, which is a supplementary text included from the Song style lineage of Xing Yi. The classics are bookended with two different sections – the book starts with a short article about the history of Xing Yiquan, written by Jarek Szymanski, which aims to dispel some of the myths that have built up around the art, and ends with some well-researched biographies of famous Xing Yi masters written by Byron. As a practitioner of Xing Yi you’ll find these biographies useful because the names of old masters often crop up in Xing Yi discussion.

I can’t speak for the quality or accuracy of the translations themselves since I’m not a Chinese writer or speaker, however my impression through comparing Byron’s translation here to others is that Byron has used his martial arts knowledge, and specific Xing Yi knowledge to present what he thinks the real message that the classics are trying to be convey is, rather than go for a literal translation each time. This is the best way to approach martial arts texts, as often a literal translation will sound nonsensical, and just make an English speaker scratch his or her head.

Having the actual text of the classics all gathered together in one place is an invaluable resource for any Xingyi Quan practitioner. That alone makes the book worth getting, but what really tips the balance is Byron’s commentary. He’s always clear, down-to-earth and practical. He does his best to interpret old texts that can often be esoteric and difficult to understand into something that makes sense to practitioners living in this day and age. Apparently, this book took him 10 years to complete, and you can see why. He must have spent a long time agonising over his translations and commentary before committing to a final version – nothing here seems rushed, hurried or half-baked. Everything has been carefully considered.

The casual reader, or beginner in Xing Yiquan, needs to be aware that this is not a “how to” manual – a lot of the Xing Yi classic are about things like endlessly dividing the body into sections and saying how one part works with another, which is not much use to you if you just want to learn how to do a Bengquan. They are full of things like “the eyes connect to the liver, the nose connects to the lungs” – i.e. things that aren’t that much use for practical application. There is a lot of this stuff to wade through if you are going to read the book from start to finish in full. However, having said that, Byron’s commentary on the 5 Element poems (the section of the book that deals with the Xing Yi 5 Element Fists – Pi, Beng, Zuan, Pao and Heng) is so detailed and practical that it does almost function as a bit of a How To. If you are in the process of learning Xing Yi you’ll find this section invaluable. You’ll learn where to put your elbow, fist, feet and how to move your body. And there’s a picture of Byron performing each fist, too.

I did find myself having small differences of opinion with Byron’s commentary on occasion, but it’s always over very small details or emphasis, and it feels like nit-picking to list them all, but I think it highlights an important point, which is that translation relies on interpretation and because we come from different lineages of Xing Yi I think it’s only to be expected that we’d have slightly different ways of looking at the odd thing. And you too, dear reader, will probably have small differences too, if you are already a Xing Yi practitioner. If there weren’t small differences between lineages, then there wouldn’t be different styles of Xing Yi in the first place.

For me the best part of this book is the 12 animals section. I’ve always found the 12 animals to be the most fun part of Xing Yi, and if you’re a fellow 12 animals fanatic like me then you’ll love this section. It’s also the largest section of the book, and is illustrated with pictures of the animals being described. For each animal there is a poem written by Byron’s own teacher Di Guoyong, followed by a discourse on the animal written by Xue Dian, taken from his 1929 Republican-era manual “Discourse on Xing Yi Quan” (which was written at a time when it had become popular to include aspects of Chinese philosophy and medicine in martial arts writings). Byron translates both and provides his own commentary. There’s such limited writing about Xing Yi animals available that it’s fantastic to hit such a rich vein of Xing Yi animal discussion. My experience has been that every lineage of Xing Yi has slightly different ideas about what a few of the 12 animals are, particularly “Tai” (which gets called everything from hawk to ostrich and phoenix) and “Water lizard” which gets called a turtle, an insect or a crocodile by some. The view presented here is Di Guoyong and Xue Dian’s (amongst many others), that Tai is a small hawk and Water lizard is a mythical creature being one of the 9 sons of the dragon that had a turtle’s shell.

It’s the spirits of these animals that infuse all Xing Yi practice – even if you’re doing the 5 elements or SanTi, you are still admonished to observe ‘bear shoulders’, ‘tiger head embrace’, ‘dragon body’, ‘eagle claw’, and ‘chicken leg.’ So, it’s great to see such a large section of the book, which gets its name from the dragon and the tiger, devoted to them. Di Guoyong’s poems and Byron’s commentary here are especially valuable, particularly in regard to the intent and particular features of each animal.

