Here’s the second episode of my Tai Chi course on mindful Tai Chi movements. This week we take a look at where you power you movements from in the body. Enjoy!

Tai Chi / Taijiquan

My FREE 8-week Tai Chi Notebook course has launched!

Good news! I’ve started filming a short 8-week Tai Chi Notebook course, and you can get it here, for free.

As usual things come together by chance (or maybe a it’s fate) but either way, a friend asked me to show them how to do “this internal stuff“, so I was about to shoot them a simple video on the basics, then I realised that there’s too much to cover in just one video, so I planned out 8. Then I started to get creative and made it look a little bit professional, and the end result is what you’ve got here – a short YouTube course called Pulling earth, pushing heaven.

In week 1 of the course we cover the concept of “maintain and extend”. Each week will focus on a different aspect until we get to the point where you’ve got the basic idea of “Tai Chi movement”. Of course, this is just ‘foot in the door’ stuff, but I’d like to think that after following along for 8 weeks, and doing it every day, you’d at least have the correct foot inside the correct door. Look out for part 2 next week.

Wu Wei – the art of doing without doing

The connections between Tai Chi and Taoism are at once obvious (the Tai Chi symbol is used extensively in Taoism) and also sketchy at best (there is no historical lineage connection).

You see a lot of Taoist priests (or at least Chinese people wearing Taoist priest robes) on Wudang mountain, which has traditionally been associated with Taoism, teaching people Tai Chi, Xing Yi and Bagua (the internal arts) in the lineage of Chang San Feng, the mythical Taoist who is traditionally associated with the origins of Tai Chi Chuan, but whose historical existence seems difficult to prove.

However, how long these modern days Taoists have been there teaching people martial arts I’m not sure. The fact that their ‘ancient’ martial arts look remarkably similar to the modern “wu shu” versions created in Beijing makes them seem highly suspect to me…

But while a direct connection between Taoism and Tai Chi may be difficult to prove, they clearly employ the similar ideas. Take for instance the idea of Wu Wei – the ever elusive “doing without doing” of Taoism.

If you take a look at the Tai Chi Classics you see that while they don’t mention the phrase “Wu Wei” itself the strategy of the art described fits it like a glove. Take the following quotes from the Treatise on Tai Chi Chuan:

It is not excessive or deficient;

it follows a bending, adheres to an extension.When the opponent is hard and I am soft,

it is called tsou [yielding].When I follow the opponent and he becomes backed up,

it is called nian [sticking].If the opponent’s movement is quick,

then quickly respond;

if his movement is slow,

then follow slowly.

It seems Taoism is having something of a resurgence, as this article reveals, as a philosophy for dealing with the anxiety-inducing modern world. Even the rock star intellectual de jour, Jordan Peterson, is getting in on the act.

From Alan Watts back in the ’60s to Jordan Peterson in the modern age, the Western intellectual has had a recurring fascination with Taoist thought. Particularly with the concepts of Wu Wei and the Tao Te Ching. In fact, the book that first got me interested in Tai Chi years ago was The Tao of Pooh by Benjamin Hoff.

I think all this interest in Taoism again is generally a good thing. Let’s see where it leads.

The 6 directions and Jin

If we think of ‘basic Jin’ as being the ability to direct the solidity of the ground through the body, from the feet up to the hands, then there are four basic directions we can use this power in.

- Up

- Down

- Away from the body

- Towards the body

And since you can go away from the body and towards the body on both the x and z axis (to the sides and in front and behind), that makes 6 directions in total.

Here’s Mike Sigman explaining the 6 directions and Jin:

January forms challenge!

New Year, new form

Due to a nasty training injury, I’ve had to lay off the “rough stuff” for a while, which means I’ve got more time to spend on forms practice than usual. The latest little project I’ve been amusing myself with is learning the start of a different Taiji form than the one I know.

I’ve picked Chen style, since this is the oldest style, and pretty different to my Yang style form.

It’s often hard to see the connection between Yang and Chen style since they look so different, but as I’ve discovered, if you start to learn the beginning of one after already knowing the other it’s very easy to see how they have the same root. This has already provided lots of insights into my regular form by looking at how Chen style treats familiar movements.

To be clear, I’m just learning the first few moves of the form. Probably I’ll get up to the Crane Spreads Wings move (or whatever they call it in Chen). After that, I think the law of diminishing returns starts to kick in and the time spent working on a new form and remembering it starts to outweigh the benefits you get from practising it. I already know a long form, so I don’t think there’s much to be gained by undergoing the arduous process of learning another one.

