I don’t feel I’ve written enough about body mechanics recently. I’ve been too busy enjoying myself reviewing books and interviewing people for podcasts, but I guess it’s time I stopped having fun and got back to being serious!

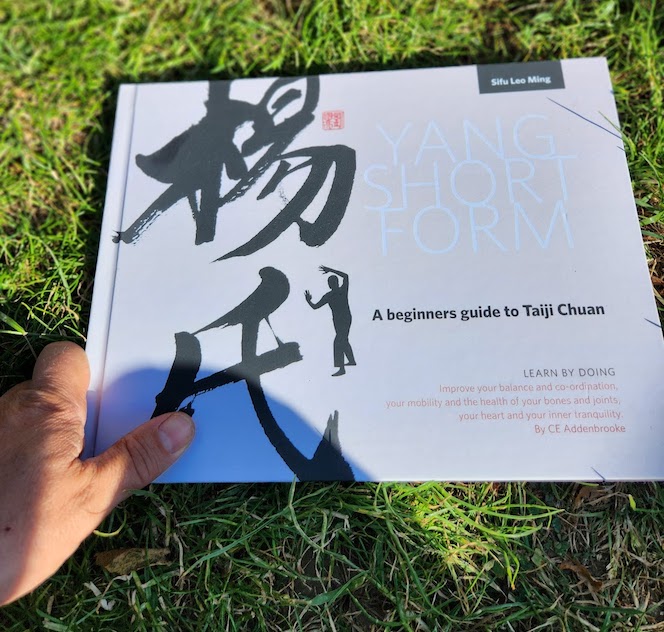

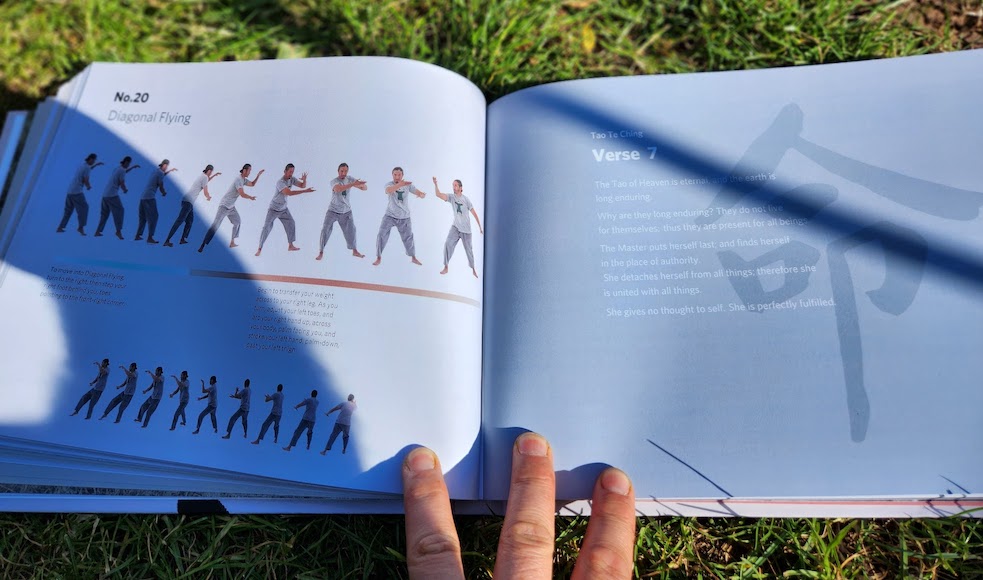

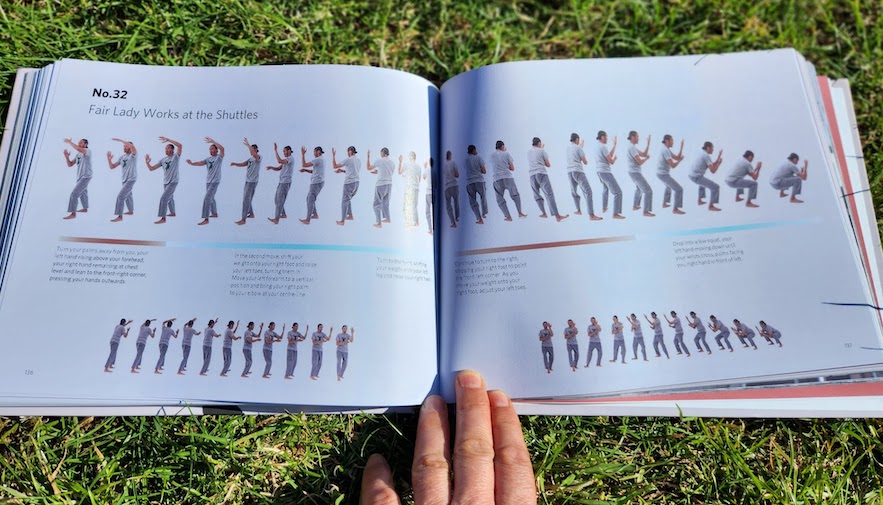

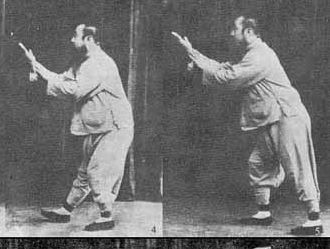

Watching a video of Professor Cheng Man Ching for my recent book review of Yang Short Form, I was struck by how little the Professor used his arms in his Tai Chi form. Take a look:

Sometimes it looks almost like he just gives up as his arms go limp! (Like at 1.20 in the video). This is one of the big criticisms I hear of the Cheng Man Ching form – that it’s a bit limp – but if you look at what his legs are doing it’s a bit like watching a swan on the water – you can’t see anything moving above the water, but beneath it there is a lot going on.

