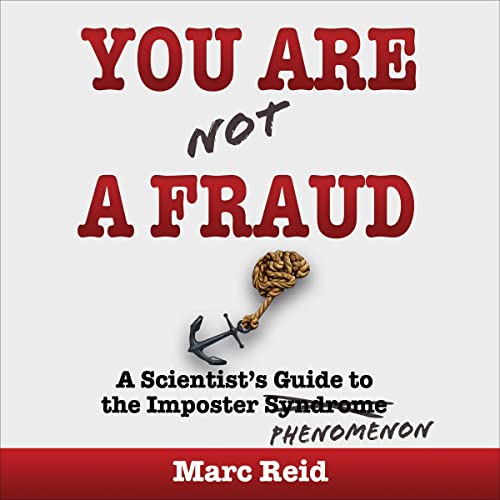

I’ve been delving into the depths of imposter syndrome and how it relates to martial arts recently. It started when we had Dr Marc Reid of the Reid Indeed podcast and author of “You are not a fraud” on our Heretics podcast last week.

It was a great interview – one of the best episodes we’ve done, I thought. I’d never really thought much about Imposter Syndrome before, but once we had Marc booked as a guest I realised it was a great opportunity to discuss how it relates to martial arts, and that it was actually something that has been on my mind for quite a while.

I think every martial artist must deal with imposter syndrome to some extent. But, as I learned in the podcast, having a little bit of imposter syndrome can actually be a good thing for your development, as it allows you room to grow and stops you thinking you know everything.

The question, “am I really good at this?” Is one that I think plagues all long-term martial artists… after they get good enough at their art that it becomes a question worth asking, of course.

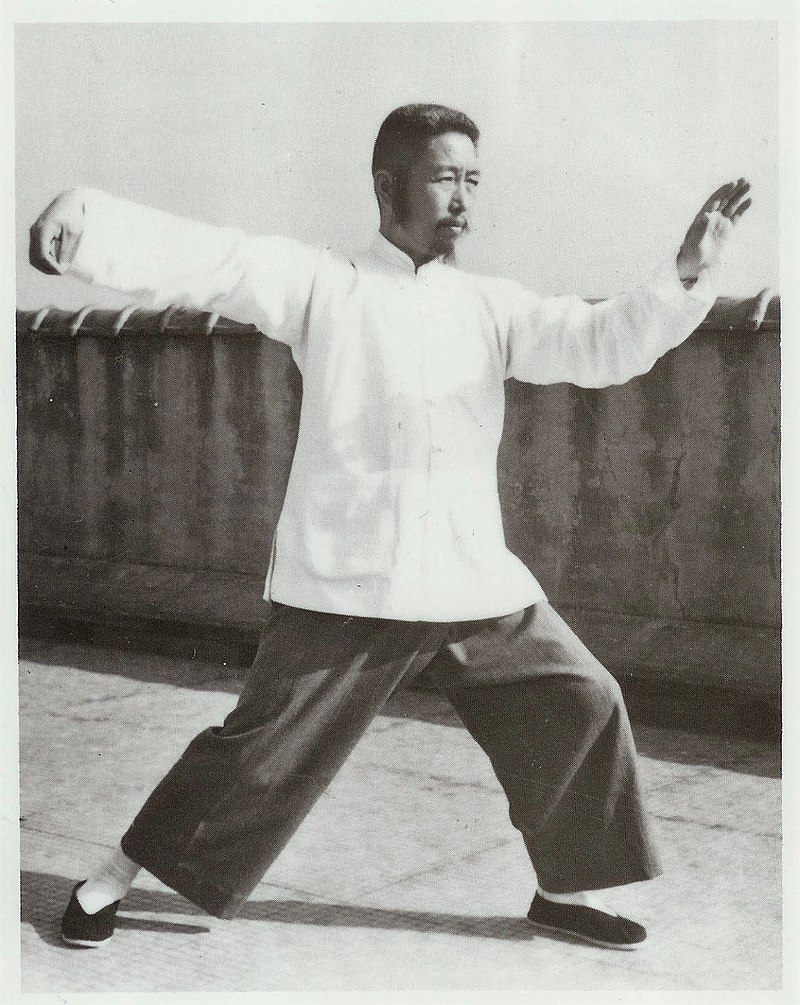

One thing that’s quite common to see, especially in Chinese marital arts, (where entering competition or testing against resistance is often frowned upon, as it prevents “lethal” techniques being used) is the ‘master’ demonstrating only on his own students who are literally throwing themselves on to the ground for him, at the lightest of touches. I mean, we’ve all seen Aikido demonstrations, right? I often wonder what’s going through the mind of the ‘master’ in those situations, because they must know they’re a fraud, yet they carry on as if they are unbeatable. But I guess that so long as they never out themselves in a situation where they will encounter any real resistance they will be! In a way, it’s almost like the performance of a magic show, and the students are subtly required to play along by the group dynamic by the magician performing his tricks.

Sadly, we’ve all seen the videos of what happens when these ‘masters’ try their tricks on tough people from outside their group who are not going to play along. Of course, not all Chinese marital artists (or Aikido schools) are like this. I need to say that now because otherwise you just get tarred with the “hater” brush.

