And why you should probably keep doing it anyway

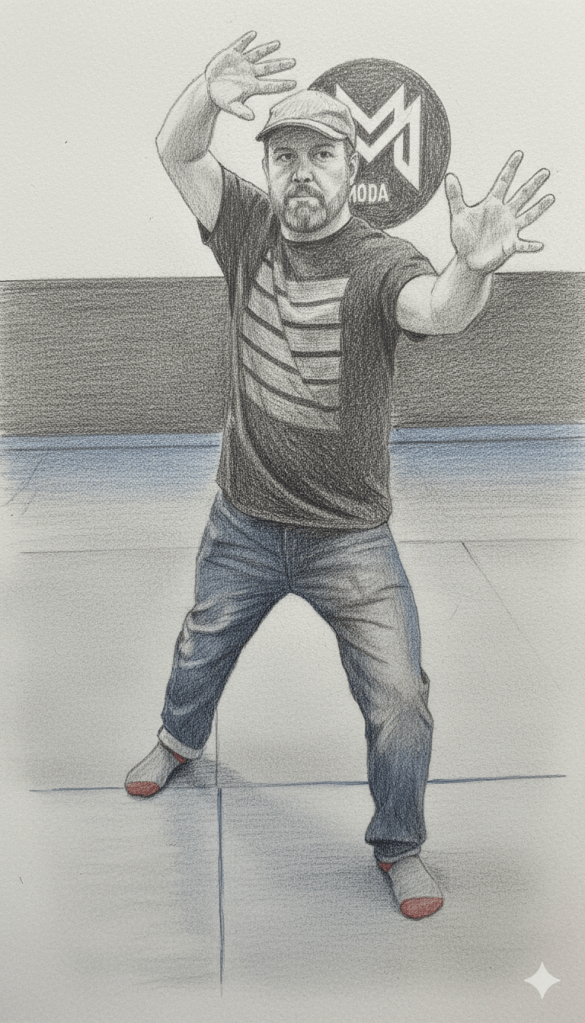

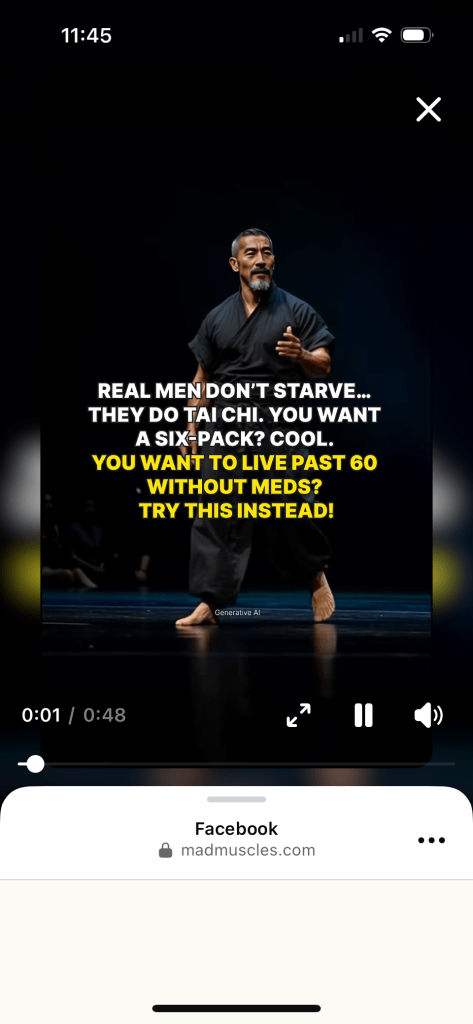

Tai Chi has always felt like it’s very good for me — for the mind, the breath, the joints, for my overall functioning as a human being — but I’ve never really considered it a weight-loss tool. That’s despite the rash of frankly hilarious ads currently clogging up social media, bizarrely presenting Tai Chi as the secret to giving men over 50 a six-pack.

