I had an interesting chat with another Tai Chi teacher this week. Generally, Tai Chi teachers are nice people who have trained hard at something for a number of years and developed a lot of skill in it. They’re often not that into the martial side of the art, (even if they say they are), yet they’ve managed to pick up a lot of what I call “Tai Chi Miasma” along the way.

(If you want to know what a Miasma is, I do a podcast about the subject and how it reverberates through human history. Click the link above. A brief summation of Tai Chi Miasma would be, “a set of unconscious and often faulty assumptions about combat influenced by Tai Chi training”, but I’d also have to include a lot of Chinese miasma about yin and yang, qi and tao that was incorporated into Tai Chi by the influence of the Neo Confucian Zhu Xi amongst the intellectual class.)

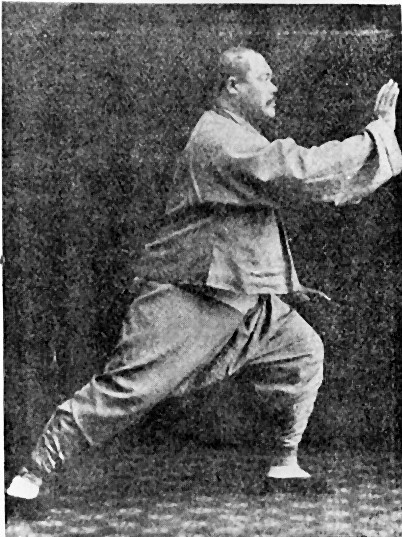

For example, I find that there’s a pervasive belief amongst Tai Chi practitioners that the fight is effectively over once they have taken your balance. They’ll say things like, “once I’ve got you off balance I can walk you around the room”.

I’m sorry to break it to you (pun intended) but no, the fight is not over just because you have broken my balance!

It’s not over even if you get me off balance and whack me in the face, unless I’m unconscious or too hurt to continue by your deadly 5 point exploding palm technique.

Yes, I’m sure you’ve seen your master controlling people with the lightest of touches and walking them around the room in a wrist lock or arm control of some kind, but that’s happening in a controlled training environment. In real life, it’s not like that.

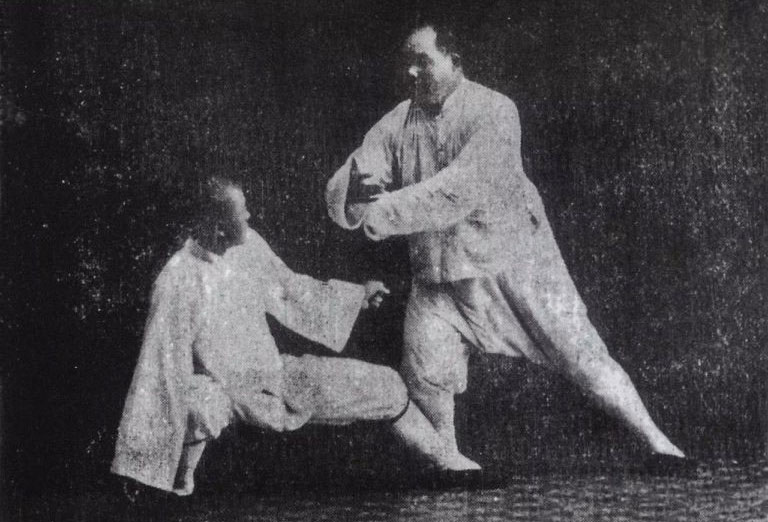

Just watch any combat sport with live training against resistance. Say wrestling or judo. The players are in a constant state of flux. They are losing their balance and regaining it over and over. Often they willingly sacrifice their balance for a superior position.

Judo. It’s crazy.

They get thrown, they get taken down, they get pinned, but they fight their way back up and go again. The fight is not over just because one person takes the other’s balance, however skilfully or with the lightest of touches they did it.

“Ah!”, they say, “but once you get them off balance it’s easy to keep them off balance. ”

No, no it’s not.

Just look at MMA. MMA is an even better example than pure grappling arts because it involves strikes. Sometimes the strikes are controlled and orderly, but a lot of the time, especially after people get hurt and tired, there are wild punches being thrown looking for a KO, resulting in people falling all over the place, people slipping, kicks missing, etc.

MMA. It’s painful.

The 80/20 rule.

In grappling sports, people spend a lot of time training what to do after the balance has been taken – or “finishing moves” if you like. That’s where 80% of the training is, because they know it’s not easy and they want to secure the win.

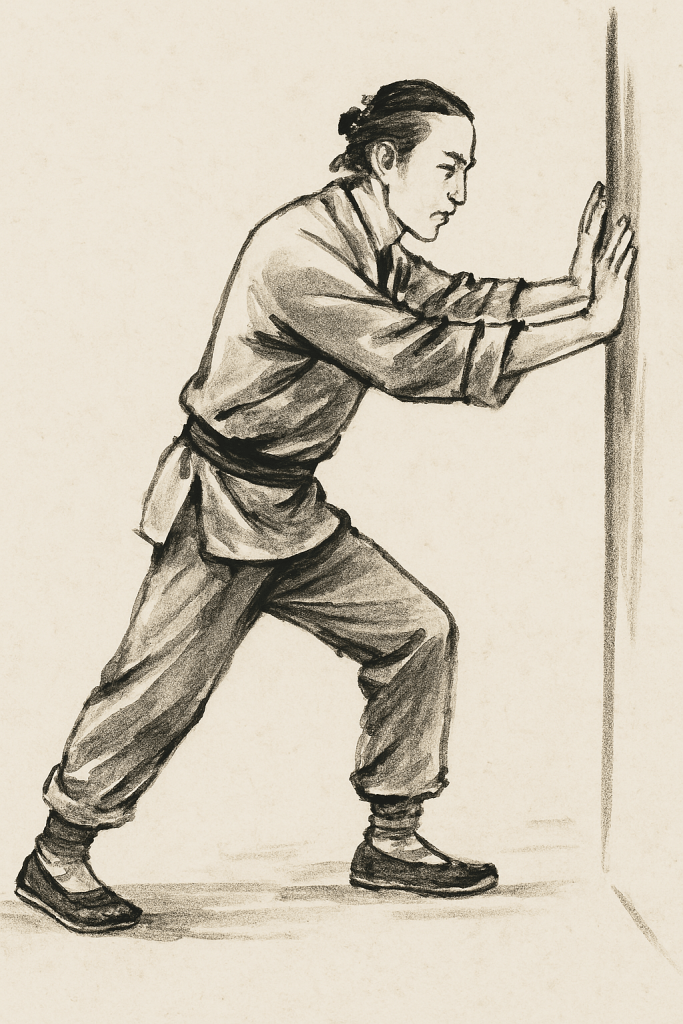

In contrast, Tai Chi partner work seems to be 80% about balance taking and 20% about what to do afterwards… if you’re lucky.

That’s fine if you are aware of that, but not fine if you then start to make grand pronouncements about what would happen in a combat situation because you’ve been told about what should happen next in the method you are teaching, rather than your direct experience.

Yes, I’m making a huge generalisation, and I’m sure it doesn’t apply to YOUR school. [wink emoji for sarcasm] But allow me the exaggeration to make my point.

By the way, I’m sure I have my own martial arts miasma too. We all do, but what I’m saying is that we should be aware of it.

Catch yourself saying these things about what should happen next, or what would happen next, if you can. Let your actions speak, not your words.

There’s nothing wrong with focussing on balance breaking. It’s fun, and skilful, and nobody is getting hurt, but also make it a point to spend significant time sparring with resistance.

It keeps you honest.