I was interviewed by the great Lou Temlett for the Jiu-Jitsu Lou Podcast recently.

It’s a bit annoying that there is clearly something wrong with my microphone, but it is what it is. (At least the video version below has subtitles!)

I manged to talk about my BJJ book, what tai chi and Chinese martial arts can bring to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu training and some thoughts on different ways of learning and training.

Tai Chi / Taijiquan

Happy Chinese New Year Tai Chi Notebook Family!

Why Tai Chi won’t make you lose weight — according to science

And why you should probably keep doing it anyway

Tai Chi has always felt like it’s very good for me — for the mind, the breath, the joints, for my overall functioning as a human being — but I’ve never really considered it a weight-loss tool. That’s despite the rash of frankly hilarious ads currently clogging up social media, bizarrely presenting Tai Chi as the secret to giving men over 50 a six-pack.

What’s even more galling is that if you actually look at the “Tai Chi” weight-loss exercises these products are trying to sell, they’re not Tai Chi at all. They’re what could most generously be described as basic warm-up movements — and the ripped old men demonstrating them are very obviously AI-generated.

Exercise of any kind is beneficial for health, but Tai Chi has never been particularly associated with weight loss. And now, inconveniently for the entire fitness industry, the idea of exercise as a reliable weight-loss tool has just taken a kick in the teeth courtesy of a recent New Scientist article, which argues that exercise, while very good for you, may not lead to weight loss as much as we’ve been led to believe.

According to the article, the basic problem is compensation. When you exercise more, your body simply burns less energy elsewhere to make up for it — and this effect can be even stronger if you’re also dieting.

As the article puts it:

“Exercise is tremendously beneficial for our health in many ways, but it’s not that effective when it comes to losing weight — and now we have the best evidence yet explaining why this is.

People who start to exercise more burn extra calories. Yet they don’t lose nearly as much weight as would be expected based on the extra calories burned. Now, an analysis of 14 trials in people has revealed that our bodies compensate by burning less energy for other things.” – New Scientist

Seen in that light, it makes far more sense to view Chinese martial arts — Tai Chi included — as tools for improving overall quality of life rather than as weight-loss hacks. That includes balance, coordination, joint health, breathing, mental focus, and, perhaps most importantly, social connection.

Feel the burn

If you’re practicing Tai Chi and want to improve your overall fitness while staying within the Chinese martial arts ecosystem, it’s worth pairing it with something more physically demanding. Styles like Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar, or Praying Mantis, for example, place much greater demands on strength and cardiovascular capacity.

Alternatively, you could lean into the more demanding side of Tai Chi itself — weapons forms, longer routines, or more continuous practice sessions can be surprisingly taxing.

Not all Tai Chi is the same. Most people today practice softer styles, where this advice applies most clearly. Some styles — Chen style in particular — include more vigorous stamping, jumping, and explosive movements, and may not require additional training alongside them.

Either way, common sense still applies. For a well-rounded approach to health, it helps to do something that makes you breathe harder than normal.

Tai Chi doesn’t need to promise abs, calorie burn, or dramatic body transformations to justify its existence. Its value lies elsewhere — in longevity, resilience, awareness, and the quiet accumulation of small benefits over time.

If weight loss happens alongside that, fine. But if it doesn’t, Tai Chi hasn’t failed. It’s simply doing what it has always done best: helping people move better, breathe better, and feel more at home in their bodies — no six-pack required.