As always with Chinese martial arts classics, these are not writings you read through once and put on the shelf, having absorbed all their insights. Instead, you need to return to them again and again over the course of your life and dip in and out. You’ll find this reinvigorates your Xing Yi practice and each time you re-read the same section you’ll discover new insights. Picking the book up and turning to any page, it’s not hard to find something to be inspired by and to get you motivated to go outside and practice.

If you are a Xing Yi practitioner then having everything here in a single book will prove invaluable to you and Byron Jacobs has done every practitioner a great service by completing his magnum opus. Even if you are a Tai Chi practitioner, I’d still say you should get this book, as many of the ideas contained in all internal arts found their first flourshings of life in Xing Yi and the Xing Yi classics. Highly recommended.

Rating: 5/5

—

Where to buy::

Direct from Mushin Martial Culture

If you want to find out more about the book then I’d recommend listening to Byron’s interview about this book on Ken Gullette’s podcast.

You can also buy a reproduction of the cover photograph from Byron’s Mushin Martial Culture website.

So, a heads up about a couple of new books on the way, a robot teaching Tai Chi and a seminar write up that’s worth a mention. This post actually makes me think, should I be doing a newsletter? What do you think? Do you want one? Would you read it? Let me know!

Byron Jacob has a new translation of the Xing Yi Classics, Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit, coming out, which looks like it will include a chapter on the history of Xing Yi written by Jarek Szymanski who you may know from his popular website China from inside.

This is looking like it’s going to be good. The title is a nice play on “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” and it refers to things mentioned in the Xing Yi Classics. The cover also features a nicely-colourised version of the only photo we have of the famous Xing Yi master Guo Yun Shen, which has been very nicely done. (Master Guo is the guy seated centre right, and wearing the light blue tunic, next to Master Che.)

There have been many books that contain the Xing Yi classics translated, of course, but I’m hoping that Byron’s commentary will be the thing that makes this one different.

Byron says: “Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit will be available in hardcover, softcover as well as digital versions. To be notified of release visit mushinmartialculture.com and sign up to the newsletter.”

I’ll do a review once I get my hands on a copy.

Another nicely presented book on my horizon is Yang Style Short Form by Sifu Leo Ming and Caroline Addenbrooke. The short form in question is the Cheng Man-Ching Tai Chi form, and calling it the “Yang Short Form” is a bit of a liberty, since it is not the official Yang Short Form. But names aside, it looks like it’s going to be interesting.

Here’s the description:

“A beginners guide to Taiji Chuan is a comprehensive training guide for all students of Taiji who are serious about mastering the art of Taiji. It is unique in that it details each of the forty four postures that make up the complete Yang Style Short Form, and it does so in a way that the student can experience the smallest nuance of each movement, from the opening sequence to the closing posture.”

It sounds interesting, especially since it goes on to say it will teach you how to breathe correctly during your practice and how the “Tan Tien drives all movement, opening the meridians so that the universal llife [sic] force can flow through you. “

A spelling mistake in the description of the book on the website (“llife”) is a bit of a red flag, but that could be Barnes & Nobles fault, and nothing to do with the book. However, I’m curious about the use of “Taiji Chuan” as a Romanisation on the cover though, since it seems to mix both Pinyin and Wade-Giles Romanisation systems. I have genuinely never seen anybody mix the two quite like this before. It’s usually either “Tai Chi Chuan” or “Taijiquan”. This will upset some people, I’m sure, but I don’t mind.

I’ll be reviewing the book soon.

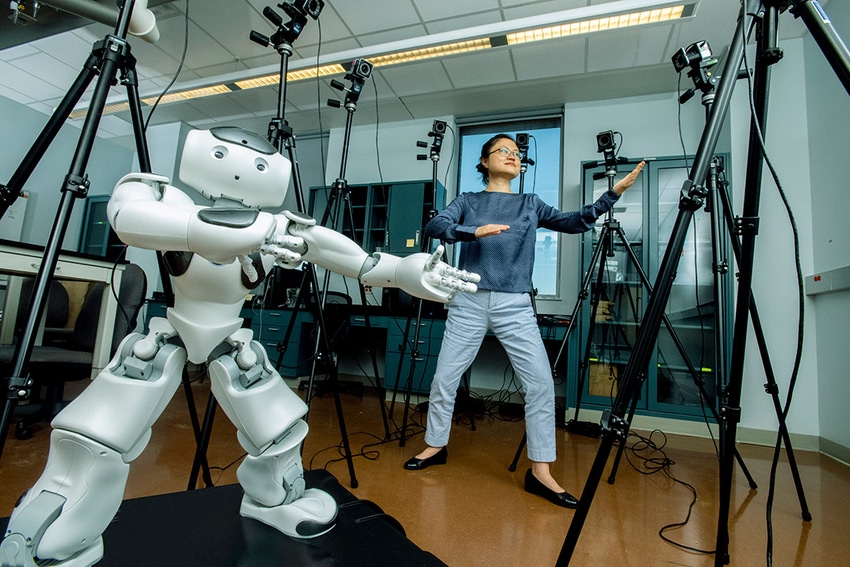

I guess it was inevitable, but somebody has made a life-size robot that teaches Tai Chi.

