We’ve confused the professional version of jiu-jitsu with the version most people actually practice

Every year, a BJJ celeb sounds off about how the gi* is dying and no-gi is the future. And yet, the death of the gi never actually happens — and I don’t think it ever will.

While the pro scene screams “no-gi future,” the average BJJ practitioner is still tying their belt every night. Here’s why.

If you only watch professional BJJ, you’d be forgiven for thinking the gi is already dead. But it’s a mistake to confuse what we watch with what we actually do.

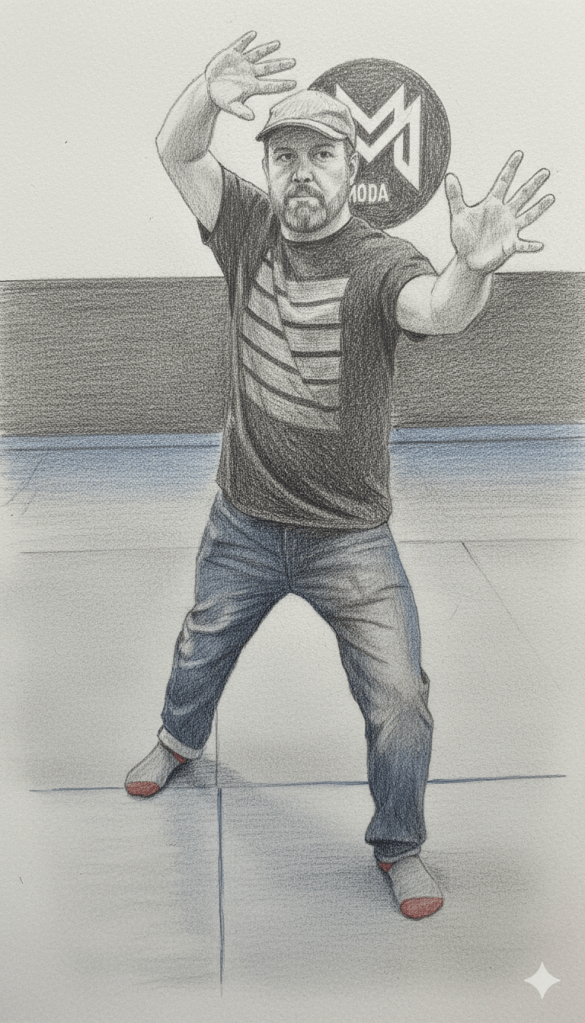

Take my own academy as an example: we run roughly twice as many gi classes as no-gi. That’s driven by demand, not coach preference. Not every gym is the same, but I don’t think this is unusual — at least not in the UK.

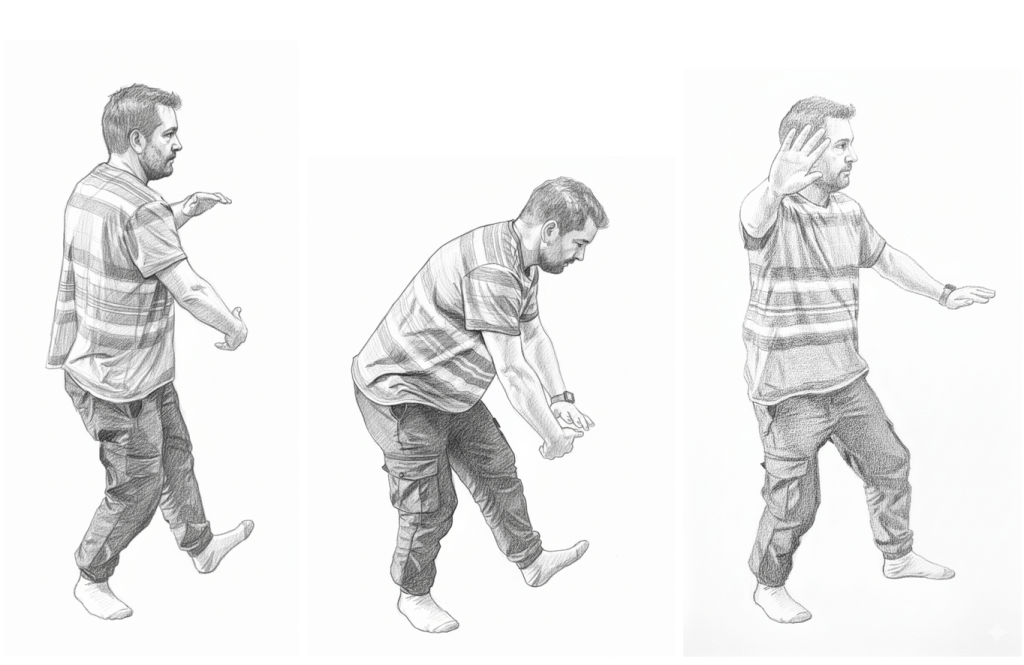

Last year I went to Camp Eryri, a BJJ training weekend in North Wales. There were workshops in both gi and no-gi, but when it came to open rolling, most people chose to train in the gi. The majority of workshops leaned that way too.

Sure, no-gi dominates pro events, streaming, and social media clips. But the gi still dominates hobbyist practice, traditional gyms, and the belt progression culture that keeps people coming back. So why is that?

Why no-gi looks like the future

You often hear that the gi is boring to watch, but I don’t think that holds up. When a gi match appears on a Polaris card, it’s often one of the most engaging fights of the night.

And no-gi isn’t immune to the same problems. Matches can devolve into long stretches of unproductive stand-up, followed by a last-minute scramble or leg lock exchange that feels more like a coin flip than a conclusion.

Let’s be honest: no-gi dominates the pro scene partly because it looks better—more athletic, more modern, more like MMA. Tight rashguards, visible physiques, more tattoos, faster scrambles—it’s easier to sell and easier to package.

With fewer grips, it’s also theoretically easier for casual viewers to understand. There are also supposed to be fewer opportunities to stall—again, in theory. In practice, anyone who’s watched recent ADCC trials knows that stalling is alive and well in no-gi too.

No-gi also benefits from crossover appeal. Wrestlers and MMA fighters can step in more easily, and if BJJ ever pushes for Olympic recognition, the argument tends to favor no-gi.

But the gi isn’t going anywhere.

Belts still matter in BJJ, and people value the sense of progression that comes with them. It’s addictive. It gives structure. It connects you to the history of the art.

Then there’s the technical depth. The gi adds layers—grips, controls, positions—that appeal to the more analytical side of training.

And perhaps most importantly, the gi is still the default language of BJJ worldwide.

I understand why some people prefer no-gi. The gi can be tough on your fingers. It can be frustrating when someone neutralizes your athleticism using your own clothing. And yes, there’s a lot of laundry.

But I don’t mind the laundry. I like having a few clean layers between me and my opponent. It feels more hygienic, and less like I’m stepping into a low-level germ warfare experiment every time I train.

In competition, both styles can be boring. The real issue isn’t the uniform — it’s the rule set.

No-gi will probably continue to dominate the professional scene. The gi will continue to dominate everyday training. And that’s fine.

We haven’t stopped training in the gi—we’ve just stopped paying attention to it.

(* If you’re new to BJJ: the gi is the traditional uniform, similar to judo, while no-gi typically involves a rash guard and shorts.)