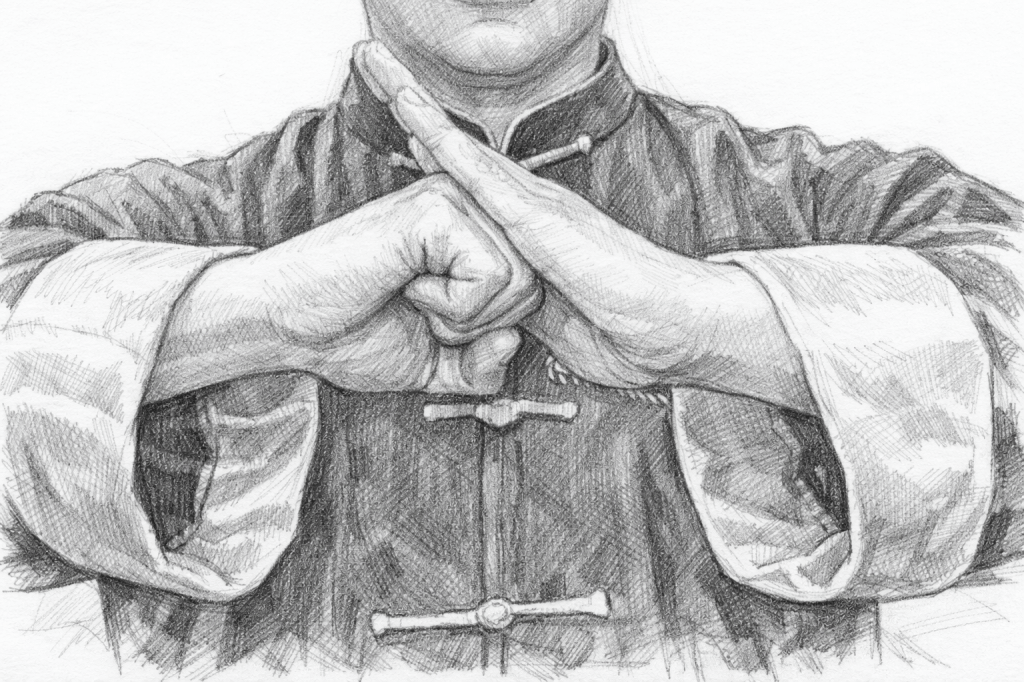

The Tai Chi salute looks polite — its real meaning is much deeper

Behind the gesture is a code about power, respect, and control

I always finish my Tai Chi class, which takes place in the UK and is taught by me, a British person with no connection to Chinese culture outside of martial arts, with a small Chinese-style salute.

