“Could you tell me if there is a specific exercise to raise the spirit of vitality?

Or could this be just any exercise at all rather than a specific one?

I have been learning tai chi and it talks about Spirit/Shen and its importance,

but I haven’t a clue exactly what it means. I know to feel full of spirit means you feel on top of the world and ready for life- this is what I would like to feel.”

Well, that’s a tricky one to answer. You have to ask what is meant by “spirit”. In the Mongol language, for example, there are a whole plethora of words that in English would translate in “spirit” and they all mean something slightly different. The Chinese word “shen”, I think, could be translated into several different English words depending on context. In English we have to add more words to a sentence containing “spirit” to add context. For example, “spirit of vitality” – this would be the sense of feeling full of energy and ready to face the world that you talk about. But there are other words that we translate as “sprit” that have all sorts of meanings, from the mundane to the profound – and all slightly related. For example to “raise the spirit” can mean something as mundane as keeping the posture upright with the head up, or as profound as the creative realm of the tree of life.

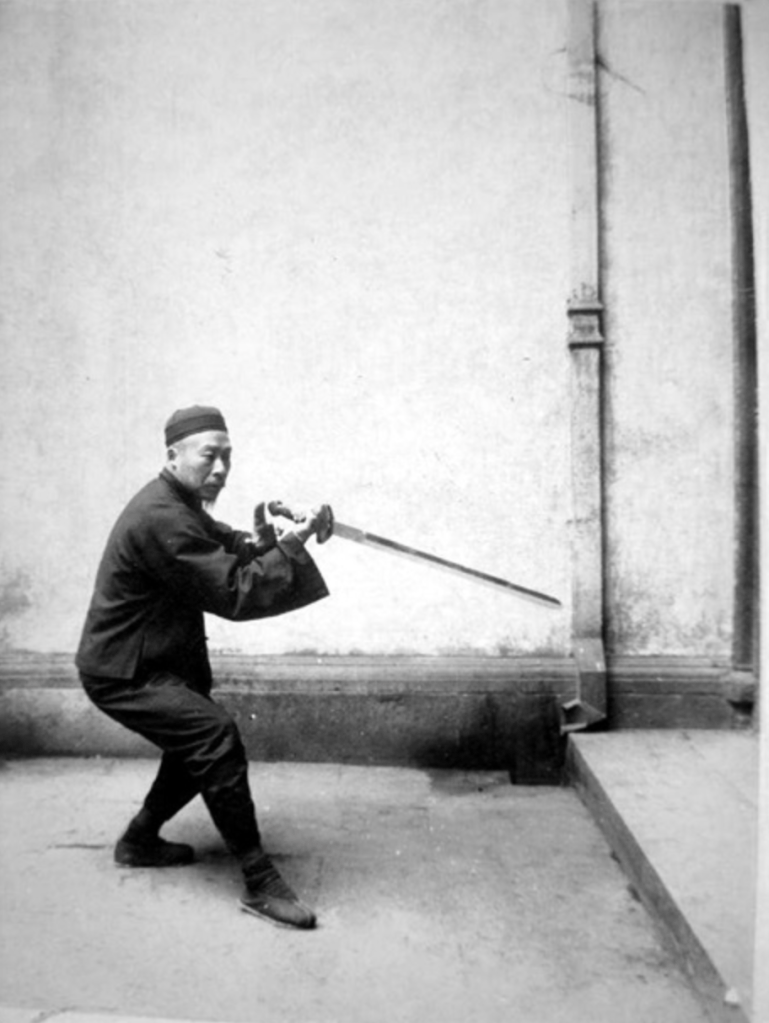

This idea of being upright (physically, mentally and spiritually) is a big thing in Tai Chi – we are told to “let a light and intangible energy raise to the head top” in Yang Cheng-Fu’s 10 Important Points.

So, to get to the other part of your question – how to do it. There is no specific exercise for raising the spirit of vitality. Rather, it is a part of the postural requirements of Tai Chi, so it should apply in all exercise orientated towards Tai Chi practice. You want to feel as if your head if being pulled up by a thread from the crown point (between the tops of the ears). The result should be that the back of your neck gently lengthens and the chin tucks in. As always, you don’t want to achieve this posture with force, so don’t push your head into it. You should find that if you stand, focus on your breathing, generate that lightweight observation of self that is required in Tai Chi, your head and neck posture should naturally want to assume this posture.

Everything in Tai Chi works together. If you are breathing well, then it will encourage your posture to be upright and strong, which in turn will encourage you to ‘raise the head top’. If you can remove stress and tension from the body then the weight will sink down simultaneously, so you should feel strongly rooted into the ground and drawn up from the crown at the same time. These two pulls in opposite directions provide balance. You are separating yin and yang in the body – again, another part of the Tai Chi process.

I hope that helps.