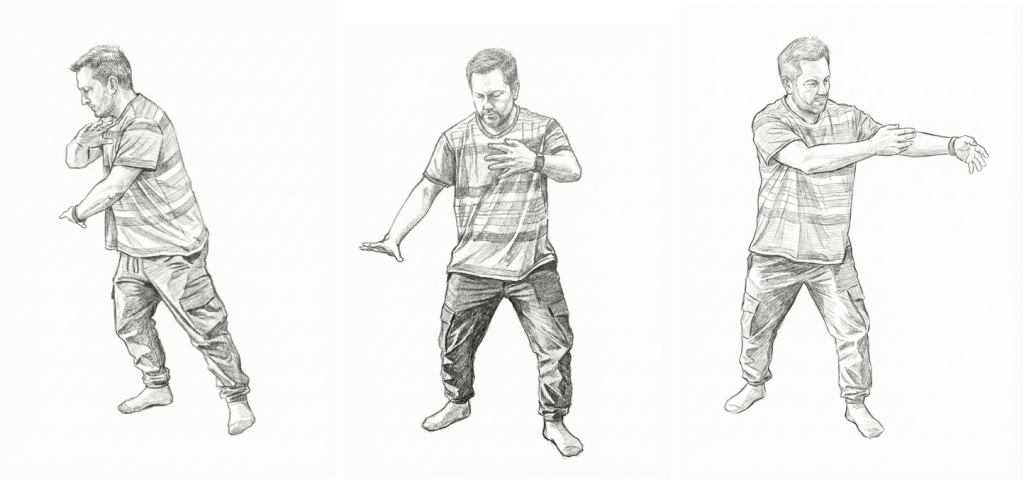

What’s even more galling is that if you actually look at the “Tai Chi” weight-loss exercises these products are trying to sell, they’re not Tai Chi at all. They’re what could most generously be described as basic warm-up movements — and the ripped old men demonstrating them are very obviously AI-generated.

Exercise of any kind is beneficial for health, but Tai Chi has never been particularly associated with weight loss. And now, inconveniently for the entire fitness industry, the idea of exercise as a reliable weight-loss tool has just taken a kick in the teeth courtesy of a recent New Scientist article, which argues that exercise, while very good for you, may not lead to weight loss as much as we’ve been led to believe.

According to the article, the basic problem is compensation. When you exercise more, your body simply burns less energy elsewhere to make up for it — and this effect can be even stronger if you’re also dieting.

As the article puts it:

“Exercise is tremendously beneficial for our health in many ways, but it’s not that effective when it comes to losing weight — and now we have the best evidence yet explaining why this is.

People who start to exercise more burn extra calories. Yet they don’t lose nearly as much weight as would be expected based on the extra calories burned. Now, an analysis of 14 trials in people has revealed that our bodies compensate by burning less energy for other things.” – New Scientist

