I don’t feel I’ve written enough about body mechanics recently. I’ve been too busy enjoying myself reviewing books and interviewing people for podcasts, but I guess it’s time I stopped having fun and got back to being serious!

Watching a video of Professor Cheng Man Ching for my recent book review of Yang Short Form, I was struck by how little the Professor used his arms in his Tai Chi form. Take a look:

Sometimes it looks almost like he just gives up as his arms go limp! (Like at 1.20 in the video). This is one of the big criticisms I hear of the Cheng Man Ching form – that it’s a bit limp – but if you look at what his legs are doing it’s a bit like watching a swan on the water – you can’t see anything moving above the water, but beneath it there is a lot going on.

There are plenty of people in the Tai Chi world who disparage Professor Cheng Man Ching and his abilities. They claim that it was really his high level political connections in the exiled Nationalist government in Taiwan that made people praise his Tai Chi, not his actual abilities in the art. However, I think his impact on the Tai Chi world has been undeniably huge, and he attracted a lot of students, many of whom came from other martial arts and were experienced in those arts. I don’t think that would have been possible without some real ability being offered. From watching videos of his form and push hands, his deep rooting in his legs and ability to transfer the ground force into his opponents looks impressive to me. While there is no evidence of him transferring this ability into an actual martial art, he did appear to actually engage people in playful push hands on a regular basis, something a lot of Tai Chi teachers don’t do.

Cheng Man Ching was heard to say that he once had a dream where he had no arms and it was only after that that he felt he understood Tai Chi. That’s what his method looks like to me – the arms don’t matter. He’s sunk very low in his legs all the time, channeling the ground force upwards into his torso, and the arms are almost an afterthought, held up with as little energy as possible.

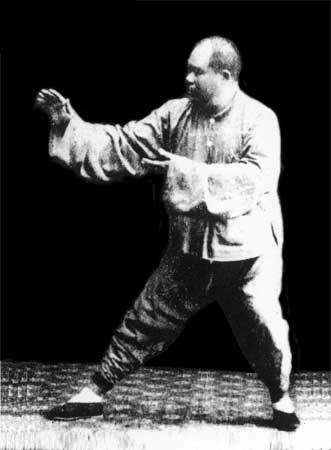

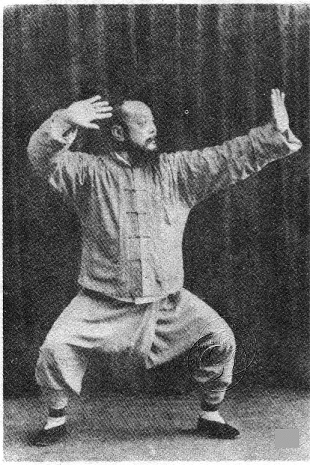

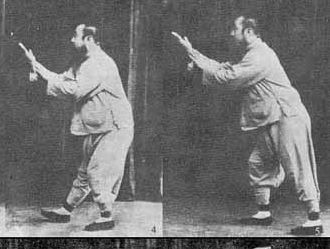

Personally, I can’t say I’m a fan of this method. To me it seems logical that in Tai Chi your body needs to have the sense of being stretched slightly from fingertips to toes at all times. I don’t mean stretched in a Yoga-like way, I mean that the skin needs to feel stretched over the bones and muscles, as if you’re made of rubber. Take a look at a picture from history of Wu Chien Chuan, of Wu style or Yang Cheng Fu of Yang style and I think you can see what I mean.

That way it’s like a guitar string being tightened so that it makes a sound when plucked in the middle. A lax string can’t be played. In Tai Chi that ‘middle’ is your dantien. If you’ve got a slight stretch on your body, from fingers to toes, then you can control movement along the length of this stretch using your dantien, so a movement of the dantien will naturally affect a movement of the extremities, if you let it.

The classics use the analogy of a bow, the most famous line being “Store up the jin like drawing a bow.”