This little project has made me think about a few side issues, which I’d like to go over below:

- Learning from video

There’s this unwritten rule in martial arts that learning anything from a video is bad, or so the conventional wisdom goes. Learning from a real person is preferable, but not always practical. If you’ve got enough experience in an area then I think you can learn a lot from video. Also, let’s not forget, that there are videos on YouTube of recognised experts, like Chen Xiao Wang, doing the form, who are doing it a lot better than any local teacher you’ll find.

For instance, here’s the renowned Taijiquan expert Chen Zheng Li doing the Chen Lao Jia Yi Lu form in a nice relaxed pace that’s easy to follow:

Of course, there will be fine details I’ll miss by copying him, but I’m doing this more as an exercise in personal exploration, rather than in trying to get the Chen form perfect. In fact, I’ve already modified one move I felt would work slightly better in a way I’m more familiar with. (I’m a heretic, I know)

2. Distinguishing ‘energy’ from ‘moves’

Taiji uses the four primary directions of Jin – Peng (upwards), Ji (away from the body), Lu (towards the body) and An (downwards) in various combinations. It’s often hard for people to separate this ‘energy’ direction from the physical movements themselves. So, a “ward off” posture is one thing, but the energy that you usually use with it – Peng – is another. Confusingly, Peng is often translated as “ward off”, so the two become conflated. By doing a new form with different moves, you get to see how the same ‘energy’ is used in a different arm shape.

For instance, in Yang style the ‘ward off’ movements tend to have the palm pointing inwards towards the body, while in Chen style, they are pointed outwards, away from the body.

3. Spotting similarities

So, while a Chen form may look very different to a Yang form, once you start thinking in terms of which of the 4 energies you’re using, you start to see the similarities, even if the postures look different.

For example, both forms start with a Peng to the right, a step forward, another Peng forward, a splitting action, then another Peng to the right, then into the Peng, Lu, Ji, Lu, An sequence known in Yang style as “Grasp Birds Tail” in Yang and “Lazily tying coat” then “Six sealing four closing” in Chen style. (Apparently, the Yang naming came from a mistranslation of the original Chen name, but this matters not to me).

(Note: In some performances, of Chen style – like the one above by Chen Zengli, he misses out the “Lu then Ji” move of the sequence. In others, like this one by CXW below, it’s in there. I don’t know why. Personally, I like to put it in, because it connects me to the Yang style I know.)

Doing Peng in a different arm configuration than you’re used to is, frankly, good for your practice, because it helps you break out of the mould a bit, into a freer execution that is not dictated to by the conventions of your particular style.

The New Year Challenge! Do it yourself

I’d like to challenge you to do the same thing in January. If you’re a Chen stylist, then learn the start of the Yang form up to White Crane Spreads Wings. If you’re a Yang stylist, then give the Chen form a go. Alternatively, investigate the opening sequence of Sun, Wu or Wu(Hao) style. Give it a go!

Here’s a video of Yang and Chen forms done side by side that I’ve posted before because it helps show the similarities:

Taoist Baduan Jin (8 section brocade)

This set of eight exercises is a popular Qi Gong exercise in China, probably the most popular. There are hundreds of different variations. This one I particularly like because although the reeling movement she’s doing is hidden to the point of invisibility, the arm movements are being used very obviously to enhance the subtle tensioning from fingers to toes throughout in a way you can see. Very nice.

How silk is actually reeled, by hand, in China

In his chapter on silk reeling, in the book on Chen Style Tai Chi Chuan (1963) (A snip at only 828 pounds on Amazon in the UK!), Shen Jiazhen writes:

…Tai Chi Chuan movements must be in a shape like pulling silk. Pulling silk [from a cocoon] is done by a circular motion, and because it combines pulling straight and circling, naturally it forms a spiraling shape, which is the unification of the opposites of straight and curved. Silk reeling energy or pulling silk energy both refer to this idea. Because in the process of unreeling, extending out and pulling back the four limbs likewise produce a sort of spiraling shape, therefore the boxing manuals say that whether in large, extended movements or compact, small movements, one must absolutely never depart from this type of Tai Chi energy which unites opposites. Once one has trained in this thoroughly, this silk reeling circle tends to become smaller the more one practices, until one gets to the realm where there is a circle but no circle is apparent, at which point it is known only by intent. 1 This is why the third characteristic of Tai Chi Chuan is that it is an exercise which unifies opposites with silk reeling, both forward and backward.

Thanks to Jerry K for the translation. If you’re interested he’s also translated other chapter of the book – like this one on Empty and Full.