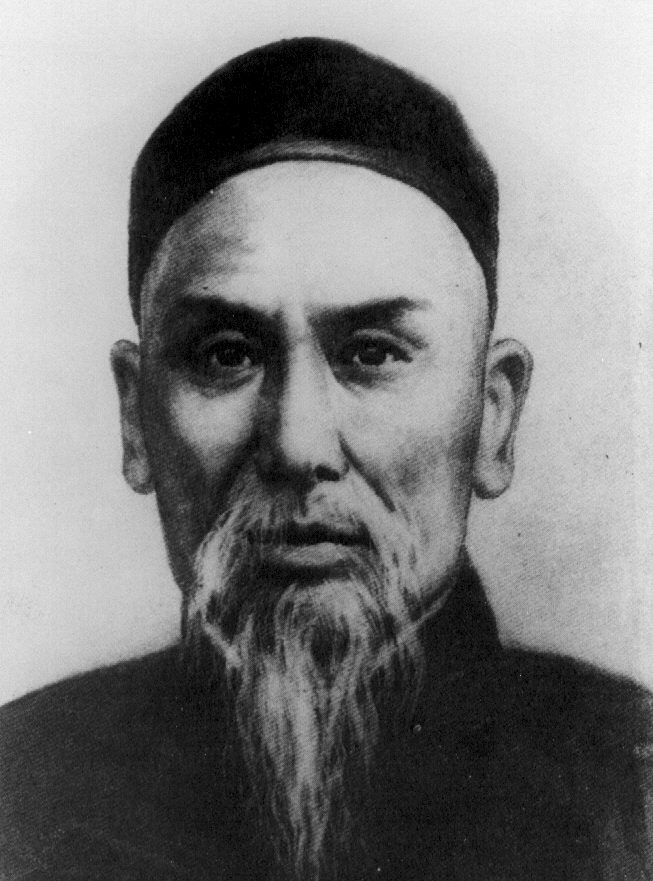

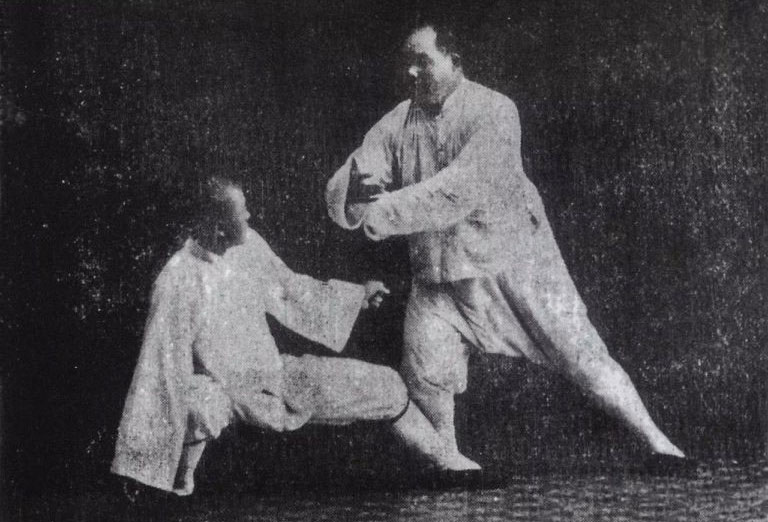

There are plenty of people in the Tai Chi world who disparage Professor Cheng Man Ching and his abilities. They claim that it was really his high level political connections in the exiled Nationalist government in Taiwan that made people praise his Tai Chi, not his actual abilities in the art. However, I think his impact on the Tai Chi world has been undeniably huge, and he attracted a lot of students, many of whom came from other martial arts and were experienced in those arts. I don’t think that would have been possible without some real ability being offered. From watching videos of his form and push hands, his deep rooting in his legs and ability to transfer the ground force into his opponents looks impressive to me. While there is no evidence of him transferring this ability into an actual martial art, he did appear to actually engage people in playful push hands on a regular basis, something a lot of Tai Chi teachers don’t do.

Cheng Man Ching was heard to say that he once had a dream where he had no arms and it was only after that that he felt he understood Tai Chi. That’s what his method looks like to me – the arms don’t matter. He’s sunk very low in his legs all the time, channeling the ground force upwards into his torso, and the arms are almost an afterthought, held up with as little energy as possible.

