The power of relaxation

Mike Sigman’s post on qi has made me want to think more about jin and qi again. I realise I haven’t been posting about it very much recently – partly because I’ve been distracted by writing a book about BJJ – but now the book is finished it’s time I came back to the subject. I read another post Mike made recently on his 6H group about pushing against a wall, which I think is a brilliant idea, because it’s so simple.

In a way this post is just me writing it out in my own words as an exercise, so I can understand it, and contextualise it a little more in terms of my tai chi practice.

Pushing is a big deal in tai chi because it features so prominent in the form – one of the four ‘energies’ of tai chi is called push in English, which (as I discussed with Ethan Murchie in my last podcast) is confusing since the translation of “an” into English is more accurately to “press down”, which isn’t what the push posture in tai chi looks like, or how you’d push a wall.

Pushing is also part of tai chi’s two person exercise, tui shou – “push hands”. So most tai chi people are pretty familiar with the concept of pushing.

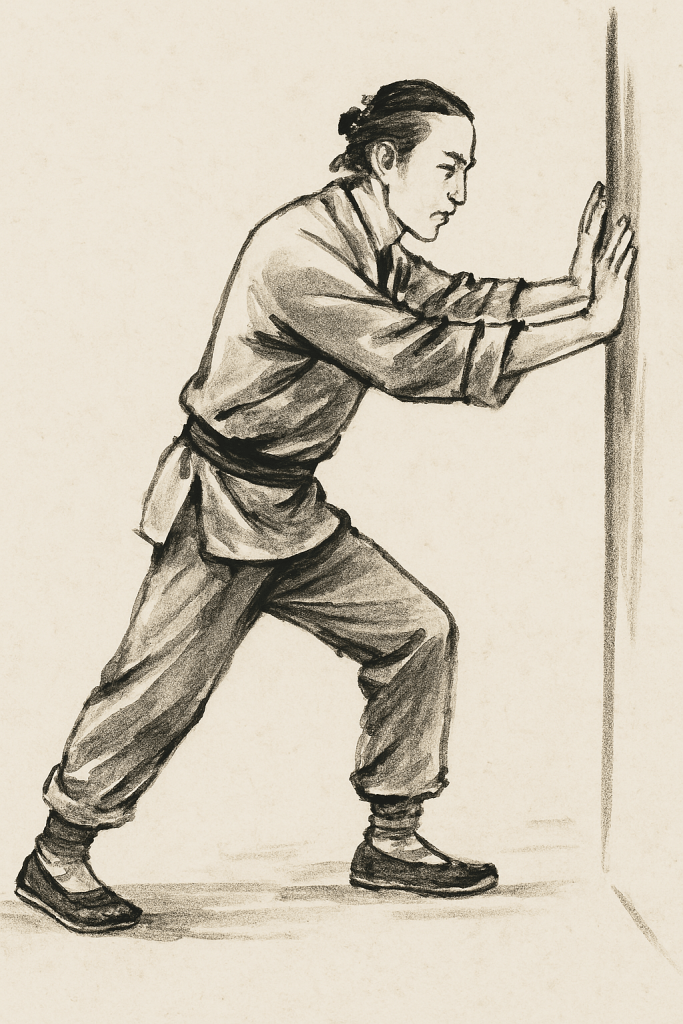

Now imagine you are pushing against a wall and somebody asked you to push harder. Most people would simply push harder with their arms and lean harder into the wall. What you’ll feel when you do this (try it) is that it pushes your upper body backwards and away from the wall quite a bit because it’s impossible to push hard with your arms without introducing excess tension into the system.

This is the “you’re using your shoulder too much!” criticism that a lot of tai chi teachers sling at their students, without really explaining how not to push using the shoulder.

So, let’s look at exactly how you could push harder without using the shoulder.

The only another way to increase the power of your push is to increase the downwards power through your legs. Now, it’s pretty hard to push downwards with your legs, since we have nothing above us to push off from if we want to push downwards. Instead, all we have in a downwards direction is gravity, so how do we use that gravity power? The answer is to relax and sink down into your legs harder.

Put your hands on a wall and try it.

As you sink and relax more through the legs you should feel the power in your arms increasing.

What you’ll notice is that you have to internally align your body correctly for this power to reach your hands. The good news is that you don’t need to think very hard to do this, you can just feel how you need to arrange yourself and your subconscious will do the rest. But you need to properly relax. If you tense up parts of your body – your shoulder being the main culprit – the power won’t slow smoothly and uninterruptedly through the body to reach its destination.

At this point you should start to realize why the word relax (or “sung” in Chinese) is said so often in tai chi practice.

That path from floor to hands is what you’d call a ground path, or a jin path. And the force you are channeling into your hands is known as jin in Chinese. The usual English translation of jin that you see used is “refined strength”.

Again, don’t get hung up with where the path goes through the body, just where you want the force to go.

You should also notice that as the jin force in your arms increases, you don’t get knocked or pushed backwards as easily as you did when you were using brute strength, because there is less tension in your upper body.

Obviously you are not going to push a wall over! But you can now feel the forces in your body that we should be dealing with when doing the tai chi form, and hopefully when you do “push” in the form, your push will now be a little bit different, more refined, a little less clumsy and a lot more tai chi-like.