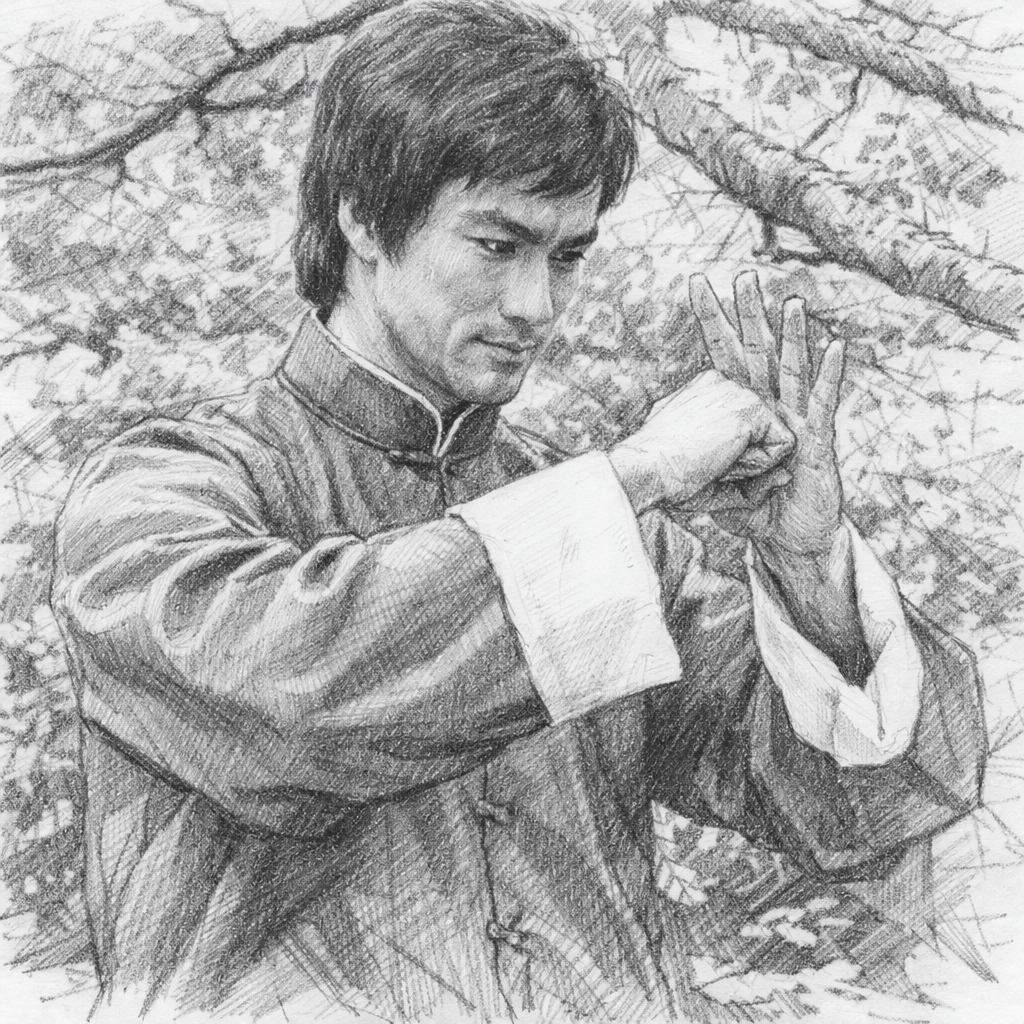

Often called the “sun and moon” salute, it’s a traditional greeting in Chinese martial arts circles. It’s the same one you see Bruce Lee do to his student at the start of Enter the Dragon. But like most things in Chinese martial arts, it has both an obvious meaning and a hidden one. Of course, you don’t need to know the hidden meaning to use it.

In Chinese, the salute is called bàoquán lǐ, which roughly translates as “fist-wrapping rite.” Your right hand forms a fist — the “sun” — and your left hand presses flat against it — the “moon.” You stand straight, feet together. It’s accompanied by a short, respectful nod of the head rather than a deep formal bow, while maintaining eye contact.

Sometimes the fingers are folded instead. This seems to be a softer, less formal greeting (and it’s the one I usually use). This variation is often called gōngshǒu lǐ (“cupped hands greeting”) and is traditionally gendered — the closed fist is the right fist for men and the left fist for women.

It’s worth noting that this is far from the only hand position used for greeting across China’s long history, particularly within religious traditions.

Why do it?

The bàoquán lǐ isn’t a tradition added to Chinese martial arts — it’s a remnant of a moral code that existed before they were formally named.

At a basic level, the fist represents martial skill or strength, while the palm represents civility, restraint, and wisdom. The palm covering the fist symbolizes martial power governed by virtue or, put simply: I can fight, but I choose respect and control.

When I do it at the end of class, it’s quick and almost reflexive, sometimes even a little embarrassed. I don’t expect my students to do it back. It’s a brief gesture with a clear purpose: it marks the end of the session and acts as a quiet “thank you” for the work they’ve just done.

When I do it to my kung fu teacher, it carries a different weight. My teacher (who is not Chinese) still greets his own teacher (who was Chinese) with this salute every time they meet, and that tradition was passed on to me. I still greet my teacher this way whenever I see him. Even though it isn’t part of my culture, the meaning is clear when I do it.

In that sense, I suppose I’ve passed on a “light” version of the tradition to my own students by using the salute at the end of class. Even if they don’t return it, it’s something they now recognize. The tradition has softened over time, we don’t use it to greet each other, and honestly, I think it would feel strange if we did.

I’d describe my teacher’s period of training with his teacher as serious, and my own training as semi-serious by comparison. People in modern Tai Chi classes aren’t devoting their lives to this with the all-or-nothing commitment that might have been expected in 1860s China. For most people, it’s a hobby. A social activity. Ideally, people leave class feeling better than when they arrived, or at least like they’ve worked hard and learned something.

Hidden meanings

As with most things in a culture that has existed continuously for thousands of years, meanings tend to come in layers.

The sun and moon are obvious representations of yin and yang, shown here as equal forces held in harmony, suggesting balance rather than dominance.

There’s also a practical dimension. A level of formality in martial arts is useful. What we’re engaging in is potentially dangerous, and maintaining respectful ritual helps reinforce that fact.

(Incidentally, that’s one reason I don’t mind bowing in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu training too. We routinely put our training partners in potentially life-changing situations, and a moment of ritual respect is a good reminder that what we’re doing carries real consequences.)

One of my favorite hidden interpretations, though, comes from Chinese history, specifically the Ming–Qing dynasty transition.

The Ming were the last ethnically Han Chinese ruling dynasty. The Qing were Manchu invaders from the north, and they were deeply unpopular with large parts of the population. Resistance movements emerged almost immediately.