Depending on how it works (there’s no video!) this looks quite impressive, however, I’m left with one burning question – why? I don’t know how many thousands or millions of dollars it took to create this robot, but economically I’m pretty sure that paying Bob, your local Tai Chi teacher $50 to teach Tai Chi to the people in the old folks home once a week is a business model that is going to be hard for a multi-million dollar robot to beat. This looks like a solution in search of a problem to me.

Let me give a shout out to my friend Ken Gullette of Internal Fighting Arts for his write up of a recent seminar with Chen Tai Chi mastermind Nabil Ranne in Philadelphia. Here’s a quote:

“What impressed me most about Nabil’s teaching was the level of detail. And there were differences — in the shorter stances where feet are parallel most of the time, in the shifting of weight, in the awareness of different jin in each movement, the fullness of the dan t’ien and the coordination of the mingmen, the opening and closing of the chest and back, the folding of the chest and stomach, the closing power in the legs, the grounding from the heels, the stability of the knees and the spiraling through the feet, and connecting it all in each movement; and peng — always maintaining peng, which I have worked on for over two decades but still learn new aspects.”

Nabil teaches Tai Chi in the Chen Yu lineage, and to my eye seems by far the best of the teachers available if you want to follow that particular line of Chen style. Plus, you can learn with him online at the Chen Style Taijiquan Network

If you want to get a quick glimpse of his style of Tai Chi then check out this Instagram page.

Here are 3 things I wrote this week that you should read:

1. The power of connection with Henry Akins:

I came across this video recently of Henry Akins explaining the concept of connection in BJJ, as taught to him by Rickson Gracie, and it doesn’t half remind me of Tai Chi…

2. Way of the Warrior episode: Shorinji Kempo

The classic BBC TV series, Way of the Warrior’s episode on Shorinji Kempo just appeared online, and it still holds up today.

3. Where should the elbows be in Xing Yi?

This blog is about a weird quirk of the Xing Yi world. There’s a surprisingly large amount of online debate in Xing Yi circles about where the elbow should be when performing Xing Yi.

If you haven’t checked The Tai Chi Notebook out on Facebook then please do, and why not give our Instagram page a look too, and our YouTube channel?

There’s a lot of great martial stuff in Xing Yi Quan, which is feeling more and more like an untapped resource these days. With that in mind I interviewed one of my old training partners, Mike Ash, for the latest episode of my podcast. Mike has always been interested in training Xing Yi Quan as a martial art, and that’s what we talk about. He’s also practiced plenty of other martial arts and has recently started a new study into Taijiquan.

We talk about all of that, plus the spiritual side of martial arts. Here’s the podcast:

Compared to solo forms in Chinese martial arts, a lot of questions you might have about why we do this, or don’t do that, are immediately obvious in application on a living, moving human being. And if they don’t make sense in that context, then you have to start asking yourself if what you’re practicing really has any point at all?

Switching the emphasis away from solo form doesn’t mean you have to be doing a sort of life and death battlefield combat every time you practice, it just means you need to be thinking about the other person, not yourself, so much.

Here’s one drill we practice in our Xing Yi system, called “5 Elements Fighting” – in its most basic form (shown here) it’s two people following the creative/destructive sequence of the 5 elements, so for example, your partner attacks with metal, you respond with fire, he responds with water, and so on. Later on you can improvise and vary the elements more so that you respond to metal with wood, or earth, for example. You can also add methods in from the 12 animals. But the idea is to keep a spontaneous feel, even if you’re following a set pattern, as we are here.

Bagua and Xing Yi are two styles that have historically been trained together. The story you usually read is that martial artists living in Beijing in the 1900s rooming together found the two styles to be complimentary and therefore a long history of cross training naturally arose between them. I think this description of history is true, however, I often wonder if the real story is that earlier in time the two styles sprang from the same source, so this period was more of a reuniting of styles than two separate styles meeting?

