Xing Yi is one of the oldest Chinese martial arts that is still practised today, and so naturally it has attracted a large variety of writings over the hundreds of years of its existence. These various writings can be found scattered about in different lineages and books, but now Byron Jacobs has collected them together in one weighty tome – Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit – and included not only the original Chinese texts, but also his own English translation and commentary on them.

Originally from South Africa, Byron is a student of Di Guoyong of the Hebei lineage of Xing Yi, and lives and trains in Beijing. At one time he was a member of the technical committee of the International WuShu Federation, so he has been able to meet and talk to practitioners of other martial arts and Xing Yi lineages. He runs the Mushin Martial Culture website that offers online tuition, as well as provides excellent YouTube videos on all aspects of Chinese martial culture, history and practice.

(Full disclaimer for this review: I’ve known Byron for years, and while we’ve never met in person I’d consider him a friend. He’s been a guest on my podcast and I’ve been on his.)

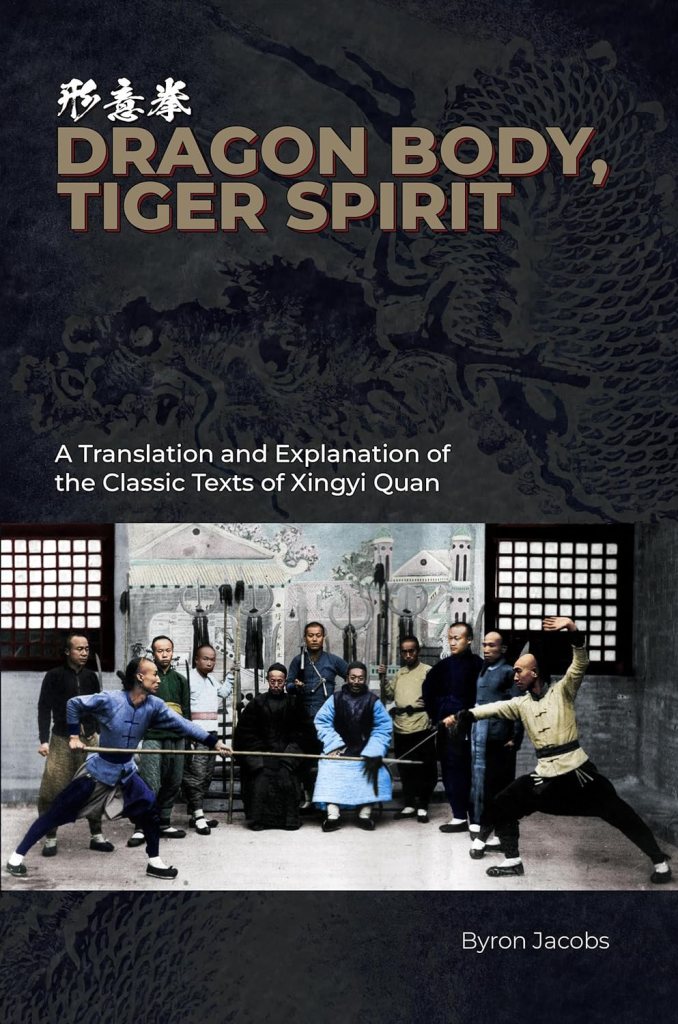

The cover

Being interested in design, I always like to spend a bit of time talking about the cover of a book in my reviews, but in this case it’s not really an indulgence because discussion of the cover is properly warranted. Not only is it well designed but it contains a fully colourised reproduction of the famous black and white photo of Xing Yi masters Guo Yunshen and Che Yizhai, taken when Guo visited Che’s martial arts school. Now, since this is the only picture that can reliably be said to exist of Guo Yunshen, it has always been treasured by practitioners in the Hebei lineage of Xing Yi, of which I would count myself as one. Colourising the famous photo is an audacious and brilliant idea. The colours and shading on the faces in particular all look natural and really bring Xing Yi to life as a living breathing art practised by real people, rather than an ancient art lost to history. Did Guo Yunshen actually wear blue robes? I don’t know, but he looks great in them.

Incidentally, the photo is misleading, because the martial arts display Che and Guo are watching is definitely not Xing Yi. Che and Guo are the seated older gentlemen in the centre, watching two performers of what looks like a more Shaolin-derived art, or even a theatrical performance. The stage they are sitting on, complete with performers doing martial arts, and a painted city background behind them makes the whole thing look very much like a Chinese theatre.

What’s inside

The meat of Dragon Body, Tiger Spirit is the collection of all the classic writings on Xing Yi, including a lot of the stuff that came out during the Republican-era martial arts manual-writing craze, as well as older material. Everything is provided in original Chinese characters first, then as a translation into English and finally there is a commentary by Byron which explains what the classic is about. For me the most important classics in the Xing Yi corpus are Yue Fei’s 10 Thesis, since these are amongst the earliest writings on Xing Yi, and a lot of the other writings are based on these, but rest assured they’re included here. In fact, there’s everything you could want, including the Five Elements Poems, Cao Jiwu’s Key extracts of the 10 methods, the 12 animals poems and more. There’s also a section called “Nei Gong Four Classics”, which is a supplementary text included from the Song style lineage of Xing Yi. The classics are bookended with two different sections – the book starts with a short article about the history of Xing Yiquan, written by Jarek Szymanski, which aims to dispel some of the myths that have built up around the art, and ends with some well-researched biographies of famous Xing Yi masters written by Byron. As a practitioner of Xing Yi you’ll find these biographies useful because the names of old masters often crop up in Xing Yi discussion.