The slogan “Overthrow the Qing, restore the Ming” (反清復明, Fǎn Qīng fù Míng) became a rallying cry for secret societies and rebel groups from the fall of the Ming in 1644 well into the early 20th century.

The bàoquán lǐ salute was reportedly adopted by some of these movements as a covert signal of allegiance. The closed fist was said to represent the character for sun (日), while the open palm represented moon (月). Together, these two characters form 明 (Míng), meaning “bright” or “to illuminate,” and also the name of the fallen dynasty.

Which means that, technically speaking, every time I’ve used this greeting, I’ve been quietly expressing support for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

But no, my Tai Chi class isn’t secretly plotting the restoration of a long-collapsed Chinese dynasty. But I do like the idea that a small, slightly awkward gesture at the end of a community hall class carries echoes of philosophy, rebellion, and restraint. Even if most of the time, it’s really just a polite way of saying: thanks for showing up — see you next week.

In Tai Chi you don’t look down — or do you?

Learning how to extend the qi

When I’m teaching my Friday class one of the things I quite often say is “don’t look down” – however, like most of the short, pithy statements you hear delivered by Tai Chi teachers… it’s not really true. Rather, it depends on the context of what you’re doing. Let me explain.

Yes, generally speaking, you want to be looking at the horizon when doing Tai Chi because you want to keep your head and neck aligned with your spine. Specifically with the head and neck we are talking about the posture principle of ‘suspending the head’. However, there are times in Tai Chi, where it is perfectly acceptable to look down – particularly on moves where the direction of the application is down towards to the ground.

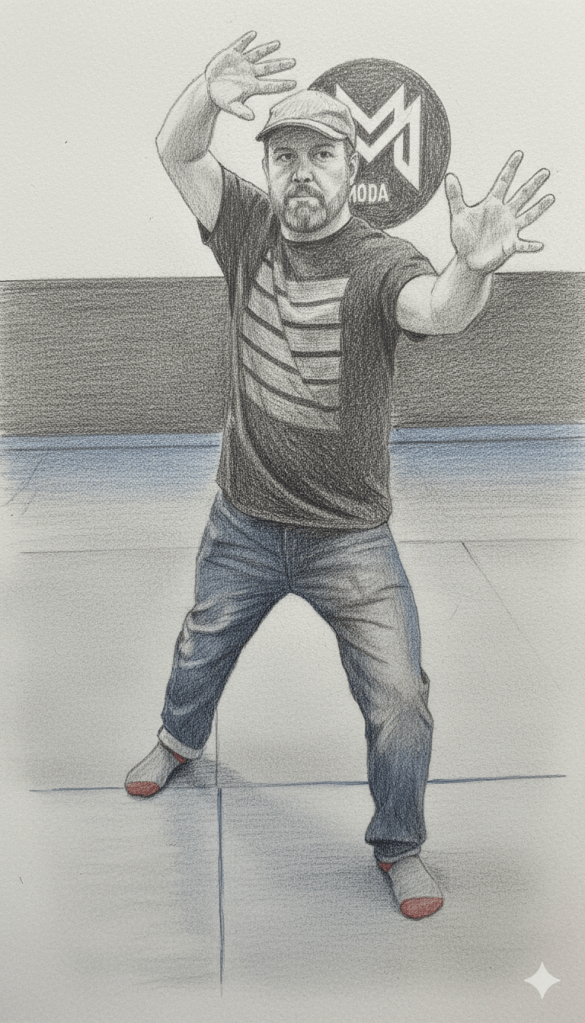

Like our White Crane Cools Wings, for example:

White Crane Spreads Wings from the ‘short short form’ I teach.

The reason I say “don’t look down” a lot when teaching is that people learning a Tai Chi form have a general tendency to look down (me included!). Generally as we age our posture seems to become more slumped forward, perhaps because we sit down a lot in modern life, but also because scanning the horizon for signs of danger has long since stopped being an evolutionary priority. We also use computers, phones and devices all the time, and they lead to a general posture of our heads being tilted forward slightly. This can result in people doing the whole Tai Chi form while never looking up from the ground.

