What’s in a name? When it comes to tai chi chuan (taijiquan), then the answer is… quite a lot.

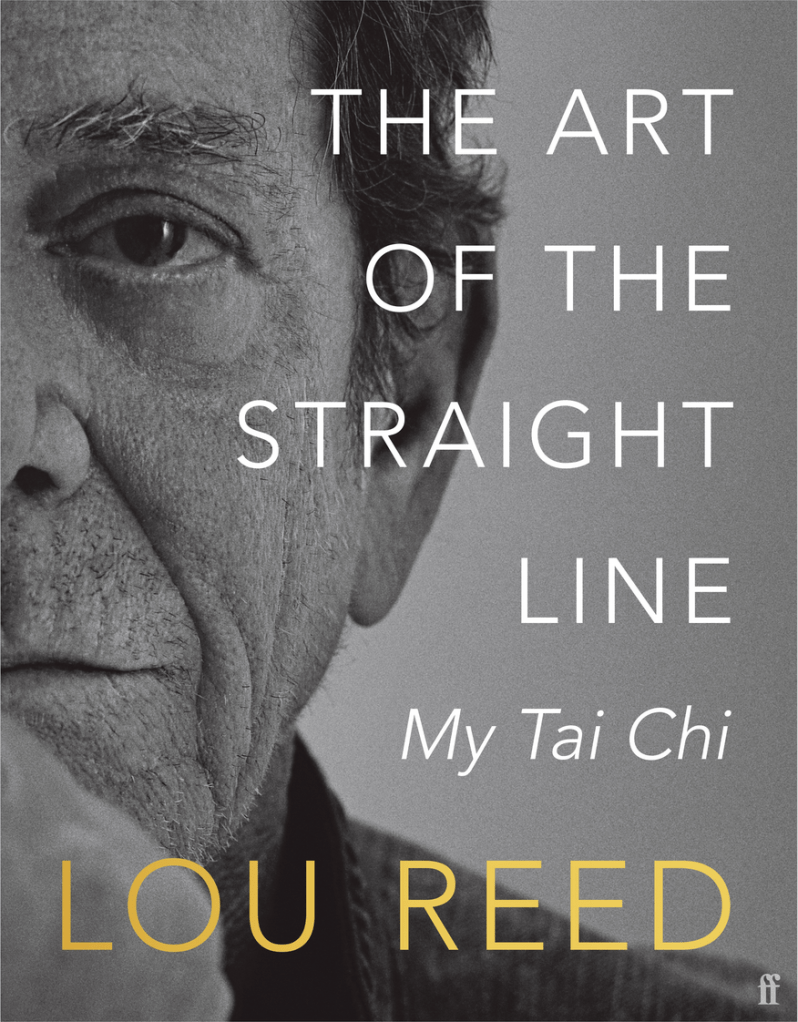

Firstly, there’s the issue of how you write it. Occasionally, you will see an attempt to guess at the spelling of the name that makes the mind boggle, such as an email asking if somebody can come to your “thai chee” class, but usually it’s some variation of “tai chi” or “taiji”.

Tai chi was first romaised into English using the Wade–Giles system as “tʻai chi chʻüan”. But English speakers soon abbreviated it to “tʻai chi” and dropped the mark of aspiration. Nowadays, in the UK at least, we tend to use “tai chi” and forget about the “chuan”. Perhaps a better translation would be “tai chi boxing”, but this goes against the image of the art, which is usually practiced as a health exercise, so that’s never going to catch on. There really isn’t much “boxing” going on in most tai chi classes.

Then there’s he newer pinyin romanisation system, which has replaced Wade–Giles as the most popular system for romanizing Chinese. In pinyin, tai chi is written taijiquan. It’s popular to use taiji or taijiquan in English now to also remove any colonialist connotations of the term from a bygone era.

I get that, but I think the written phrase tai chi has slipped so far into the general populations consciousness that a lot of people have no idea what you’re talking about if you write taijiquan. I use tai chi myself.

Step back into the Qing dynasty

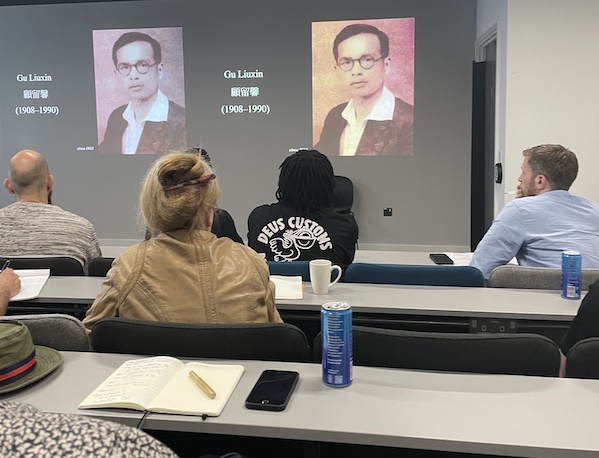

Then there’s the issue of when the art was given the name tai chi boxing. Tai chi emerged into public life in the royal court during the Qing dynasty, yet it wasn’t freely called tai chi until after the dynasty ended. If you try and find a written occurrence of the name published before 1912 you’ll draw a blank. There are certainly written documents that claim to be from years earlier that contain the name “tai chi boxing” yet not a single one of them was made public or published before 1912. What happened in 1912? The Qing dynasty collapsed and the new Republican era began.

My best guess as for the reason that this is the case is that Hong Taiji (1592 – 1643), the founding emperor of the Qing dynasty had adopted the name “Taiji”. It’s unclear if this was his personal name or a title, but there was certainly a taboo around using that name because it belonged to an emperor. It therefore became impossible for a marital art to be called “tai chi boxing” without breaking that taboo and suffering the (presumably harsh) consequences. However, once the Qing dynasty fell, the name was back on the market. (Credit to my friend Daniel Mroz for bringing this to my attention).

The taiji symbol

Then there’s the meaning of the name. The name taiji has obvious connections to the philosophical concept of the taiji symbol – the circle with the two fishes representing yin and yang and their constant interchangeable position. One state increase till it exhausts itself leading to the other in an infinite loop.

In Yang style tai chi lineages, the art has long been associated with Taoist ideas, which the taiji symbol is representative of. Chen style seems less Taoist in origin, however, the concept of taiji is a universal symbol, and used throughout all of Chinese thought.

The name taiji can be translated as “supreme ultimate”, which has lead many to conclude that tai chi boxing must have got the name because it was the boxing system par excellence of the Chinese martial arts scene. It is literally, the best! If only!

I wish that was true, but I think it’s just a common misunderstanding, which is perhaps played on as a marketing device in modern times. I mean, who wouldn’t want to be learning the supreme ultimate boxing system, right?

The concept of being a supreme ultimate is more to do with supremely different positions being harmonised. Extreme yang and extreme yin. Polar opposites that work together and find harmony. That’s the real meaning.

In Tai Chi your body moves through position after position – we call these ‘postures’ usually – in the transition between them the body will open and close in a repetitious cycle. Once yang (open) is exhausted the body will move to yin (close) once you’ve reached the extreme position of yin, you move back to yang again, and so on.

The opening and closing is a whole body action. So, you are literally enacting the taiji diagram with your body.

That’s the general idea. Of course, you can break down your body into sections and look at how each one of those opens and closes, there is seemingly no end to the level of detail you can drill down to, but on a basic level your body is always moving from yin to yang and back again, which is the reason for the name of the art – tai chi chuan.