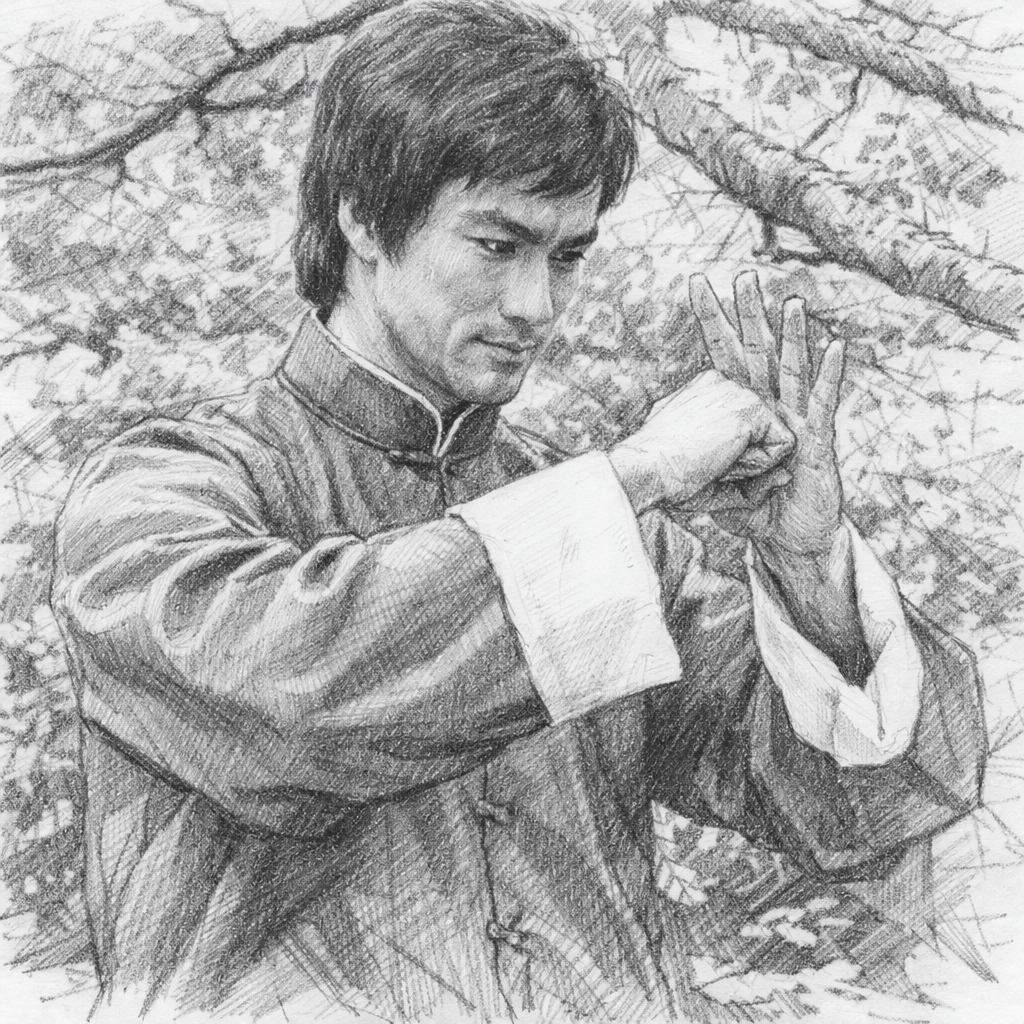

Seen in that light, it makes far more sense to view Chinese martial arts — Tai Chi included — as tools for improving overall quality of life rather than as weight-loss hacks. That includes balance, coordination, joint health, breathing, mental focus, and, perhaps most importantly, social connection.