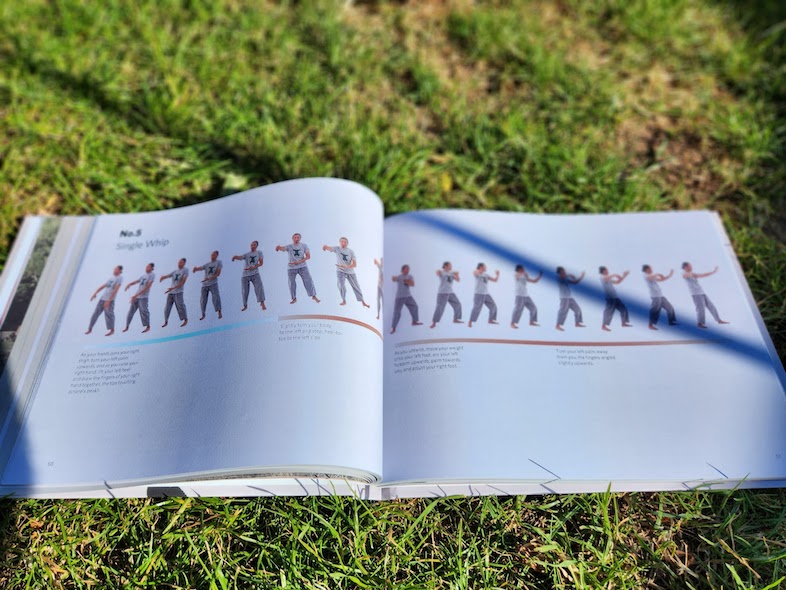

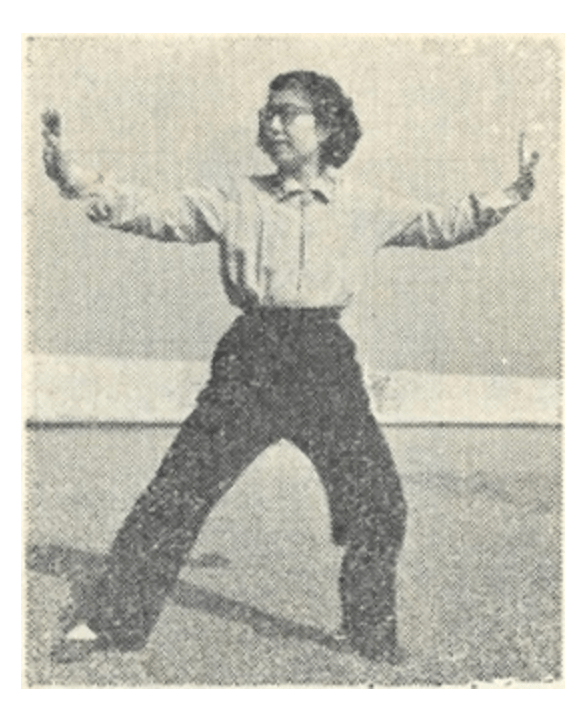

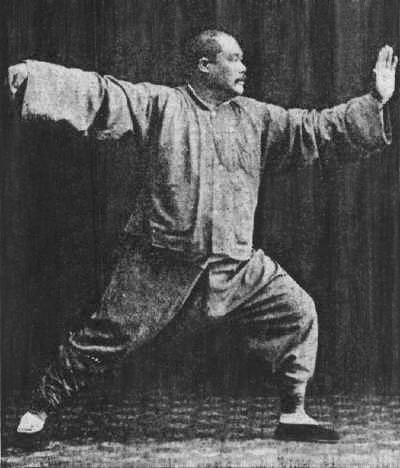

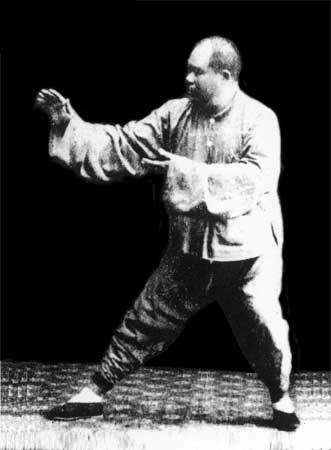

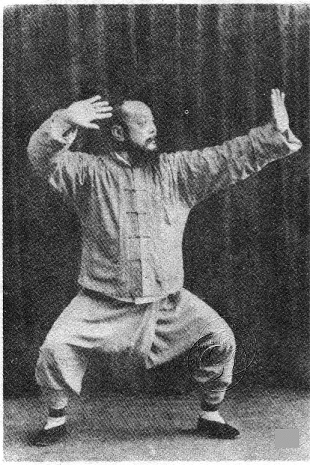

Personally, I can’t say I’m a fan of this method. To me it seems logical that in Tai Chi your body needs to have the sense of being stretched slightly from fingertips to toes at all times. I don’t mean stretched in a Yoga-like way, I mean that the skin needs to feel stretched over the bones and muscles, as if you’re made of rubber. Take a look at a picture from history of Wu Chien Chuan, of Wu style or Yang Cheng Fu of Yang style and I think you can see what I mean.

That way it’s like a guitar string being tightened so that it makes a sound when plucked in the middle. A lax string can’t be played. In Tai Chi that ‘middle’ is your dantien. If you’ve got a slight stretch on your body, from fingers to toes, then you can control movement along the length of this stretch using your dantien, so a movement of the dantien will naturally affect a movement of the extremities, if you let it.

The classics use the analogy of a bow, the most famous line being “Store up the jin like drawing a bow.”

Anybody can feel this stretch by adopting a Tai Chi posture and relaxing and trying to create an expansive feeling, but it gets stronger over time and with repeated practice. A lot of the chi kung exercises that come along with Tai Chi are designed to help you feel this stretch from fingers to toes, and help to make the connection stronger and more usable over time.

Chen Man Ching’s idea of Tai Chi seems different to me. It’s more like he’s got no arms and the jin is stopping in his shoulders, not reaching his hands. At least that’s how it appears to me.