One of my projects for 2024 is to start teaching Tai Chi again. I’m looking forward to the new challenge, and a new bunch of students. My class details are here. Hope to see you?

tai chi

Tai Chi Applications: Needle at Sea Bottom, Fan through back, White Snake Spits out Tongue + Torso-Flung punch

My friend Sifu Donald Kerr of Spinning Dragon Tao has been producing some great videos recently featuring my teacher, Sifu Rand, demonstrating Tai Chi applications from our version of the Yang form. If you’re interested, I’ve written an article about the full lineage of that form before, but a quick summary is that it’s the Yang form from before Yang Cheng-Fu’s modifications, but with some input from Sun Lu Tang, so it’s a bit of a hybrid.

Needle at Bottom of the Sea, Shoulder through the arm and White Snake Spits Out Tongue.

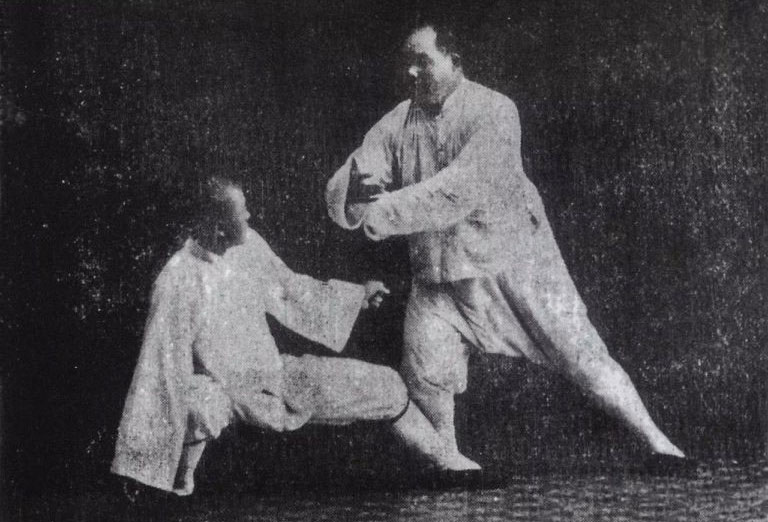

I thought I’d do some posts as new videos become available comparing the videos to the historical books on the style that contain photographs.

There are a couple of historical books available that catalogue the long form in quite some detail. The first is the 1938 book by Gu Ru Zhang, then there’s the 1952 book by his student Long Zi Xiang, both of which have been kindly translated by Paul Brennan.

I’m using the 1952 book by Long Zi Xiang here, as the photos are of a higher quality. The English versions of the move names will always be slightly different, depending on the translator. Brennan translates these moves I’m looking at today, in order, as Needle under the sea (海底針), Shoulder through the arm (肩通臂) and White Snake shoots out its tongue (白蛇吐信).

In our school we use the names Needle at Sea Bottom, Fan through back and we don’t have a name for what Long is calling White Snake… it’s just part of Fan through back.

The application Long describes for Needle at Sea Bottom is, “If the opponent punches to my chest, I grab his wrist and press down, making his power drop downward.” It’s a pretty short explanation, but it does seem to match the modern day demonstration quite well:

For Shoulder through the arm, Long says, “If an opponent strikes from in front of me, I use my right hand to prop up his fist so that he cannot lower it, at the same time using my left hand to obstruct his waist and send him outward, causing him to topple over.”

Again, that’s a pretty good explanation of what happens in that video.

Long has one more application for the part of the form we don’t name - White Snake… – which is a simple block and strike to a different opponent, “If an opponent punches to my waist, I then press down with my right hand while my body moves back so that his punch lands on nothing, and then I use my right [left] fist to strike to his face.“

We seem more interested in the next move, which is “Torso-Flung Punch” (撇身捶) according to Brennan’s translation. We call this move “Chop opponent with fist“, and it’s the natural conclusion to the previous moves, so I’ll add it on here:

The explanation for the application is: “If an opponent attacks me with a [left] punch and [right] kick at the same time, I then withdraw my right leg, causing his kick to land on nothing, my right hand pressing down his fist. Then my left palm pushes down on his arm, and my right hand turns over from inside with a strike to his face.” Which ties in very well with the video showing the application by Sifu Rand:

Martial Arts Studies Conference 2024

So, I’m going to the Martial Arts Studies Conference, June 4-6, 2024! It’s in Cardiff and there’s a video explaining exactly where:

My friend, Professor Paul Bowman, waffles on in that video about how to find a building that’s simply opposite the train station…. but I think all the vital info is in there on its price and location, except what the conference contains. I suppose that’s because the list of speakers is still being finalised, but I can tell you from my last visit to one of these that they are really interesting and the range of topics is always challenging, thought provoking and fascinating, and the speakers are absorbing and entertaining to the max. Last time I went I had such a good time, and met a lot of new faces, many of which are still friends to this day.