Extending the qi

In Tai Chi you want to have a feeling of a slight stretch all over the exterior of the body at all times – that’s really what following the posture principles of Tai Chi gives you – things like flattening the lower back, rounding the shoulders and suspending the head. This is known as ‘extending the qi’ all over the body. When you stand in a Zhan Zhuang posture you can feel this slight stretch all over the surface of the body that the posture generates – it’s subtle, but that’s what you’re looking for.

Suspending the head is part of that extension of the qi over the head, and you can keep that extended feeling even when you glance down. What you definitely don’t want to do is break the alignment of the spine and neck, which is what typically people do when looking at their phone, or their feet:

Looking down at your phone. Photo by Thom Holmes onUnsplash

If you want a good fix for this then I find regular Zhang Zhuang (“post standing” or “standing like a tree”) practice is a good way to remedy this and retrain your head position on a subconscious level. Master Lam has a 10-day course on the subject.

The problem with looking down is that our head is rather heavy (between 2.3 and 5kg), and when you take your neck out of alignment with your spine your body automatically compensates for the extra weight that is pulling it forward (or you’d fall) and it does that by tensing some of its posture control muscles, particularly in the middle of the body, and that can interfere with the relaxation and freedom of movement we are looking for in Tai Chi. You also aren’t creating an optimal path for sending incoming forces to the ground or for sending jin up to the head. You are also not ‘extending qi’ to the head.

If you’re going to look down then you need to do it while keeping that slight stretch up the back of the neck and over the head.

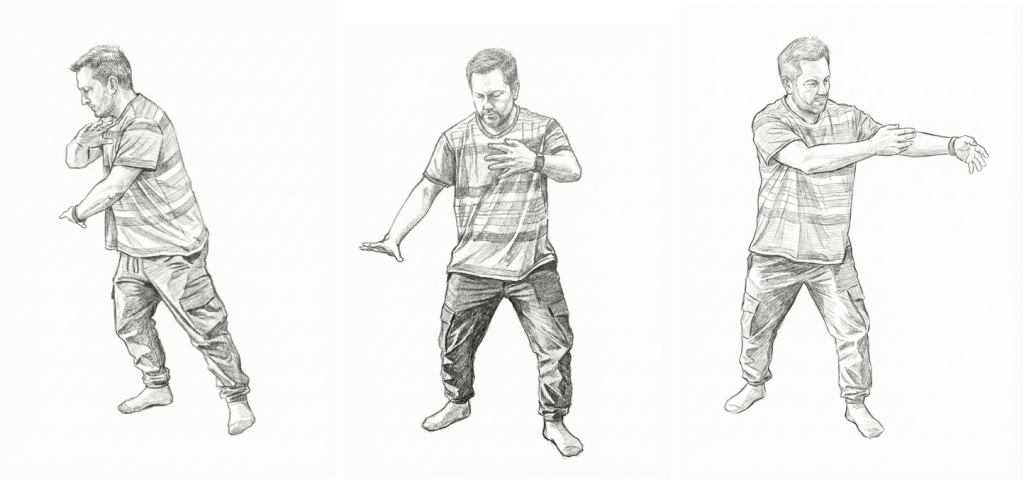

Ward-off and martial applications

‘Ward off’ is another example of a posture where I do look down, although it’s only briefly. I look down because of the martial application I’m thinking of. My active hand in that posture is first the back hand, which I’m using to send my imaginary opponent to the floor. The front hand can then be used as a deflector, so after I’ve dispatched the first opponent to the floor, I then look up and deflect the second attack, which leads into the ‘roll back’ posture.

Here is the sequence:

In this sequence, the ‘ward off’ is the middle picture, and my focus is on my right hand pushing down from where it was in the previous picture, then in the next picture I refocus on the left hand deflecting, and getting ready to perform a ‘roll back’.

Here’s a much younger and hoplessly naive version of myself showing the marital application at around 19 seconds in this video:

As you can see, where you are looking in the Tai Chi form is dependent on what application you have in mind when doing the movement. So, while there are some useful maxims to remember in Tai Chi, such as ‘don’t look down’, it’s important that you know when it’s acceptable to bend the rules so that your Tai Chi becomes a living practice, with things done for a reason, not just blindly following the rules.

Episode 41: Teaching Tai Chi as a Martial Art with Nick Walser and Ian Kendall

In this episode I talk to two Wudang Tai Chi teachers from Brighton, UK: Nick Walser and Ian Kendall. Both students of the late Dan Docherty, they have continued to practice the tai chi that Dan taught them and developed a new training system called 5 Snake.

