The age-old debate on sport vs self defence training opens up again, and this time, I’m in it!

“I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. If you had somebody who has only ever trained sport jiu-jitsu and they’ve done the most sporty of the sport jiu-jitsu – they’re only ever training berimbolos, crab rides and rolling back takes – that’s their whole game, but they’re training against resistance, and they compete, especially if they compete, they are 100 times better at self defence than a guy who just practices self defence techniques in isolation.” – Stephan Kesting

That’s a quote from the first part of this clip that has been making its way around the Internets from Stephan Kesting, one of the shining lights in the Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu community.

He goes on to say more, but the above quote is the essence of what he’s saying.

I completely agree with him, but not only that, I’m actually in the clip – I’m the guy with the glasses at the bottom of the screen.

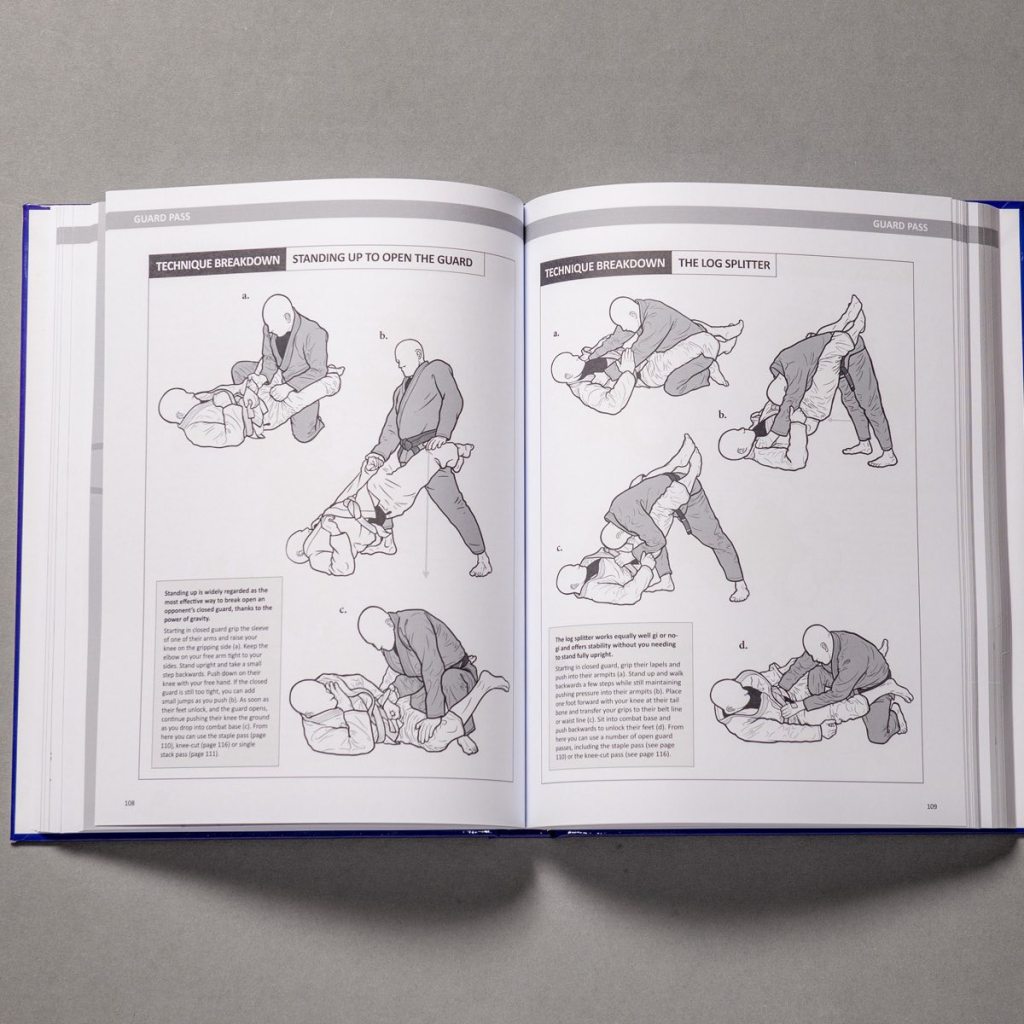

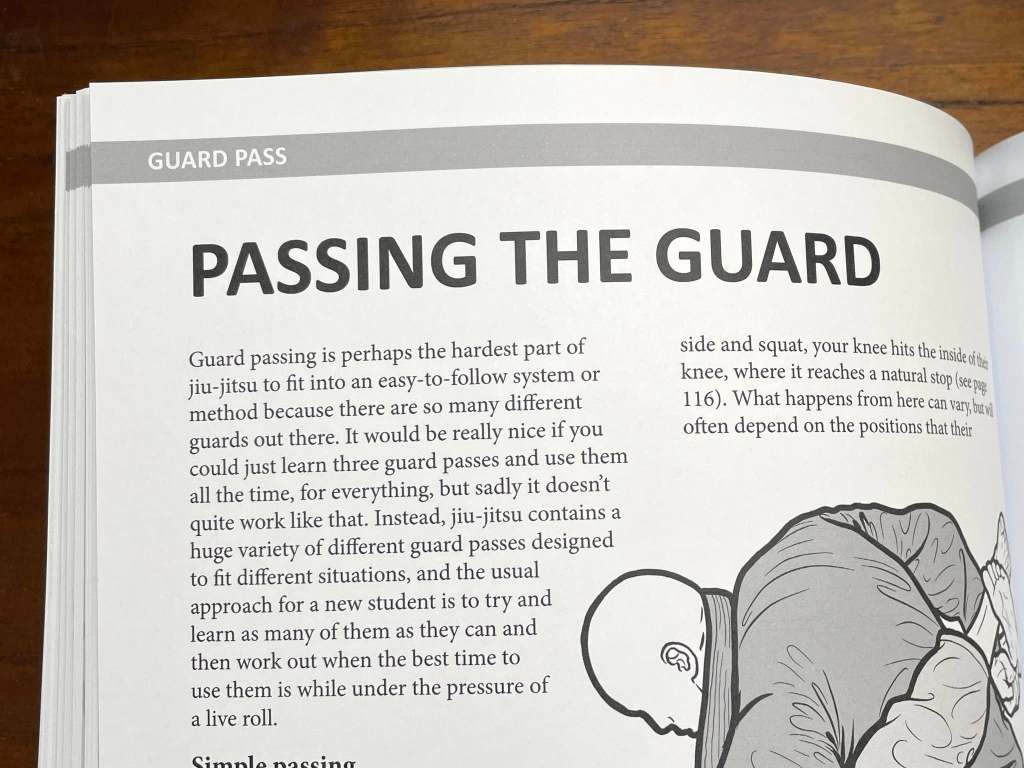

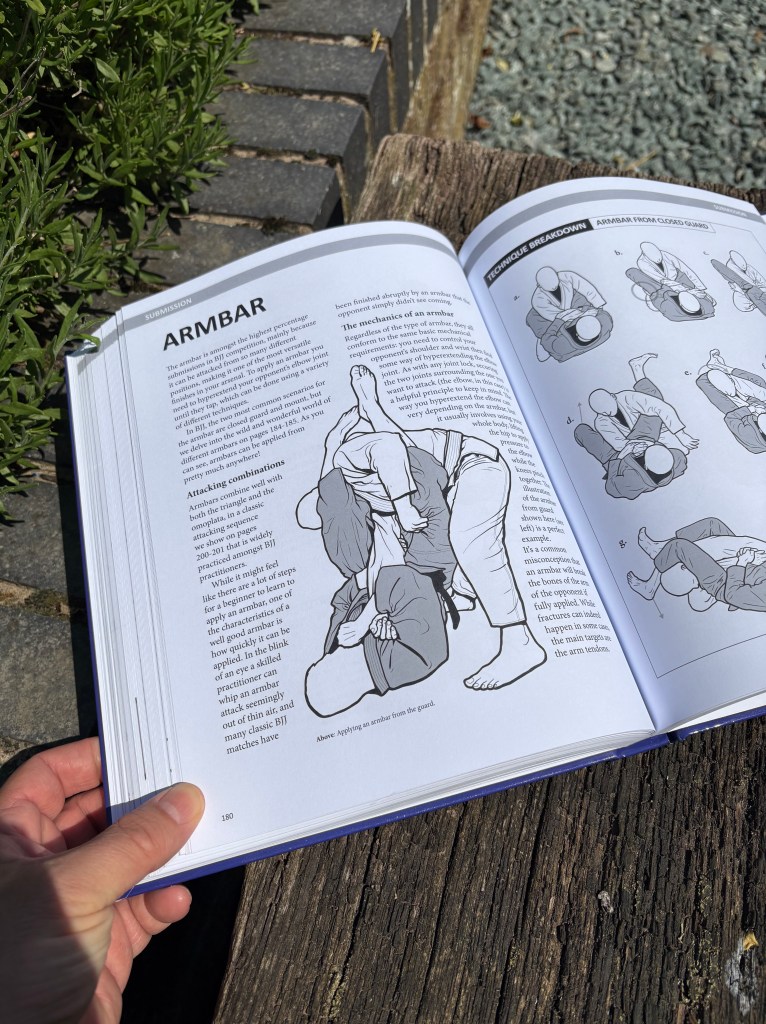

This clip was part of the longer podcast we recorded I recorded along with my writing partner Seymour Yang (Meerkatsu) with Stephan about our new BJJ book, which is currently being shipped out to people that brought the pre-order.

Incidentally, the book is not on sale anymore, that pre-order was a limited run, hard back, collectors edition. We’ll probably release a softback version in the future on a similar limited print run idea, but we haven’t decided for sure yet.

But back to the clip.

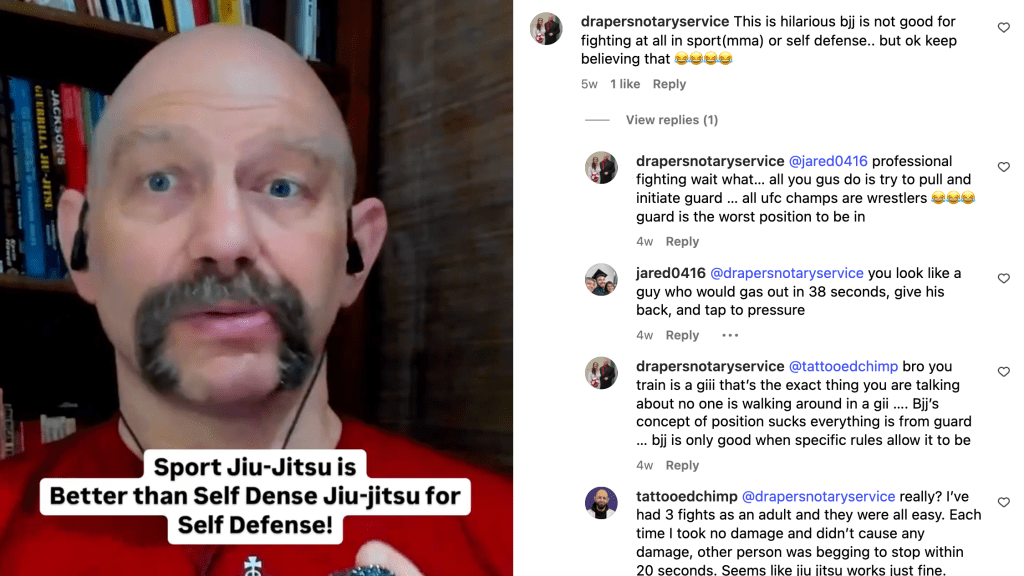

Obviously, because this is the Internet and people can’t read or listen to something without immediately copying and pasting their own opinions about what they think he said, or wrote. So, this clip caused a bit of a ruckus online, attracting comments such as:

“This is hilarious BJJ is not good for fighting at all in sport (MMA) or self defense.. but ok keep believing that “

“I don’t know not all fights end up on the ground right away. And no one’s is gonna wait for you to sit down and start fighting. My complaint with some of the sports jiujitsu has to be Takedowns, it’s like they forgot to do takedowns.”

Now on their own there is some merit to the points being made, however they don’t refer to what was actually being said by Stephan. Let me reframe his statement in the way that Bruce Lee used back in the 1970s with his article called “Liberate Yourself from Classical Karate”:

Stephan is saying that the spontaneity and natural reactions that ‘live’ training will develop is worth 100 times what you’ll learn by practicing ONLY dead forms.