Anybody can feel this stretch by adopting a Tai Chi posture and relaxing and trying to create an expansive feeling, but it gets stronger over time and with repeated practice. A lot of the chi kung exercises that come along with Tai Chi are designed to help you feel this stretch from fingers to toes, and help to make the connection stronger and more usable over time.

Chen Man Ching’s idea of Tai Chi seems different to me. It’s more like he’s got no arms and the jin is stopping in his shoulders, not reaching his hands. At least that’s how it appears to me.

A very good way to gain insight into Professor Cheng’s method is to read Wolfe Lowenthal’s three books on his studies with Professor. I believe Professor Cheng’s form embodies the principles of philosophical Taoism. There are, too, quite a few reports of his martial ability. And he impressed a number of martial artists in New York who became his students.

LikeLike

my own sifu (in the yang style lineage) had a similar loose appearance in structure when demonstrating but was very focussed on promoting core stability with precision in alignment & positioning when teaching .. i think at 80 when that sequence was filmed, the professor didn’t need to impress anyone or prove anything anymore !! he knew his abilities .. anyone i’ve ever read of who had the fortune to interact with him has expressed the same sense of him reflected in these comments. to me, his form in his older years reflected a sense of grounded repose. cheng was beyond needing to practice being empty externally, he simply was. his distracted air & limp movements are a deceptive invitation to underestimate his power. like the samurai in the book of 5 rings he would be able to respond before an opponent had even decided on a move

LikeLike

I understand what you’re seeing/saying, but I think of it a little differently. The videos we have of the professor are from when he was a little older. He had a fairly short and frail build, combined with his age, and this effected how it was expressed externally. I think you are correct in that this partly his conscious decision, but it’s also his own unique expression due to his build. He was a painter and calligrapher, the expression through his arms and hands are kind of like, abstract artistic brush strokes rather than clear, literal depictions. It’s implied, not spelled out as someone else suggested.

I also find it interesting that when you watch his students, or those several generations later from the Professor’s ‘branch’, they retain some of this expression. It’s kind of touching, like a tribute. Something done out of reverence. The really good practitioners, like my teacher, have the Professor’s ‘flavour’, but you can also see their own unique expression. My teacher has a rather stocky build, and his form retains the professors softness but with a stout, stocky sort of twist. It should reflect the truth of who you are, not try to conform exactly to the shape of someone else, who also had a unique body.

On a slightly different subject, but I’ve often wondered what it would look like if an amputee were to practice the art. Perhaps they were amputated at the elbow or shoulder on one arm, or both, or perhaps the legs. Would they not be able to do it ‘correctly’? That’s sort of an extension of the Professor’s dream about having no arms.

it seems that what is going on inside is more important than how it appears externally, at least to me.

LikeLike

Kia ora, tatou katoa, my name is Mike Baker and I live in Gisborne Turanganui a kiwa, NZ Aotearoa. I have been practicing Grandmaster Ch`eng Man-Ch`ing`s 37 posture Short Form for 49 years and teaching it for 39 years. I am English and began my journey with my first teacher in England before emigrating to NZ Aotearoa. While I have endeavoured to preserve and demonstrate my understanding of the Professor`s principles and those of the wider world of Taijiquan, my focus through this time has been on a practical application of the postures within the Form, for self-defence, as well as practice for the enhancement of health and well-being. So I train in single and double hand, fixed step and moving Push Hands, Ta Lu and San Shou or San Sau and free form; Staff, Cane, Dao and Jian sword forms and Steel Fan. As I was never privileged to train with the Professor my own perception and practice of his Short Form has inevitably been limited, as I place great store on learning through a ‘hands-on’ practice. I believe that there is no substitute for actual, physical connection within the pedagogy associated with this kind of intimate learning.