One of the things that attracted me to BJJ initially was the live sparring. You get to ‘test’ your ability every class, since half the class is usually live sparring. You can see exactly how good you are compared to other people. I love that real, live, feedback – I guess you could call it direct contact with nature because you are experiencing what happens against a live person who is not just going to play along in the same way that somebody who thought they were good at running could try a long distance, or a weight lifter can try lifting a heavy weight.

BJJ sparring has a limited rule set, yes, there’s no punching or kicking, for example, but within the confines of that ruleset you can really go 100% and see what happens. As a tool to keep your ego in check, I think it’s invaluable. (Not that you want to be going 100% every roll, of course).

But even within BJJ there are opportunities for the imposter syndrome to sneak in in other, more subtle, ways. There are belts that get awarded as you progress, and to this day it’s rare for me to find somebody who has just been promoted who thinks they are worthy of the belt they’ve just been given – everybody feels a little bit like a fraud, even with all the live sparring going on, or even entering competitions and testing yourself against people of the same belt rank and age from other schools. Competing is time consuming and expensive and not everybody competes and you can start to worry that you are only good within the confines of your own school.

Bruce Lee had a lot to say about belts “Belts are only good for holding up your pants” was, I think, one of his. I remember that and “boards don’t hit back” being another classic Lee quote from Enter the Dragon. But it’s an interesting perspective – all this worrying about belts and being an imposter is completely in your own head – in realty, belts don’t matter, all that matters is what you can do.

That’s one of the reasons I make an effort to get out and train with other BJJ people whenever the opportunity arises, like at the recent 40+ Grappling event I went to. I get to mix with a range of belt levels, all from different schools.

Getting out there and mixing it up can certainly do wonders for quashing any imposter syndrome that might be building up in your head. Even if you don’t necessarily ‘win’ all the time, I find it really rare that any BJJ practitioner isn’t up to the level their belt suggests. BJJ belts tend to only get awarded when an instructor thinks you’re ready for it. Trust your instructor. They’re usually right.

There are also plenty of complete frauds in martial arts who are clearly running some sort of con. Fake black belts in BJJ tend to get found out pretty quickly, but the marital arts is a very unregulated profession and anybody can set up shop at any time, claiming whatever qualifications they like. If any serious martial arts practitioner compares themselves to these genuine imposters it’s pretty easy to realise that you’re not the imposter you might think you are.

The opposite of the impostor syndrome of course is the over confidence of the person who is slightly, or perhaps very, deluded about their own abilities. I’m sure we all know people who talk a good game (especially on the Internet), but if you ever see them move or demonstrate something they can’t hide their actual true ability, or lack of it.

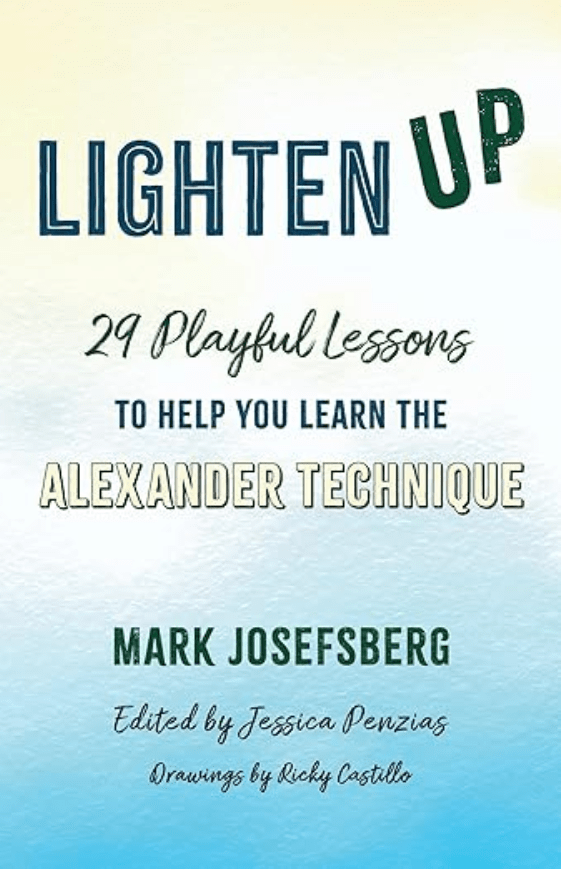

So, maybe feeling like a bit of an imposter sometimes is actually good for you, and stops your ego taking control and turning you into one of these untouchable master types. I notice all the time when I’m teaching that people will try very hard to put you on a pedestal. To be honest it happened much more often when I was teaching Tai Chi compared to teaching BJJ, but it still happens. I’m very aware of people’s attempts to turn me, the teacher, or me the higher belt into some sort of idol and I try and stop it happening before it starts. A good start is to reject people calling you special Chinese titles like Sifu or Laoshi, (I’m not Chinese) in Tai Chi and in BJJ it’s a custom to call your teacher a Professor (Portuguese for “coach”), but I try and discourage that where I can. I’m happy with just my name. That’s my personal choice, and not a judgement on other people who may have very good reasons for using those titles. They can do what they want.