I was giving the Tao Te Ching the cursory glance I occasionally give it recently. I’ve got the copy shown above. I usually flick to a random chapter, read it three times and ponder it deeply. Well, as deeply as I am able to. I landed on chapter 61, and the next day I landed on chapter 8. These two seemed to be linked in theme, so I thought I’d say something about them.

Incidentally, I really like the Stephen Mitchell translation. I’ve no idea how accurate it is compared to the Chinese, but all translation seems to involve some interpretation, and I like the way he’s done it.

Here’s chapter 61:

61

When a country obtains great power,

it becomes like the sea:

all streams run downward into it.

The more powerful it grows,

the greater the need for humility.

Humility means trusting the Tao,

thus never needing to be defensive.

A great nation is like a great man:

When he makes a mistake, he realizes it.

Having realized it, he admits it.

Having admitted it, he corrects it.

He considers those who point out his faults

as his most benevolent teachers.

He thinks of his enemy

as the shadow that he himself casts.

If a nation is centered in the Tao,

if it nourishes its own people

and doesn’t meddle in the affairs of others,

it will be a light to all nations in the world.

and chapter 8:

8

The supreme good is like water,

which nourishes all things without trying to.

It is content with the low places that people disdain.

Thus it is like the Tao.

In dwelling, live close to the ground.

In thinking, keep to the simple.

In conflict, be fair and generous.

In governing, don’t try to control.

In work, do what you enjoy.

In family life, be completely present.

When you are content to be simply yourself

and don’t compare or compete,

everybody will respect you.

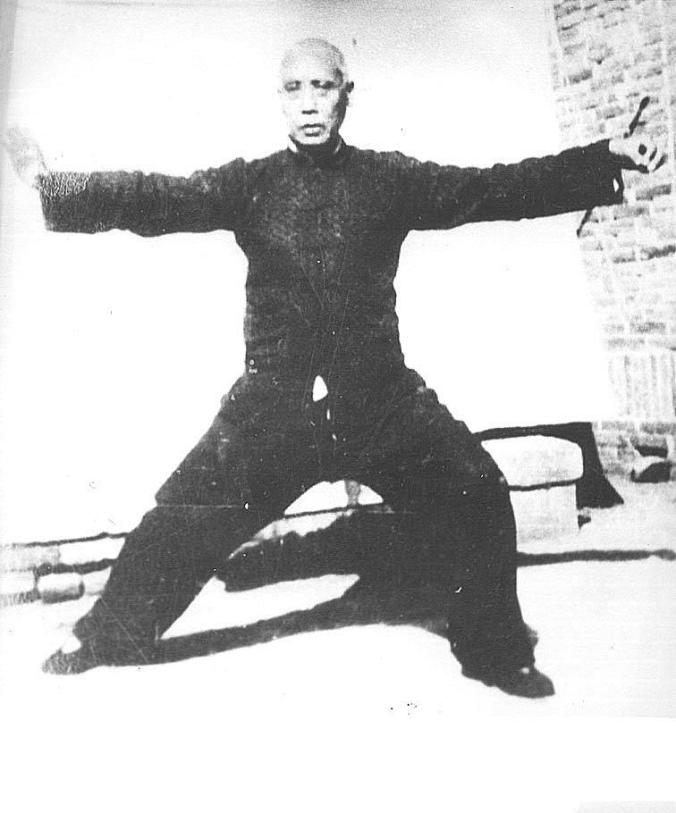

So, firstly let’s look at the imagery of water, one of the classic symbols of the Yin side of the Taiji diagram. Both chapters use water as a metaphor for the correct way of acting or being in the world. It’s a theme that repeats through the Tao Te Ching, and also throughout the history of Asian martial arts, even in modern times. I’m thinking of Bruce Lee in the infamous interview where he says “Be water, my friend!”

I was reading another article about Wing Chun today by Ben Judkins, which also expanded upon this idea of softness overcoming strength, and how this idea has permeated Asian martial arts:

Early reformers in martial arts like Taijiquan (Wile 1996) and Jujitsu sought to shore up their own national identities by asserting that they brought a unique form of power to the table. Rather than relying on strength, they would find victory through flexibility, technique, and cunning (all yin traits), just as the Chinese and Japanese nations would ultimately prevail through these same characteristics. It is no accident that so much of the early Asian martial arts material featured images of women, or small Asian men, overcoming much larger Western opponents with the aid of mysterious “oriental” arts. These gendered characterizations of hand combat systems were fundamentally tied to larger narratives of national competition and resistance (see Wendy Rouse’s 2015 article “Jiu-Jitsuing Uncle Sam” .

but as the author notes, the situation is often muddied

Shidachi appears to have had little actual familiarity with Western wrestling. It is clear that his discussion was driven by nationalist considerations rather than detailed ethnographic observation. And there is something else that is a bit odd about all of this. While technical skill is certainly an aspect of Western wrestling, gaining physical strength and endurance is also a critical component of Judo training. Shidachi attempted to define all of this as notbeing a part of Judo. Yet a visit to the local university Judo team will reveal a group of very strong, well developed, athletes. Nor is that a recent development. I was recently looking at some photos of Judo players in the Japanese Navy at the start of WWII and any one those guys could have passed as a modern weight lifter. One suspects that the Japanese Navy noticed this as well.

But while the idea of the soft overcoming the hard has already fallen to the level of a cliché, especially when it comes to martial arts, and mixed with political ideas, should we ignore it as a way of being in the world? I’d say not. It does point to a truth.

Anyone with any familiarity in martial arts is aware of the feeling of having to ‘muscle’ a technique to make it work, as opposed to executing a clean technique based on good leverage. This points towards what I think these chapters of the Tao Te Ching are talking about.

When it comes to Tai Chi one of the hardest things to grasp about the techniques exemplified in the forms is that they shouldn’t necessarily feel powerful to you as you do them. My teacher often uses this phrase: “…if you feel it then they don’t – you want them to feel it, not you“.

If you can give up the need to control and struggle with a situation, then you can relax and access your own inner power. See what acliché that statement sounds like already? It sounds like one to me as I wrote it, but I guess all cliches were probably based on something real, otherwise, they wouldn’t be a cliché.

In Chinese martial arts that sweet spot between doing and not doing (to bastardize some more Taoist terminology) is called Jin. I’ve written a bit about that before:

Jin in Chinese martial arts (and tennis)