Are you going? If you are and you want to meet up then let me know. I’m available for Tai Chi push hands, BJJ rolling (in a gi please! There’s a possible open mat situation at a BJJ academy next door), weddings, funerals and evening festivities involving alcohol (hey, it’s my birthday at the same time!), just hit me up.

Paul and I, philosophising in his philosophers’ garden about the

intricacies of the guard.

Tongue behind the two front teeth

If you’ve been doing Tai Chi, meditation or yoga for any length of time you’ll have heard the old adage to ‘put your tongue behind the two front teeth‘. The explanation given for this is usually that it “connects the two meridians that go up the back and down the front of the body called the Ren and Du meridians, creating the micro-cosmic orbit”.

From a Chinese medicine or Taoist perspective the perceived wisdom seems to be that “circulation of the Qi/Breath in Ren Mo and Du Mo is a bit like an electrical circuit. The two ends of the vessels must be connected for there to be an uninterrupted flow.”

Personally, I have my doubts about the whole idea of ‘energy’ or Qi ‘flowing’ around the body. I often think it’s really an ancient aberration of the simple idea of forces moving inside the body. In Chinese martial arts there’s a phrase you often hear – rise, drill, overturn, fall, which matches this circuit in the body with a martial technique. The best example of which is Pi Quan from Xing Yi, during which forces in the body (jin) rise up and then come crashing down into a strike.

Strength and balance

However, it’s not just Chinese medicine that recommends this tongue position. I’ve recently discovered that there are a lot of Western sources advocating the same tongue position. For example, Colgate toothpaste has an article about correct tongue position on its website that recommends the exact same thing – the tongue resting on the upper palette behind the two front teeth. The article links to a study in Radiology and Oncology called “Three-dimensional Ultrasound Evaluation of Tongue Posture and Its Impact on Articulation Disorders in Preschool Children with Anterior Open Bite“, which notes that “children with poor tongue posture were reported to have a higher incidence of anterior open bite, a type of malocclusion where the front teeth don’t touch when the mouth is shut. This may be because the tongue puts pressure on the teeth which can shift their position over time.” (Colgate).

In this article from Healthline, Dr. Ron Baise, dentist of 92 Dental in London explains “Your tongue should be touching the roof of your mouth when resting… It should not be touching the bottom of your mouth. The front tip of your tongue should be about half an inch higher than your front teeth.“

While dentists may be aware of the benefits of good tongue position for your teeth and preventing problems with your speech, or mouth breathing from occurring, some exercise enthusiasts are going further and claiming that proper tongue position actually increases your strength and balance, something that is undoubtedly important for martial arts, like Xing Yi.

Now, I’m as aware as the next Tai Chi blogger that cherry picking studies that confirm your beliefs (and presumably ignoring everything that doesn’t) is a bit of a red flag. However, the idea that your tongue position effects strength and balance makes more sense to me than imaginary energy channels (Du/Ren) that may, or may not, exist in real life.

I remain slightly skeptical about the whole issue, however, my tongue does naturally rest behind my two front teeth on the upper pallet of my mouth… I can feel it there now as I write this. Was it always there? Or have I turned this into my natural position thanks to starting Tai Chi in my 20s?… I don’t know. All I can say is that it feels comfortable, and if my Ren and Du channels are connecting because of it, and my strength and vision is better because of it then…. so much the better.

How most people get Tai Chi breathing wrong

“Stop doing the wrong thing and the right thing does itself.”

– F. Mathias Alexander.

Breathing has become a hot topic these days. There’s Wimm Hoff with his patented breathing methods for overcoming extreme cold all over TV and YouTube, breathing classes have sprung up in every town where you can go to where you spend an hour focusing on your breath (just type in the town you live in an ‘breathing classes’ into Google and I bet you find something), and of course, there still are all sorts breathing methods you can find out there in yoga, tai chi and qigong classes.

Often in Tai Chi we’re told that we should be performing abdominal breathing, or ‘Taoist breathing‘ – so, as you breathe-in the abdomen should expand and as you breathe out, the abdomen should contract*. We equate this abdominal breathing with deep breathing – almost as if the more we can ‘fill’ our abdomen with air, the deeper and better the breathing will be – and think that it therefore must be healthy. (* there is also reverse breathing, but that’s another topic).

How to breathe

I recently started reading the excellent book ‘How to breathe’ by Richard Bennan, which has made me reconsider the way I’ve been approaching breathing in Tai Chi.

Firstly, let’s start with the basics. It’s worth remembering where your lungs are. They are behind the ribs and reach up higher than the collar bones on each side. Look at the picture below and you’ll be surprised by how far up the lungs go. So, when you expand your belly on an in-breath the air isn’t going down into your belly – it all stays in your upper torso. Of course, that might already be obvious to you, but you’d be surprised how many people think their belly is filling with air when they breathe in! It’s not.