That’s the point, not the applicability of BJJ to self defence or whether all fights end up on the ground. And obviously it’s not an either/or choice, and there’s a lot of grey area in regards to marital arts triaining, but that’s the crux of the matter

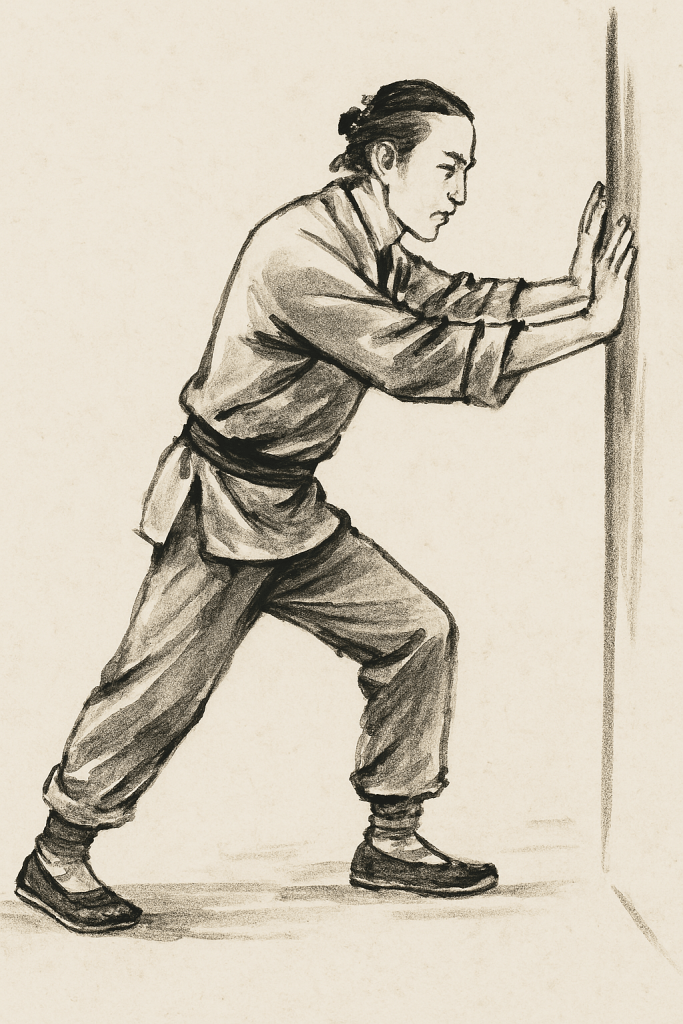

Bruce framed the argument around the idea of live, spontaneous training vs repeating dead forms. There are a lot of great quotes in the article by Bruce Lee, but here’s a couple I particularly like:

“It is conceivable that a long time ago a certain martial artist discovered some partial truth. During his lifetime, the man resisted the temptation to organize this partial truth, although this is a common tendency in a man’s search for security and certainty in life. After his death, his students took “his” hypotheses, “his” postulates, “his” method and turned them into law. “

“Prolonged repetitious drilling will certainly yield mechanical precision and security of that kind comes from any routine. However, it is exactly this kind of “selective” security or “crutch” which limits or blocks the total growth of a martial artist. In fact, quite a few practitioners develop such a liking for and dependence on their “crutch” that they can no longer walk without it. Thus, any special technique, however cleverly designed, is actually a hindrance.”

To me the argument that Stephan is making and the argument that Bruce is making are different aspects of the same thing. It’s the ‘learning to swim by never getting in the pool’ analogy all over again. You simply can’t learn to swim without getting wet, no matter how great your theory of swimming may be.

We would all laugh in the face of a theoretical swimmer who only ever practices on dry land and yet we tend to revere the opinions of the theoretical martial artist far too strongly, especially if they have a cool uniform and a black belt with lots of stripes on it.

Personally, I find that the less I practice sparring in a week the stronger the need for coming up with solutions for theoretical situations becomes in my mind. The more actual resistive sparring I engage in, the less my mind craves these sorts of questions. Instead, I’ve actually got something useful to be thinking about, like how I would do a technique from that last round better, or how I would escape a particular situation that actually happened, next time.

Just imagine if you haven’t done any actual sparring for years. There are plenty of ‘martial artists’ like this. Their heads must be full of theoretical knowledge, most of which probably wouldn’t survive an encounter with reality. And all of which can be silenced with just a few seconds of actual sparring practice.

Into BJJ and looking for Jiu-Jitsu gifts?