Learning how to extend the qi

When I’m teaching my Friday class one of the things I quite often say is “don’t look down” – however, like most of the short, pithy statements you hear delivered by Tai Chi teachers… it’s not really true. Rather, it depends on the context of what you’re doing. Let me explain.

Yes, generally speaking, you want to be looking at the horizon when doing Tai Chi because you want to keep your head and neck aligned with your spine. Specifically with the head and neck we are talking about the posture principle of ‘suspending the head’. However, there are times in Tai Chi, where it is perfectly acceptable to look down – particularly on moves where the direction of the application is down towards to the ground.

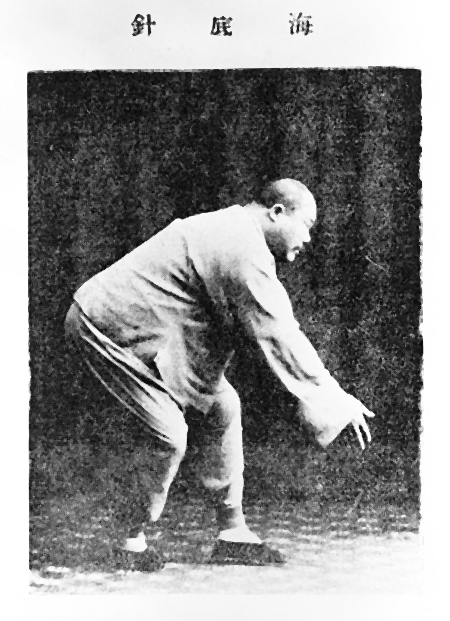

Like our White Crane Cools Wings, for example:

White Crane Spreads Wings from the ‘short short form’ I teach.

The reason I say “don’t look down” a lot when teaching is that people learning a Tai Chi form have a general tendency to look down (me included!). Generally as we age our posture seems to become more slumped forward, perhaps because we sit down a lot in modern life, but also because scanning the horizon for signs of danger has long since stopped being an evolutionary priority. We also use computers, phones and devices all the time, and they lead to a general posture of our heads being tilted forward slightly. This can result in people doing the whole Tai Chi form while never looking up from the ground.

Extending the qi

In Tai Chi you want to have a feeling of a slight stretch all over the exterior of the body at all times – that’s really what following the posture principles of Tai Chi gives you – things like flattening the lower back, rounding the shoulders and suspending the head. This is known as ‘extending the qi’ all over the body. When you stand in a Zhan Zhuang posture you can feel this slight stretch all over the surface of the body that the posture generates – it’s subtle, but that’s what you’re looking for.

Suspending the head is part of that extension of the qi over the head, and you can keep that extended feeling even when you glance down. What you definitely don’t want to do is break the alignment of the spine and neck, which is what typically people do when looking at their phone, or their feet:

Looking down at your phone. Photo by Thom Holmes onUnsplash

If you want a good fix for this then I find regular Zhang Zhuang (“post standing” or “standing like a tree”) practice is a good way to remedy this and retrain your head position on a subconscious level. Master Lam has a 10-day course on the subject.

The problem with looking down is that our head is rather heavy (between 2.3 and 5kg), and when you take your neck out of alignment with your spine your body automatically compensates for the extra weight that is pulling it forward (or you’d fall) and it does that by tensing some of its posture control muscles, particularly in the middle of the body, and that can interfere with the relaxation and freedom of movement we are looking for in Tai Chi. You also aren’t creating an optimal path for sending incoming forces to the ground or for sending jin up to the head. You are also not ‘extending qi’ to the head.

If you’re going to look down then you need to do it while keeping that slight stretch up the back of the neck and over the head.

