Religion, Theatre, and the Chinese Martial Arts, by Daniel Mroz

My good friend Daniel Mroz’s new book Resonant Space is out now! Daniel was the first guest on my podcast — back when I had no idea what I was doing with recording and editing audio, so it sounds pretty bad compared to my more recent efforts. However, what he talked about remains as insightful and up to date now as it did then. This book takes his ideas even further.

Here’s the blurb:

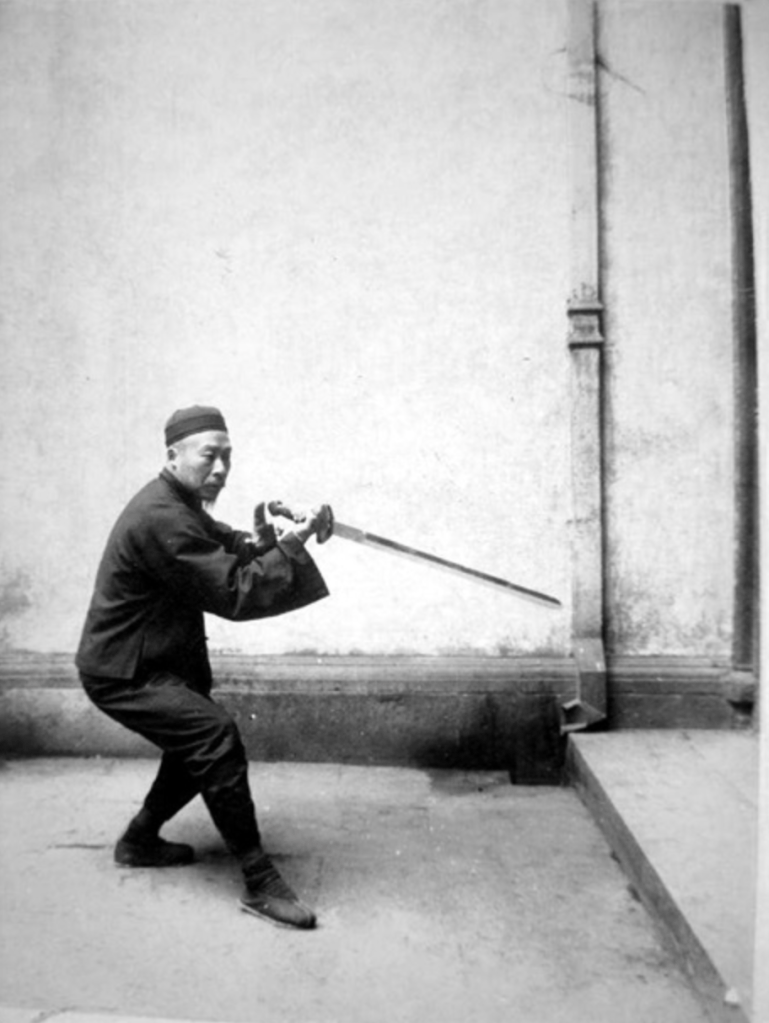

“Resonant Space constellates the martial, ritual, and theatrical elements of the Chinese martial arts with the practice of contemporary theatre and dance. This interdisciplinary approach blends the embodied experiences of the author, a lifelong student of the Chinese martial arts and a theatre director and dance dramaturg, with the study of Chinese cultural history. This is a work for scholars and practitioners of the Chinese martial arts, of contemporary dance and theatre, and for scholars of Chinese religion and cultural history.”

The best bit? You can read the whole book for free digitally, or buy a printed version for a reasonable price.

If you are at all interested in the intersection of Chinese martial arts, magic, theatre, military methods, violence, dance, self defence and religion, then you can’t miss this. I have read bits of this book already (it’s excellent), but I haven’t read it all yet, so I’m yet to appreciate it as a whole, and to see how he makes all the pieces fit together. I’m very excited to finally get to read the complete thing.

If you’re a practitioner of Chinese marital arts, then I can guarantee that this book will make you think. In good ways. There’s almost an embarrassment of riches packed into every page. So, rather than attempt to describe it, I thought I’d just throw three random quotes at you from the first chapter of the book, without context. Hopefully they’ll make you want to find out more.

“In the Chinese martial arts and in military strategy more generally, excellence in fighting is secondary to trickery and wisdom.”

“Perhaps the most famous failure of war magic was experienced by the Yìhéquán 義和拳 fighters of the Boxer Rebellion of 1899, who discovered they were not impervious to the bullets of Western colonial powers.”

“Given its spectacular nature and emphasis on dramatic fights, it comes as no surprise that Chinese theatre, or xìqǔ 戲曲, employs many training methods that are virtually identical to those used in martial arts.”

Again, you can read the whole book for FREE from Cardiff University Press as a PDF, or you can buy a printed copy for a reasonable price. Don’t miss this!