I can’t speak for the quality or accuracy of the translations themselves since I’m not a Chinese writer or speaker, however my impression through comparing Byron’s translation here to others is that Byron has used his martial arts knowledge, and specific Xing Yi knowledge to present what he thinks the real message that the classics are trying to be convey is, rather than go for a literal translation each time. This is the best way to approach martial arts texts, as often a literal translation will sound nonsensical, and just make an English speaker scratch his or her head.

Having the actual text of the classics all gathered together in one place is an invaluable resource for any Xingyi Quan practitioner. That alone makes the book worth getting, but what really tips the balance is Byron’s commentary. He’s always clear, down-to-earth and practical. He does his best to interpret old texts that can often be esoteric and difficult to understand into something that makes sense to practitioners living in this day and age. Apparently, this book took him 10 years to complete, and you can see why. He must have spent a long time agonising over his translations and commentary before committing to a final version – nothing here seems rushed, hurried or half-baked. Everything has been carefully considered.

The casual reader, or beginner in Xing Yiquan, needs to be aware that this is not a “how to” manual – a lot of the Xing Yi classic are about things like endlessly dividing the body into sections and saying how one part works with another, which is not much use to you if you just want to learn how to do a Bengquan. They are full of things like “the eyes connect to the liver, the nose connects to the lungs” – i.e. things that aren’t that much use for practical application. There is a lot of this stuff to wade through if you are going to read the book from start to finish in full. However, having said that, Byron’s commentary on the 5 Element poems (the section of the book that deals with the Xing Yi 5 Element Fists – Pi, Beng, Zuan, Pao and Heng) is so detailed and practical that it does almost function as a bit of a How To. If you are in the process of learning Xing Yi you’ll find this section invaluable. You’ll learn where to put your elbow, fist, feet and how to move your body. And there’s a picture of Byron performing each fist, too.

I did find myself having small differences of opinion with Byron’s commentary on occasion, but it’s always over very small details or emphasis, and it feels like nit-picking to list them all, but I think it highlights an important point, which is that translation relies on interpretation and because we come from different lineages of Xing Yi I think it’s only to be expected that we’d have slightly different ways of looking at the odd thing. And you too, dear reader, will probably have small differences too, if you are already a Xing Yi practitioner. If there weren’t small differences between lineages, then there wouldn’t be different styles of Xing Yi in the first place.

My favourite part

For me the best part of this book is the 12 animals section. I’ve always found the 12 animals to be the most fun part of Xing Yi, and if you’re a fellow 12 animals fanatic like me then you’ll love this section. It’s also the largest section of the book, and is illustrated with pictures of the animals being described. For each animal there is a poem written by Byron’s own teacher Di Guoyong, followed by a discourse on the animal written by Xue Dian, taken from his 1929 Republican-era manual “Discourse on Xing Yi Quan” (which was written at a time when it had become popular to include aspects of Chinese philosophy and medicine in martial arts writings). Byron translates both and provides his own commentary. There’s such limited writing about Xing Yi animals available that it’s fantastic to hit such a rich vein of Xing Yi animal discussion. My experience has been that every lineage of Xing Yi has slightly different ideas about what a few of the 12 animals are, particularly “Tai” (which gets called everything from hawk to ostrich and phoenix) and “Water lizard” which gets called a turtle, an insect or a crocodile by some. The view presented here is Di Guoyong and Xue Dian’s (amongst many others), that Tai is a small hawk and Water lizard is a mythical creature being one of the 9 sons of the dragon that had a turtle’s shell.

It’s the spirits of these animals that infuse all Xing Yi practice – even if you’re doing the 5 elements or SanTi, you are still admonished to observe ‘bear shoulders’, ‘tiger head embrace’, ‘dragon body’, ‘eagle claw’, and ‘chicken leg.’ So, it’s great to see such a large section of the book, which gets its name from the dragon and the tiger, devoted to them. Di Guoyong’s poems and Byron’s commentary here are especially valuable, particularly in regard to the intent and particular features of each animal.

Should you buy?

As always with Chinese martial arts classics, these are not writings you read through once and put on the shelf, having absorbed all their insights. Instead, you need to return to them again and again over the course of your life and dip in and out. You’ll find this reinvigorates your Xing Yi practice and each time you re-read the same section you’ll discover new insights. Picking the book up and turning to any page, it’s not hard to find something to be inspired by and to get you motivated to go outside and practice.

If you are a Xing Yi practitioner then having everything here in a single book will prove invaluable to you and Byron Jacobs has done every practitioner a great service by completing his magnum opus. Even if you are a Tai Chi practitioner, I’d still say you should get this book, as many of the ideas contained in all internal arts found their first flourshings of life in Xing Yi and the Xing Yi classics. Highly recommended.

Rating: 5/5

—

Where to buy::

Direct from Mushin Martial Culture

If you want to find out more about the book then I’d recommend listening to Byron’s interview about this book on Ken Gullette’s podcast.

You can also buy a reproduction of the cover photograph from Byron’s Mushin Martial Culture website.