With this in mind I thought it would be beneficial to investigate exactly how silk is pulled from a cocoon. The Chinese have cultivated silk worms for more than 5,000 years. Here’s video showing how silk is cultivated today in Shanghai:

Like any industry, silk production has been automated, but you can still see how people did it using a hand reeling machine in some parts of China:

I’m guessing that the initial spiralling action of her hand she uses to get the starter threads off the brush is where the analogy starts to happen with what you’re doing in silk reeling exercises in Tai Chi Chuan? It reminds me of the way you can play with an elastic band in your hand. With 5,000 years of silk production in China I’m pretty sure the hand reeling machines would have existed at the time Chen style was creating these exercises, some 300-odd years ago, but without a machine then you’d have to be doing it with your hands in that manner.

Either way, I don’t think the silk worm gets out of this alive 😦

“The rotation of the waist/pelvic region is like the turning of a wheel on an axle”

I ran (ha!) across this article by Sam Wuest, thanks to the Steve Morris Facebook page. It’s a really interesting look at how Usain Bolt is the fastest man alive despite not conforming to accepted wisdom on running mechanics.

It turns out Mr Bolt makes clever use of waist rotation when he runs, in contrast to the normal admonitions to reduce rotational movement and increase forward and back movement you’ll get from a lot of running coaches. By turning his waist in coordination with the running motion Mr Bolt is creating a longer lever to the floor, and everybody knows that longer levers create more power than shorter levers over the same distance.

There’s a famous line in the Tai Chi Classics that goes “The waist is like the axle and the ch’i is like the wheel“. At one point in the article, Sam Wuest says

“The rotation of the waist/pelvic region is like the turning of a wheel on an axle. The hip joints are rotating around the imaginary centerline of your body parallel to your spine at about the elevation of the sacrum. It is not a perfect rotation, as the free leg hip will come through higher than the support leg’s hip if the lateral chain is firing correctly. Perhaps it would be better described as a rolling rotation. Which brings us to reason #2 of why this piece of technique is important.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Reason #2 is interesting too:

Reason #2: Better Muscle Sequencing/Activation

Often, those that rotate better whilst sprinting will look smooth and relaxed. Their strides won’t just look longer, they’ll look more relaxed. Think of Carl Lewis’ famously effortless stride. This is how we are designed to move – the center moves first, then the extremities follow, much like a whip.

The muscles around the pelvis have high muscle-to-tendon ratios (force producers) while the extremities have relatively much more tendon and elastic structures (force amplifiers). In a correctly aligned body, a small movement of the waist can produce large amounts of force elsewhere in the body.

This sounds awfully close to the Tai Chi idea of the dantien as a nexus of muscular and tendon power in the body.

As somebody interested in muscle tendon channels and their effect on movement and silk reeling exercises from Tai Chi I can see the correlation here. Tai Chi uses the same principle of movement coming from the centre (the dantien) and that controlling the movement of the extremities through elastic tissue. We usually think of this sort of movement as having to be learned, rather than occurring naturally, however it appears to be exhibited in high-level athletes, as we see in the article linked to above. Are they just naturally doing it? Have they tapped into the way the body is designed to move? Have they stumbled upon it, or have they had to learn to move this way on purpose?

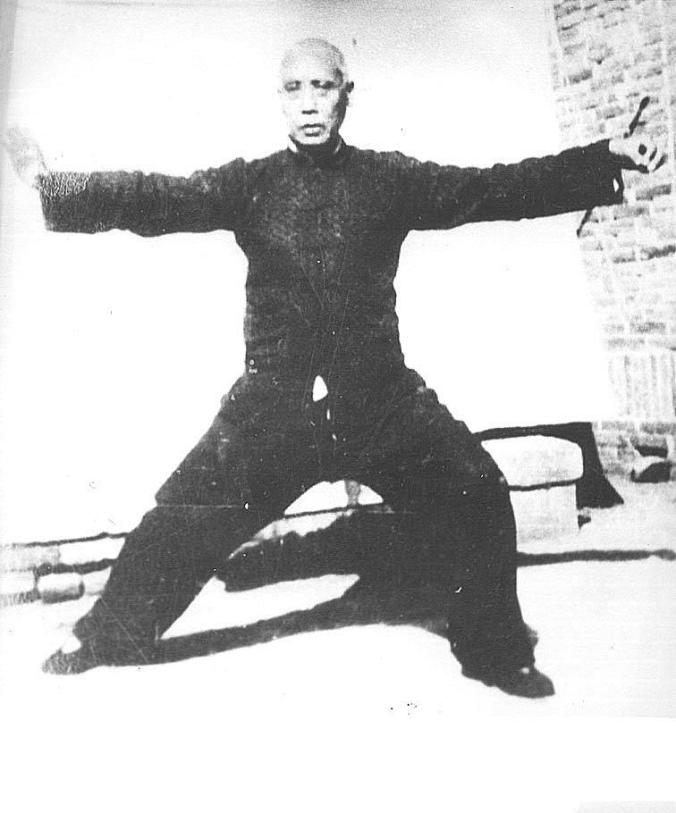

Silk reeling and Shen Jiazhen (1891-1972)