5 Snake is a unique and powerful method for finding flow, resilience, and calm through partnered close- quarter practice, and they’re here to tell you all about it.

Find out more at 5 Snake and on Instagram, YouTube and Facebook.

Tai chi and keeping the spine aligned with the head

“An intangible and lively energy lifts the crown of the head.”

One of the things I often notice about my rolling partners in BJJ is that when they’re passing guard, they’re too easy to pick apart and attack because they let their spine bend by allowing their head to drop. As soon as this happens, I can attack their limbs easily because they’re suddenly not as strong. The spine is an integral part of the structure of our body, and when it’s not properly aligned, we’re weaker.

When we’re rolling in BJJ, and I’m in teacher mode, I’ll stop and point out when their head is down, and it’s often a kind of revelation to them. What I mean by “when their head is down” is that their head (and neck) is not in alignment with the rest of their spine. Once your head is aligned with your spine, you’re much stronger physically, without even trying. You’re also much more resistant to attacks from your partner. The game in BJJ then becomes about how you can break their spinal alignment while they try to keep theirs and break yours.

This takes you beyond the realm of just techniques and into the realm of principles. My BJJ book is certainly full of techniques, but I also tried to include a lot of text, especially in the intro pages for each section, about principles and strategy, too.

Having a background in tai chi, I think I’m more aware of spinal position than people who don’t have some sort of bodywork background before they start BJJ. In the 10 essentials by Yang Cheng-Fu as recorded by Chen Wei-Ming, it says, “An intangible and lively energy lifts the crown of the head. This refers to holding the head in vertical alignment in relationship to the body, with the spirit threaded to the top of the head. One must not use strength: using strength will stiffen the neck and inhibit the flow of qi and blood. One must have the conscious intent (yi) of an intangible, lively, and natural phenomenon. If not, then the vital energy (jingshen) will not be able to rise.”

Now there’s a lot of Chinese jargon in there that we can probably do without, and the way it’s written is not incredibly helpful. In BJJ, I usually just say “keep your head up” because that covers a multitude of sins, but what I’m really talking about is keeping your head in alignment with your spine.

If I’m teaching tai chi and I tell a student to keep their spine “vertical,” or lift “the crown of the head,” as it says in Yang Cheng-Fu’s recorded sayings, they almost immediately stiffen up straight like a soldier, holding their shoulders rigid and looking really uncomfortable. That’s not what you want in tai chi.

I think this stiffness is what Yang Cheng-Fu meant when he said in the next sentence of Chen Wei-Ming’s work: “One must not use strength: using strength will stiffen the neck and inhibit the flow of qi and blood.” A good tai chi spine is not a fixed position; it’s an alignment, and that means it’s an ever-changing position that adapts to your movement.

The general movement of your body in tai chi is always down. You are always relaxing and sinking down. That doesn’t mean you give up and slump on the floor like jelly; it means you just stop trying to hold yourself up all the time. You don’t really ‘do’ anything.

Relax the shoulders and just stand still for a bit in a wu chi posture. If you relax and allow it to happen, your head will naturally find the right spot where it sits in balance on top of your spine. The key is to stop trying to make it happen and let it happen. It wants to be there; you’ve just got to get yourself out of the way and allow it to happen. As it says in chapter 2 of the Tao Te Ching, “The sage acts by doing nothing.”

You’ll know when it feels right, and you can transfer that feeling to other situations: driving, working on a computer, and even, doing Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

1980s Wushu, China (Bagua, Tai Chi, Northern Shaolin)

Just watched a great clip of 1980s Wushu in China – featuring Sun Jianyun, Sun Lu Tang’s daughter performing Bagua. But there’s also some clips of Tai Chi and some kids doing Northern Shaolin (at least I think it’s Northern Shaolin). Well worth a watch. The martial arts are on their way to being the heavily performance-based WuShu we have today, but are not quite there yet, with martial technique still a priority.