Feel the burn

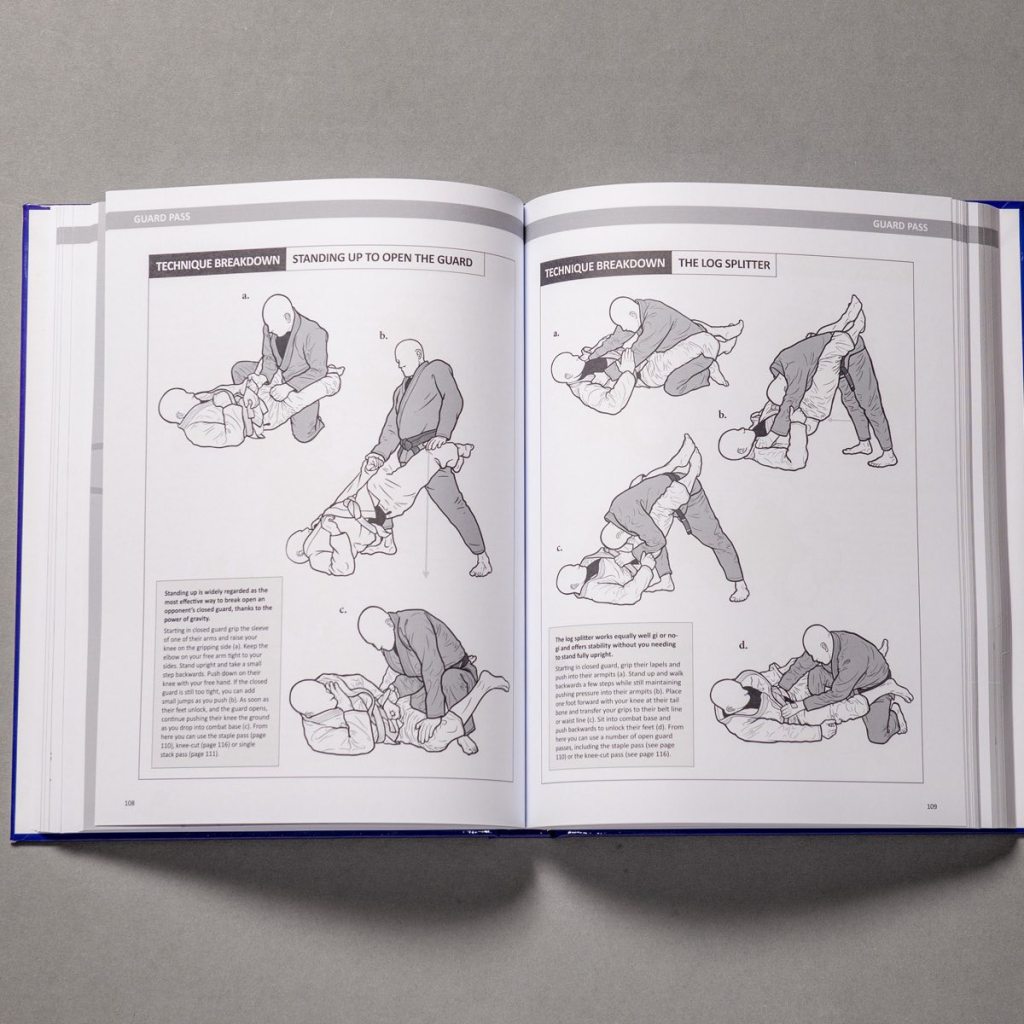

If you’re practicing Tai Chi and want to improve your overall fitness while staying within the Chinese martial arts ecosystem, it’s worth pairing it with something more physically demanding. Styles like Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar, or Praying Mantis, for example, place much greater demands on strength and cardiovascular capacity.

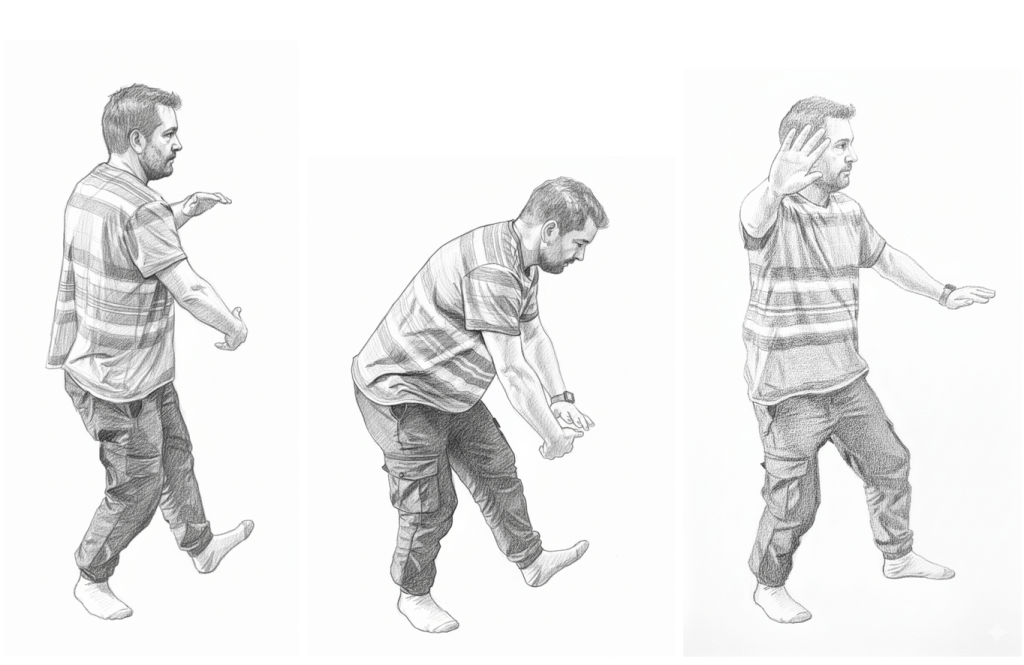

Alternatively, you could lean into the more demanding side of Tai Chi itself — weapons forms, longer routines, or more continuous practice sessions can be surprisingly taxing.

Not all Tai Chi is the same. Most people today practice softer styles, where this advice applies most clearly. Some styles — Chen style in particular — include more vigorous stamping, jumping, and explosive movements, and may not require additional training alongside them.

Either way, common sense still applies. For a well-rounded approach to health, it helps to do something that makes you breathe harder than normal.

Tai Chi doesn’t need to promise abs, calorie burn, or dramatic body transformations to justify its existence. Its value lies elsewhere — in longevity, resilience, awareness, and the quiet accumulation of small benefits over time.

If weight loss happens alongside that, fine. But if it doesn’t, Tai Chi hasn’t failed. It’s simply doing what it has always done best: helping people move better, breathe better, and feel more at home in their bodies — no six-pack required.