We speculated about the origins of Baguazhang before in the Heretics episode I did with my teacher. That one seemed to upset a lot of people, especially those were emotionally invested in Baguazhang, but hey it’s not called the Heretics Podcast for no reason! You’re going to get an heretical view of things there, and that will always upset people. Perhaps we should have put a big disclaimer on the front! If you’re going to listen to it, we’d suggest emptying your cup first. But anyway…

If we forget historical lineage questions for a moment and just look at the arts as presented today, it’s not hard to see a connection between the two. The stepping is very similar. Xing Yi normally steps in a straight line, but once you look at the turns at the end of each line you start to see what is clearly the same sort of stepping that is used in Baguazhang’s circle walking.

I think this is a very good video by a martial artist called Paul Rogers explaining how Bagua circle walking is basically two steps – an inward turning out step bai bu (inward placing step) and kou bu (hooking step).

Notice that his student is asking him questions about why they circle walk in Baguazhang and he keeps returning to the same answer, which is “you could do it in a straight line”. The problem with doing things on a straight line is that you need a lot of space, doing it in a circle helps you make more efficient use of whatever space you have. So, it’s the steps that are important, not the circle.

Here’s a short article about the two steps and their usage in Baguazhang. Plenty of styles of Baguazhang do have straight line drills too. And when you take the circle walking away, I think the connection between Xing Yi and Baguazhang starts to become clearer, at least to me.

In the Xing Yi lineage I’ve been taught the animal that most looks like Baguazhang is the monkey. These days Xing Yi is know for short little forms (or Lian Huan: “linking sequences” -as we prefer to call them) however I believe this is a result of years and years of politically-directed reformations being applied to the rich and varied martial systems that existed before the Boxer Rebellion. After the Boxer Rebellion and the religious secret societies that fueled it, there was an effort to strip martial arts away from any religious connections. Then came the Kuo Shu movement (we’re simplifying history here, but several authors have written about this – have a look on Amazon, and this video from Will at Monkey Steals Peach will help) and then the Communists arrived with the WuShu movement. The result was that the rich and varied lineages of Xing Yi became standardised, often into short sequences that could be easily taught to large groups. In any case, the idea of set sequences doesn’t have to be the be all and end all of martial arts. Some teacher encourage students to create their own, once they have a good enough understanding off the principles.

We have an extended linking sequence for Monkey, taught to me by my teacher. Here’s a video of me doing a fragment of it, being a Xing Yi Monkey in a forest grove. My natural home :). I’ll put the full video in my Patron’s area if you want to see more of it.

But look at the steps I’m doing – can you see the bai bu and the kou bu? I think that if I added circle walking into that it would be almost indistinguishable from Baguazhang.

This begs the question, which came first? Xing Yi is historically older than Baguazhang, but I think because of the mixing of the arts, they both influenced each other at this point, and possibly are the same art to begin with!

I like to think of the best answer to the terrible question that plagues martial arts lineages of “which is oldest?” is “right now, we are all historically equidistant to the founder”.

One of the hardest things I think that there is to convey in Xing Yi, to the perspective new student, is how the 5 fists work with the stepping. All the time I see people doing the arm positions of the five fists in a highly stylistic and precise way, but the body isn’t right. If the body isn’t right then the fault can usually be found in the legs and waist, and most likely it’s the stepping. In Xing Yi your stepping is the delivery system for the power of the body.

The words of the Xing Yi Classic of Unification apply here:

“When the upper and lower move, the centre will attack.

When the centre moves, the upper and lower support,

Internal and external, front and rear are combined,

This is called “Threading into one”,

This cannot be achieved through force or mimicry.”

i.e. everything moves together, as one.

In this video I look at some of the common faults I see in Xing Yi stepping, which could be described as problems of partiality. First, the foot arriving before the hand, then the hand arriving before the foot, and finally the foot and hand landing (i.e. finishing their journey) at the same moment with no penetration.

The real Xing Yi stepping is deeper and more penetrating. You’re hitting the person (or bag) while your front foot is still in the air, as you move through them, displacing their mass. That’s the trick.

(N.B. this style of striking in Xing Yi is more popular in the Hebei style – other styles of Xing Yi have different specialties).

This Xingyiquan video caught my eye recently. It’s a good performance and demonstrates a nice range of material drawn from Xing Yi’s animals and elements. The performer is doing it well, and using some untypical examples of the animals in some cases, which adds a nice bit of variety.

Check it out:

Xing Yi is typically split mainly into two big demographic styles known as Shanxi and Hebei. The video shown here is a good example of Hebei style. It’s practiced by Sun Liyong, a famous Xingyiquan master from Beijing Simin Wushu Club.

If you’d like to know more about the different styles of Xing Yi and how they evolved then check out my history of Xing Yi podcast series.