When you practice ‘belly breathing’ what you should be doing is expanding the whole torso on an in-breath, and it’s this expansion of the lungs and the dropping of the diaphragm that pushes the abdomen down and outwards (on all sides, not just the front). If you start to try to use your abdomen muscles to lead the process, or force-ably expand or contract the belly as you breathe in and out then you are just adding tension to the whole process, which is the exact opposite of what you want. There should be as little tension as possible for efficient breathing. Trust the process – it will work on its own.

So, with me now, try an in-breath and focus on the lungs themselves filling up and expanding and this wave of expansion being the motivating force for expanding the belly. It doesn’t really happen in a step by step way either – everything expands at once. So, don’t try to fill one section of the torso, then another, that is also just adding tension. Equally, don’t try and keep the ribs still. They are designed to expand and contract with the lungs. If you try and keep them still, then, you guessed it… You’re just adding more tension.

Once you can visualise where your lungs are, (and how far up they go above the collar bones), then just focus on letting them expand freely, and stop interfering with the breathing process. Less is often more.

You might also like to think about the posture requirements of Tai Chi and what effect these might be having on your breathing. We often hear words like “round the shoulders”, “lift the back” and “hollow the chest” in Tai Chi. Think for a minute about what effect those directions, if followed literally, might be having on your breathing. Do you think they are beneficial or harmful? It’s something to consider anyway.

Breathing should feel amazing. It should feel smooth, natural and healing. And it will, if you stop interfering with it.

* I think reverse breathing is a deliberate hack to the body’s natural way of breathing, but I don’t think people should be attempting it before they’ve got better at breathing in a natural way first. If you are already breathing in an unnatural way, and then you try and add on something else, well, it doesn’t take a genius to realise that you’re headed for long term problems.

Making up your own forms – it’s not as easy as you think

I had an interesting comment on my last post that made me think about the whole idea of making up your own forms (or Tao Lu) – in Tai Chi, Xing Yi, or whatever.

I’ve tried to do this over the course of several years and I’ve come to a few conclusions about it, which I’ll elaborate on here. Firstly, it’s hard. Making up new forms is not as easy as you think. But secondly, it depends what martial art you are making up a form in.

If your martial art has forms that are constructed like lego bricks that can be slotted together in any order and still seem to work then it’s pretty simple to concoct a new form. Xing Yi is a good example of a martial art that has this quality. I was always told never to call Xing Yi tao lu by the English name “forms” because the correct term was lian huan which means “linking sequence” for this very reason.

The idea, (in our Xing Yi at any rate), is that all the links you learn are just examples, and you need to be constantly moving towards being able to spontaneously vary them as required, and then ultimately spontaneously create them. This idea has become heretical in the modern Xing Yi world to a large extent because modern Xing Yi has lost a lot of this spontaneous feel it used to (I admit that’s a subjective point) have, and things have become set in stone – forms that were once supposed to be fluid and flexible have become fixed and rigid. Forms of famous masters from the past now tend to be fixed forever. When words like “orthodox” start appearing to describe something you know it’s already dead, or on the way to dying.

But of course, anybody can make up a form, but is it any good? That’s a different matter. And it usually depends on the person doing it, not the moves themselves. With Xing Yi animals you can also ask the question – can I see the character of the animal being used coming out through the moves?

With Tai Chi I find it a lot harder to make up a form. Tai Chi’s approach to a form is quite different to Xing Yi, or other Kung Fu styles. The Tai Chi form tends to be a highly crafted piece of work that has been honed to perfection over many years. It is fixed because you need to be able to forget about the moves and concentrate more on what’s inside. It helps to do that if you don’t have to worry about what’s coming next because you’ve done it so many times that you can let go of that part of your brain and let it be aware of other things.

Tai Chi forms tend to start and finish in the same place for this reason. Usually, anyway. While long forms don’t tend to be balanced on left and right, a lot of the more modern, shorter forms make more of an effort to balance left and right movements.

If you understand Tai Chi and how to ‘pull’ or direct the limbs from the dantien movement then, sure you can make up your own Tai Chi forms, however, there is almost zero history of doing this in Tai Chi circles and it’s not really encouraged. I think this is because Tai Chi has push hands, which can be used as a kind of free-form expression of Tai Chi, completely away from the form and in contact with a partner to give you something to respond to, which is the whole strategy of Tai Chi Chuan, at least according to the Tai Chi Classics it is. To ‘give up yourself and follow the other’ you have to be spontaneous. There’s no other choice!