In response to this post my own perception of the Professor`s Form practice is that, as he himself stated, his Solo Form evolved and changed over the years from a more practical, martial practice to one that was governed by the desire for more Song Gong – the release of tension. Certainly so much of his commentary over the years was extolling the virtues of relaxation. So when I watch the videos of him in his later years it comes as no surprise to me that his arms appear soft and yielding, while still demonstrating the actual postures and to me, I do not read this is as ‘limp’. There is still definition and integral connection with the rest of his body. How could there not be? As I have physically connected with other Taijiquan Masters in the past, I know that the appearance of ‘softness’ in their movements can be very misleading and surely, Taijiquan is supposed to be like this. This is the Way. We know from the Classics that there is an almost paradoxical dynamic in the way that the lower body provides the firm grounding and source for energetic projection through the more mobile, released upper body and arms. Paradoxical, yet not so, for the whole body moves as one – merely another expression of yin and yang functioning inseparably. So I do not see ‘limp’ at all in Ch`eng Man-Ch`ing`s arms. I see that ultimate expression of softness which still remains intrinsically connected to the rest of his body and while the arms do not ‘spell out’ the movements externally, the integrity of execution and intention is still right there and perhaps more so than if the movements were clearly recognisable as functioning for self-defence: Yi, the mind leads all. Just because there is subtlety evidenced does not mean that there is nothing going on . As I turn 70 this July and my own practice gradually changes, the demonstrations of Grandmaster Ch`eng Man-Ch`ing remain, for me, the height of complete and whole Taijiquan practice and definitely something to aspire to.

Thank you, Ngā mihi nui,

Mike Baker

LikeLike

When I studied Professor Cheng’s form in the early ’80’s, my teacher (whose own teacher had studied with Master Cheng) taught us “fair maidens hands” to keep the flow of chi moving through body and arms and hands without being cut off suddenly at a limp wrist.

LikeLike

II had the privilege of studying with the Ch’an Master Liu Piu in London in 1970’s and can echo Susy Sunshine’s experience of being in the presence of a Master. You feel it and you never forget it.

LikeLike

Was Professor Cheng just following the Tai Chi Classics?

From Wu Yu-hsiang’s Understanding the Skills Developed by Practice of the 13 Postures: “First seek the open and expanded, then seek the compact and gathered. In this way, you will make meticulous progress!”

From Chen Weiming’s commentary: “In practicing both form and push hands, you must first seek open and expanded. (…) Once you have gongfu skill, then seek the compact and gathered. From big circles arrive at small circles. From small circles arrive at no-circle.”

(Translations are from Lee Fife: https://www.rockymountaintaichi.com/translations)

LikeLike

I’m a student of Chen Man Ching’s 37 movement form, and there is an interesting anecdote in his book “Master Cheng’s new method of Taichi Ch’uan self-cultivation” where he mentions struggling to improve his technique when studying with yang Ch’eng-fu. He says that he “dreamt that both my arms were severed from my body. The next morning I applied this sensation to my taichi and achieved a new level of relaxation. My sinews and vessels felt connected to my arms with no more strength than rubber bands connect a baby dolls arms – they could manoeuvre freely and unobstructed.”, so perhaps it’s a defining feature of his style of taichi?

LikeLike

I had the privilege of studying with Professor Cheng in the early 1970’s. All one had to do was walk in the room and feel the chi centered in as well as emanating from the Professor. If you were lucky enough to have direct physical interaction with him, and were open to the experience, he generously extended his chi into your being. The gift of having been in his presence has permeated my life. I only hope I have passed what he embuded in me forward as much as possible.

LikeLike

As a longtime practitioner of professor Cheng’s tai chi, and having only ever had the opportunity to study his form, I’ve wondered the same thing. Thanks for bringing this up.

I have never been able to bring myself to let the chi drain out of my arms, back and chest in order to effect that limp state. Fortunately his book Cheng Tzu’s Thirteen Treatises on T’ai Chi Ch’uan contains photos from when he was younger that appear to show a much more charged expression of the form, demonstrating a balance between the expression on the legs and the rest of the body. That book has always been my model, and as a matter of fact my teacher who studied with professor Cheng, Maggie Newman and Ben Lo, didn’t teach the form with the droopy arms.

LikeLike

That was a very interesting video. I have never bothered to study that branch anything at all. Very special! Limp indeed! I can totally see what you mean, as it’s solid up until a point and then it just, stop. Odd!

LikeLike