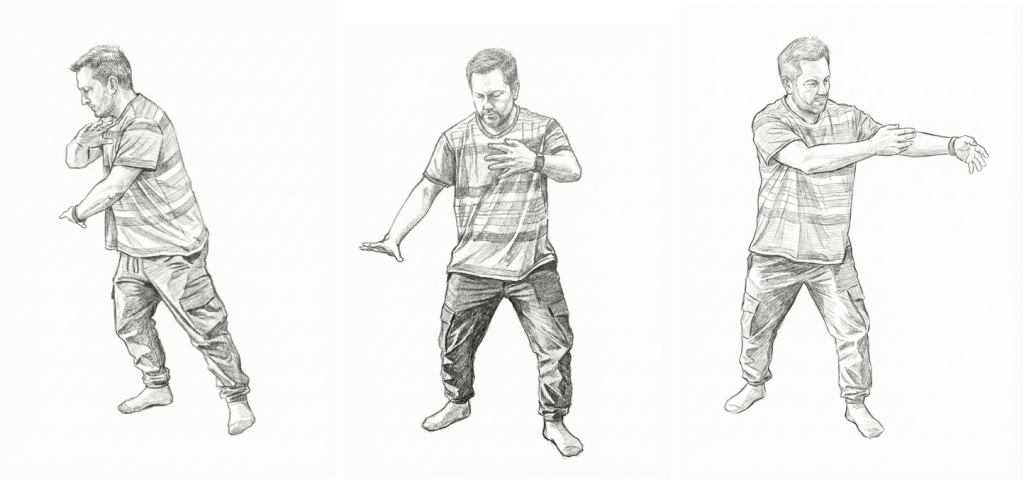

Ward-off and martial applications

‘Ward off’ is another example of a posture where I do look down, although it’s only briefly. I look down because of the martial application I’m thinking of. My active hand in that posture is first the back hand, which I’m using to send my imaginary opponent to the floor. The front hand can then be used as a deflector, so after I’ve dispatched the first opponent to the floor, I then look up and deflect the second attack, which leads into the ‘roll back’ posture.

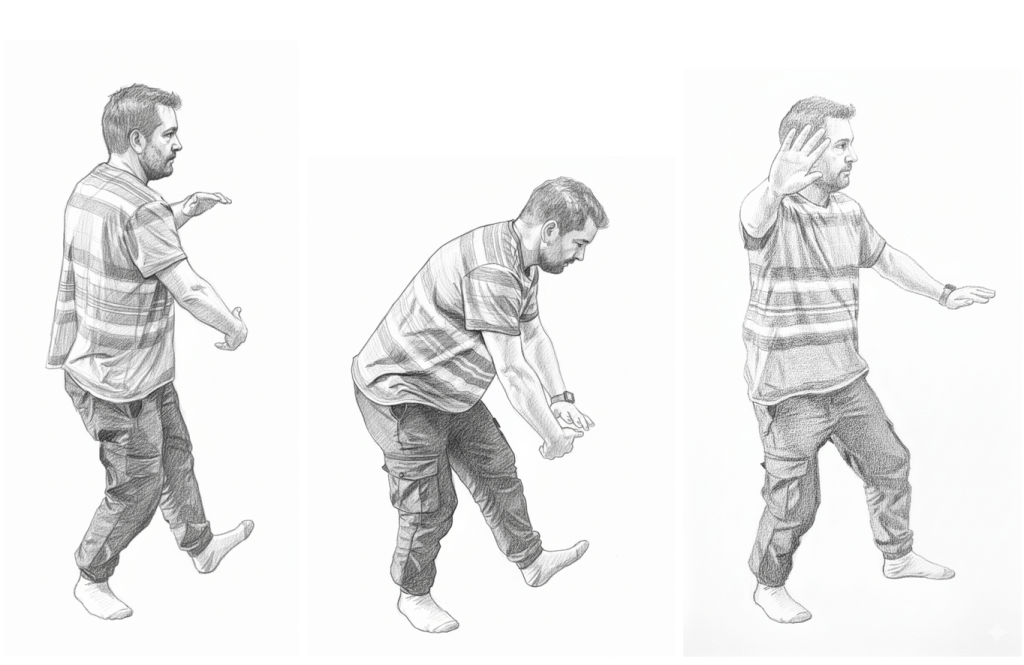

Here is the sequence:

In this sequence, the ‘ward off’ is the middle picture, and my focus is on my right hand pushing down from where it was in the previous picture, then in the next picture I refocus on the left hand deflecting, and getting ready to perform a ‘roll back’.

Here’s a much younger and hoplessly naive version of myself showing the marital application at around 19 seconds in this video:

As you can see, where you are looking in the Tai Chi form is dependent on what application you have in mind when doing the movement. So, while there are some useful maxims to remember in Tai Chi, such as ‘don’t look down’, it’s important that you know when it’s acceptable to bend the rules so that your Tai Chi becomes a living practice, with things done for a reason, not just blindly following the rules.