Shen Jiazhen (1891-1972) co-authored the book Chen Shi Taijiquan (1963), which contained the famous silk reeling diagram below:

Silk reeling is the essential skill of Chen style Tai Chi Chuan and involves learning how to wind the body so that all movements arise from the dantien, and that when ‘one part moves, all parts move’. Other styles of Tai Chi do pay lip service to this idea, of course, but I think only the Chen style really gets into it in the level of depth that’s required because they have a deliberate method (Silk reeling) that’s all about this concept.

When I look at family members of other Tai Chi styles perform Tai Chi I don’t see the same type of movement that you find in Chen style. It’s hard to evaluate of course since a lot of Tai Chi masters can hide the details of the movements. I’ve been told that the current head of the Chen style, Chen Xiaowang, is very good at hiding the movement so you don’t see it. But if you look at videos of Wu and Yang family members I don’t believe that the same silk reeling is really going on there. I see lots of really smooth movement (sometimes called “drawing silk”) but not the dantien control that you typically associate with Chen style.

If you understand the concept of silk reeling I see no reason why it can’t be added to these other styles of Tai Chi, of course. In fact, my own lineage started as a Yang style, but it is more of a hybrid style, as it has gone outside of the bounds of a single “family style” and added in elements from elsewhere, including silk reeling from the Chen style. It doesn’t pretend it got it from elsewhere.

When my Tai Chi teacher introduced me to silk reeling he used the pattern in the diagram above from the Shen Jiazhen book on Chen style. Looking back now I realise that this was actually a very difficult place to start with silk reeling because of the pattern’s complexity. It mimics the Tai Chi diagram… but not quite completely. If you look at the bottom of the diagram you’ll see that there’ s an extra little circle going on. The changes from open to close are also really frequent and quick, compared to a standard single arm wave silk reel.

The way my teacher taught me you stood in a forward bow stance and did one arm at a time. Then change stance for the other arm. The illustrations of the hands are pretty accurate and show the way the palm turns nicely. The numbers are important because these indicate the positions where the body changes from open to close and vice versa (with accompanying weight shifts). The diagram on the left is for the left hand and the diagram on the right is for the right hand.

A portion of Shen’s book on the subject of silk reeling has been translated into English and can be read here.

As I said, I don’t think this exercise is good for beginners. A better starting point for learning the basics of silk reeling would be a simple single arm wave. The best instruction I’ve seen on this is by Mr Mike Sigman. In this video (which I’ve posted before, I think) he explains the concept of muscle/tendon channels, open and close and goes over a basic single arm wave and what you should be doing in very clear terms:

A blast from the past – Yongquan demo 2003

This video is a blast from the past (for me, at least). It was filmed in 2003 and I’m in it!

It’s the film of a demonstration the Yongquan Chinese Martial Arts group did in London. There are lots of the arts I was training at the time shown off here – Choy Lee Fut, Northern Shaolin, Tai Chi, Push Hands, then some breaking demonstrations. I’m doing a broadsword form in the demo that I can’t even remember anymore! There’s some Iron palm (a granite pebble broken with a chop) from Donald and a kerb stone gets broken over Doug’s head with a sledge hammer!

Since I was actually in this demo I know that none of these materials are faked – they’re all the genuine article. Real bricks, etc..

At the end of the demonstration there are some clips of us practicing for the demo. These are more enjoyable for me to watch as they bring back some good memories of training with my teacher and the rest of the guys back in the day.

What I like most in the video is the very last clip, where Doug is practising the Press (Ji) technique from Tai Chi on a line of people. Done right it’s meant to be very minimal physical effort with a big results (using Jin not Li) – the power should penetrate through the line of people so that the people at the back of the line fly away first. He does a ‘not very good’ version of it (too much Li – physical force) so it all looks very physical. Donald comes over to tell him off and show him how it should be done, and without any set up does a perfect Ji – really minimal effort and the guy at the end of the line flies off – then Doug has another go and gets it right. I’m glad that got captured on video.