Real men do Tai Chi, apparently

The latest way of selling tai chi is to say it gets you jacked

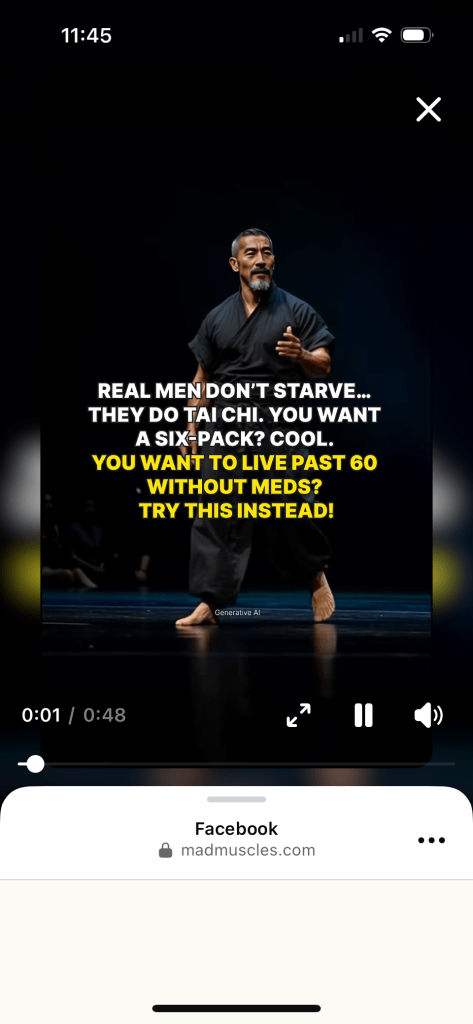

I’ve seen a lot of things come and go in the Tai Chi universe over the years, but the latest marketing trend has got me scratching my head. Almost every advert for Tai Chi courses I see on Instagram and Facebook at the moment promises ripped muscles and a hyper-masculine physique, mainly for men over 50!

Tai Chi, with its soft, slow, flowing, gentle movements, is perhaps the least masculine-looking martial art you could imagine, yet here is “Master Lee” strolling around a TV studio with his top off showing off his impressively-muscled abs, which he says he got from tai chi.

Or this guy, who claims tai chi is the path to a six pack. “Real men don’t starve… they do tai chi”, he proclaims.

So, what’s going on here?

Firstly, these confident, super-tonned Chinese gentlemen, are clearly creations of generative AI video apps. Everything about the videos looks as fake to me as the idea that tai chi on its own will get you that shredded.

Tai chi is good for many things, like learning how to use qi and jin and producing a feeling of tranquility, or as a self-defence system, but producing athletic-looking people over the age of 50 is really not one of them. *

When you look deeper into the exercises being offered here they look like simple, repetitive qigong-style movements. The idea that you’d replace weight training and body weight exercise with these and still build muscle is wrong, as far as I can see.

There’s no getting away from it, if you want to lose weight and build muscle you need a diet, cardio and weight training routine.

—-

* Now, I’m aware that there is another trend at the moment to train intensively with kettle bells and call that “tai chi” or “internal”, but really it’s no different to doing a kettle bell workout and not calling it tai chi.

Wudang mountain’s martial arts tourism empire

This is an excellent article called The Sacred Cash Cow: Wudang Mountain’s Martial Arts Tourism Empire by The_Neidan_Master on the massive amount of commercialisation of the martial arts in Wudang, which has really leaned into its claims as the birthplace of tai chi.

I don’t think it’s worth debating the authenticity of these claims again, I’ve done a couple of podcasts with people who have lived at Wudang and trained there, one with Simon Cox, and the other with George Thompson – both very different experiences, which reflects the diversity over such a wide area, since Wudang is a vast collection of mountains and temples/schools, rather than a single place – and I don’t know what more is gained by going over that ground, but I think it’s better to simply accept that there is a growing cultural force that is pushing Wudang, a traditional home of Taoist studies, as one of the centers of modern tai chi training.

If your goal is to train tai chi at Wudang then its worth reading the article to get a balanced view of the place before going there.

Here’s a great quote:

“For travelers seeking authentic martial arts experiences at Wudang, awareness of these commercial realities provides crucial context. Understanding that most schools are modern businesses rather than ancient temples allows for more informed decisions about where and how to invest time and money.”

I think we have to accept that for ancient traditions to exist and continue in the modern age there needs to be some soft of commercial aspect, but that means that you need to approach these traditions with eyes wide open.