So, to conclude. I think that’s it’s in its application where the spirit of improvisation and spontaneity can be found in Tai Chi, not in the forms. I don’t think Tai Chi is particularly concerned with creating endless variations of forms and patterns like Xing Yi is, at all. Xing Yi, having a weapons starting point, doesn’t use this hands-on feeling and sensitivity to get started with spontaneity. Instead, it likes to create patterns, then vary them endlessly. Of course, you work with a partner when required, but it’s a different approach. Which is all quite natural, as these are two different martial arts, created by entirely different groups of people in a different locations and time periods.

You might like our Heretics history of Tai Chi and Xing Yi for more on that.

Tai Chi on the minute, every minute

A friend shared a post recently about an interesting way of exercising called On the Minute, Every Minute. All you need to do is a number of reps of an exercise on the minute, every minute. The suggested start point in the article is 15 push ups, then 20 squats, then 20 plank jacks. That would take 3 minutes, so you just keep going 6 more times, up to 18 minutes. I quite like the idea because it’s simple, and simple is doable.

Then I started to think how you could apply the same OTMEM method to Tai Chi… Here’s one suggestion: One move every minute then hold until the next minute comes around. I think a short form has around 50-60 moves, so would take roughly an hour to complete like this. It depends what you count as a move. That’s basically an hour of stance training, which would be quite challenging. One for New Year’s Day perhaps? I’m going to give it a go, so let me know in the comments if you are going to join me.

And of course, if you want to push it further you could always up it to every two minutes!

A quick Tai Chi fix anybody can try: Tracking with the eyes

To some Tai Chi people it’s important to know where the eyes are looking when doing a Tai Chi form for slightly esoteric reasons: “your eyes lead your intention and your intention leads your chi.” But I think we can come up with reasons for using the eyes in Tai Chi that require no mention of intention (yi) or chi.

Try this: Sit comfortably. Turn your head slowly to the side, back to the middle then the other side. It’s a typical neck stretching exercise that you’ll find done at the start of your typical Kung Fu, Tai Chi, or Yoga class. It’s good for your neck, but there’s nothing particularly special about it.

Now try this: Instead of just turning your head to the side, actively look to the side. Lead the movement with your eyes looking to the side. Now compare the feeling of doing that to the feeling of just turning your head to the side.

If you’re anything like me you’ll find the experience quite different. When you are looking to the side for a reason your whole body co-ordinates better, not to mention, I think you can turn your head a bit further too. I’m sure there is a scientific word for this purpose driven movement, but I don’t know it.

Think of an owl, when it turns its head to look at something interesting that might potentially be prey – the eyes are always locked in.

When doing the Tai Chi form, try actively looking with your eyes and turning your head in the direction you are going. Hopefully you’ll notice the different in the quality and coordination of your overall movement.

New podcast! Richard Johnson on Chen Style Practical Method

This month’s podcast guest is Richard Johnson a long-time student of Joseph Chen of Chen Style Practical Method.

As well as a Tai Chi practitioner and teacher, Richard is a full time movement coach working with athletes, so he brings an appreciation of athletic movement to his views on Tai Chi.

In our discussion Richard delves deeply into the internal workings of the Chen Style Practical Method and we talk a lot some interesting movement principles based around rotation. We also talk about how the Practical Method is different to the Chen Village style of Tai Chi.

Enjoy the podcast. You can get in touch with Richard using his email address trukinetix at gmail.com

The number 1 mistake people make in Tai Chi push hands and how to fix it

I got to meet up with a local Tai Chi instructor recently, and it was a good chance for me to do some hands-on work in push hands. One of the things working with somebody else at Tai Chi, as opposed to the endless solo practice that mainly makes up the art, brings up is the question of range.

Range is an interesting one in Tai Chi. You actually need to be in really close for Tai Chi to work. I think this is one of the things that has been forgotten along with the martial aspects of the art. I very rarely find another Tai Chi person who is comfortable working at the correct range.

How to fix your range

To get the correct range your front foot should be one fists-width apart from your opponents foot on the horizontal axis and your front toes should be roughly matching the back of heel. His front toes are then roughly matching your heel. (Look at the foot position in the photo).

This distance feels uncomfortably close to do any sort of combat actions to most people, however, this is where Tai Chi lives. At this range you will need to use subtle movements of the kua and rotation of the body to neutralise your opponent’s force, and it takes some practice. You also need to make use of Ting – or “listening” because you are definitely within punching range here, but from here you can go even closer (body to body) and turn it into wrestling if so desired, which will protect you from punches.

At the correct distance the Tai Chi techniques will work. When you are further out, they won’t work so well at all. So, this is where you should be when practicing push hands.

When it comes to actually fighting, I’m not suggesting you should “hand around” in this range, because that will just get you clipped. However, you do need to move into this range to do all the good stuff that the Tai Chi Classics talk about – controlling your opponent, knowing him before he knows you, etc. I think a lot of the time that Tai Chi fighting is described as “bad kick boxing” it’s because of the range being used. People stay too far out and pot shots at each other. Kick boxing is perfect for this range.

More of my writing on push hands: