Behind the gesture is a code about power, respect, and control

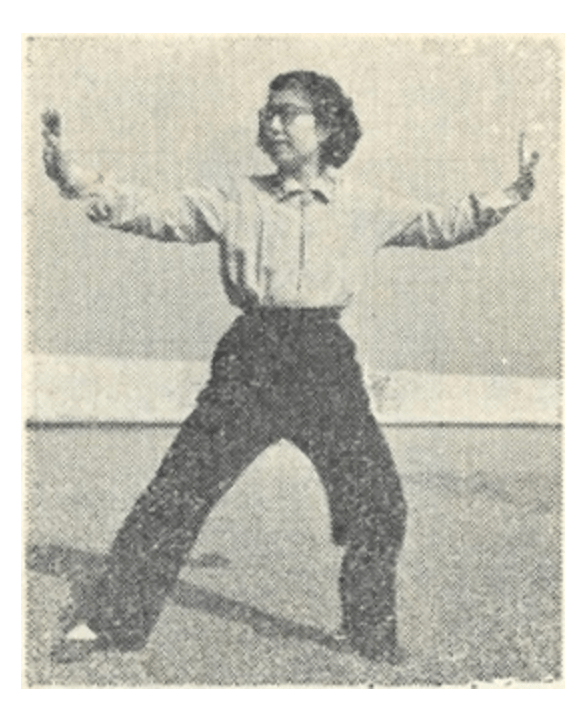

I always finish my Tai Chi class, which takes place in the UK and is taught by me, a British person with no connection to Chinese culture outside of martial arts, with a small Chinese-style salute.

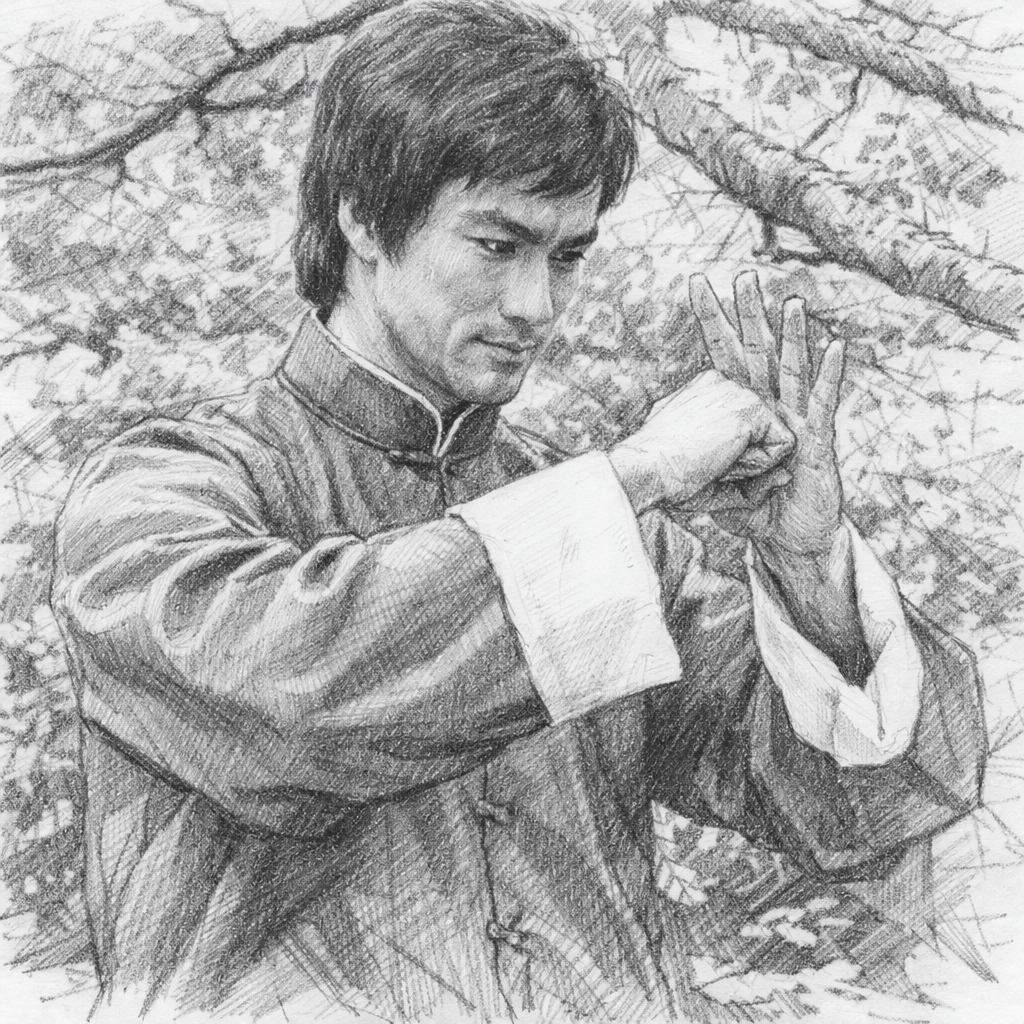

Often called the “sun and moon” salute, it’s a traditional greeting in Chinese martial arts circles. It’s the same one you see Bruce Lee do to his student at the start of Enter the Dragon. But like most things in Chinese martial arts, it has both an obvious meaning and a hidden one. Of course, you don’t need to know the hidden meaning to use it.

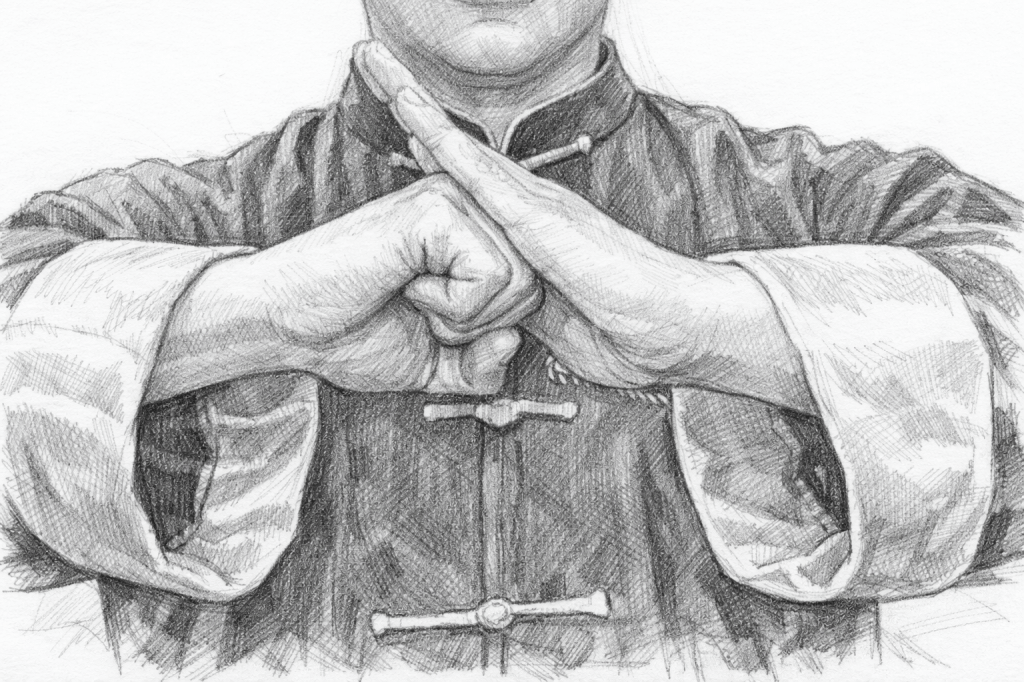

In Chinese, the salute is called bàoquán lǐ, which roughly translates as “fist-wrapping rite.” Your right hand forms a fist — the “sun” — and your left hand presses flat against it — the “moon.” You stand straight, feet together. It’s accompanied by a short, respectful nod of the head rather than a deep formal bow, while maintaining eye contact.

Sometimes the fingers are folded instead. This seems to be a softer, less formal greeting (and it’s the one I usually use). This variation is often called gōngshǒu lǐ (“cupped hands greeting”) and is traditionally gendered — the closed fist is the right fist for men and the left fist for women.

It’s worth noting that this is far from the only hand position used for greeting across China’s long history, particularly within religious traditions.

Why do it?

The bàoquán lǐ isn’t a tradition added to Chinese martial arts — it’s a remnant of a moral code that existed before they were formally named.

At a basic level, the fist represents martial skill or strength, while the palm represents civility, restraint, and wisdom. The palm covering the fist symbolizes martial power governed by virtue or, put simply: I can fight, but I choose respect and control.

When I do it at the end of class, it’s quick and almost reflexive, sometimes even a little embarrassed. I don’t expect my students to do it back. It’s a brief gesture with a clear purpose: it marks the end of the session and acts as a quiet “thank you” for the work they’ve just done.

When I do it to my kung fu teacher, it carries a different weight. My teacher (who is not Chinese) still greets his own teacher (who was Chinese) with this salute every time they meet, and that tradition was passed on to me. I still greet my teacher this way whenever I see him. Even though it isn’t part of my culture, the meaning is clear when I do it.

In that sense, I suppose I’ve passed on a “light” version of the tradition to my own students by using the salute at the end of class. Even if they don’t return it, it’s something they now recognize. The tradition has softened over time, we don’t use it to greet each other, and honestly, I think it would feel strange if we did.

I’d describe my teacher’s period of training with his teacher as serious, and my own training as semi-serious by comparison. People in modern Tai Chi classes aren’t devoting their lives to this with the all-or-nothing commitment that might have been expected in 1860s China. For most people, it’s a hobby. A social activity. Ideally, people leave class feeling better than when they arrived, or at least like they’ve worked hard and learned something.

Hidden meanings

As with most things in a culture that has existed continuously for thousands of years, meanings tend to come in layers.

The sun and moon are obvious representations of yin and yang, shown here as equal forces held in harmony, suggesting balance rather than dominance.

There’s also a practical dimension. A level of formality in martial arts is useful. What we’re engaging in is potentially dangerous, and maintaining respectful ritual helps reinforce that fact.

(Incidentally, that’s one reason I don’t mind bowing in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu training too. We routinely put our training partners in potentially life-changing situations, and a moment of ritual respect is a good reminder that what we’re doing carries real consequences.)

One of my favorite hidden interpretations, though, comes from Chinese history, specifically the Ming–Qing dynasty transition.

The Ming were the last ethnically Han Chinese ruling dynasty. The Qing were Manchu invaders from the north, and they were deeply unpopular with large parts of the population. Resistance movements emerged almost immediately.

The slogan “Overthrow the Qing, restore the Ming” (反清復明, Fǎn Qīng fù Míng) became a rallying cry for secret societies and rebel groups from the fall of the Ming in 1644 well into the early 20th century.

The bàoquán lǐ salute was reportedly adopted by some of these movements as a covert signal of allegiance. The closed fist was said to represent the character for sun (日), while the open palm represented moon (月). Together, these two characters form 明 (Míng), meaning “bright” or “to illuminate,” and also the name of the fallen dynasty.

Which means that, technically speaking, every time I’ve used this greeting, I’ve been quietly expressing support for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

But no, my Tai Chi class isn’t secretly plotting the restoration of a long-collapsed Chinese dynasty. But I do like the idea that a small, slightly awkward gesture at the end of a community hall class carries echoes of philosophy, rebellion, and restraint. Even if most of the time, it’s really just a polite way of saying: thanks for showing up — see you next week.