Tai Chi is just one of a number of Chinese martial arts that have extended forms practice as a key component of their training methods. An incredible amount of time in Tai Chi is dedicated to performing the form in just the right way. Of course, there are lots of martial arts that don’t have forms, but they tend to be more sportive and wrestling based, although striking arts like boxing don’t have set forms either. Exactly why so many Chinese martial arts have forms at all is another question – one that relates back to their cultural origin and use in entertainment and religious festivals, and has relatively little to do with martial efficiency. It’s a contentious point, so for now let’s just accept that most Chinese martial arts today do have forms, and if you’re going to practice a Chinese martial art in 2022, then you’ll be practicing forms too.

In my training I’ve been exposed to various Chinese martial arts, and they all had a number of “set in stone” forms to train, until that is, I was introduced to Xing Yi. Or rather, I should say, to my Xing Yi teacher. His method of teaching Xing Yi was entirely different to most modern teachers – he really didn’t like the idea of set forms. Beyond the 5 Element form (the basics of Xing Yi) he didn’t really believe that any form should be ‘set in stone’. In fact, he wouldn’t even let you call them “forms”. You had to metaphorically put a pound in the swear jar every time you said the word “form”. He preferred the term “linking sequence” (lian huan, in Chinese) because it implied that the postures were linked together and could just as easily be linked together in an entirely different way. This is not entirely true, either. Sometimes he would teach you a particular sequence that was the way one of his teachers did it, and we’d call it the “master xyz linking sequence”, on the basis that you had to start somewhere, but if you ever quizzed him too deeply about a particular movement sequence then the answers would soon start to turn into the “well you could do it this way, or you could do it this way…” territory. He really didn’t want to be pinned down into a specific way of doing anything.

I think the reason he was like this is that he didn’t want to kill the natural creativity in his students, and he wanted to keep the practice vital and alive. It should be obvious that your goal in martial arts is to be a formless fighter – even a small amount of light sparring will reveal the universal truth to you that if you try and adopt fixed methods to a live situation, the results are never good. To deal with any kind of live situation you need to be able to respond and adapt freely to whatever is happening. I think he saw the popular “fixed forms” training method as being part of the reason that some Chinese martial arts were less than successful when applied for real. It was also the way he’d been taught Xing Yi, and he wanted to teach in the manner in which he’d been taught. Of course, this makes it a lot harder to teach – having a few set forms makes teaching much easier, and also transfers to large groups well. Being spontaneous requires much closer attention from a teacher and is almost impossible to expand to teaching larger groups of people. The best class size is always 1-1, and commercially that’s a hard thing to pull off. Luckily money was never part of the equation when we trained! I can’t say his method was universally successful in creating good students either – it’s definitely not. I’ve seen students of his who ended up being pretty delusional about their own abilities from following this method. It requires time (years) of prolonged contact so that you can absorb a martial art this way. If you get separated from the teacher too much then you can easily go off on the wrong track. It’s a bit like throwing mud at a wall – sometimes it sticks, sometimes it doesn’t. And sometimes the mud decides it’s somebody who has nothing left to learn from other people, and develops delusions of grandeur while trying to maintain the illusion of being humble. But, c’est la vie.

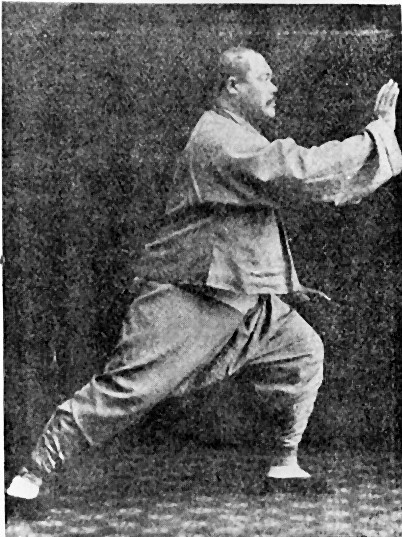

Anyway, I’ve peppered some video of me throughout this post so you can see some examples of what I mean by linking sequences – these are little Xing Yi linking sequences I’ve create to fit the space I’m working in. I like this sort of practice where you create new links each time you practice. You can combine different animals and elements in an almost endless number of variations. You can even do the movements from one animal but in the style – the xing – of another. Each day you train is different and depends on how you feel and the environment you’re training in. In fact, letting your environment (preferably, nature) into your practice is part of the training.

Now contrast that to typical Tai Chi training – you practice the same form in the same way, every day, for the rest of your life. Sounds a bit dull, doesn’t it?

Well, perhaps not. While the sequence in a Tai Chi form never varies, you can introduce a tremendous amount of variation within that fixed frame. This was how my Tai Chi teacher taught me, years before I started Xing Yi. After you’d learned the form you’d do the form in different ways, depending on what you were working on. The size of the postures could vary, the height of the postures could vary, the speed could vary from very fast to very slow, or you could focus on the breathing, on separating empty and solid. Again, the list was almost endless. It worked better if you stuck to one particular ‘thing’ for a good few months though, before you moved on to the next. Again, close contact with a teacher is required, over years.

Once the Communist ideology took over in China it infiltrated everything, including martial arts, and it’s influence is still there today. The Communist ideal is that everything looks the same, and is done in the same way. The individual identity is subsumed by the group identity. You can see this influence in the martial arts of the period and its effects echoing into modern times. Row upon row of silk pyjama-wearing Tai Chi people practicing exactly the same form in perfect unison. If you want to get good at martial arts, that’s the thing you want to avoid. And if you’re thinking right now that your practice doesn’t involve enough spontaneity or creativity, then perhaps some of the ideas contained in this post can help.