One of the things I like to do when watching UFC fights is to try and analyse what the fighters are doing in terms of Xing Yi’s 12 animals. Now, I’ve got at least one friend who hates when I do this because he believes it makes people think that by practicing a few Xing Yi moves twice a week in your back yard you can somehow be on the level of professional MMA fighters. Yeah, I get that. Comparing martial arts can easily lead to delusion… however, my No. 1 one rule for The Tai Chi Notebook is this: this is my blog and I can write what I want! So, I’m going to do it anyway. But also, I genuinely think that if you’re a Xing Yi practitioner yourself, then trying to analyse MMA fighters in terms of the 12 animals is a really valuable hobby to get into. It will increase your understanding of not only the animals, but also of fighting itself.

Viewed through the modern Xing Yi lens (by modern, I mean, post Boxer Rebellion, from the early 20th century onward) it’s popular to understand the 12 Animals of Xing Yi as merely variations on the 5 Elements. This approach is indicative of the reductive, simplistic, winds of change that blew through Chinese martial arts over that century. It’s not a wrong view technically (the 5 elements are the basics, so of course they are inside the 12 animals), but it’s also a huge misunderstanding. The 12 Animals are more than just variations of the 5 Element fists, they are older and contain the essence of the art. They’re a continuation of a tradition that started back in the Song Dynasty. If you really want to understand that point of view then I’d point you towards the History of Xing Yi series we’ve been doing on the Heretics Podcast for a few years now – and is currently up to part 15, about to start the Ming Dynasty section.

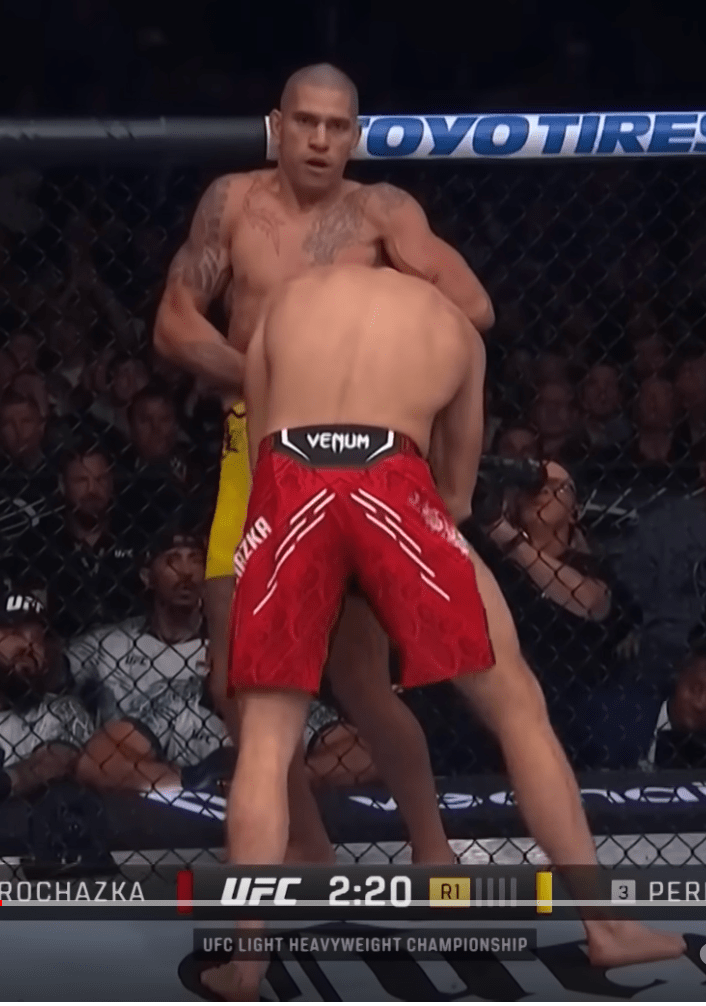

But coming back to the present day, last week saw Alex Pereira vs Jiri Prochazka for the UFC Light Heavyweight belt at UFC 295. It was a great fight resulting in a knockout for Pereira, but honestly it could have gone either way. There was some debate about the finish being an early call from the ref, but Jiri himself said he was out cold, so it was fair. Highlights here:

Looking through my Xing Yi lens at what the fighters were doing, UFC 295 was a good one because it was very clear what animal strategy each of them was using. (Obviously, neither gentleman has probably ever heard of Xing Yi, however, like I said earlier, I’m simply using the 12 animals to analyse fighting styles.)

Swallow (yan xing)

So, on one hand we have Jiri Prochazka (red shorts) whose attacks frequently go from high to low:

He kicks high to the head, then kicks low to the ankle:

(Obviously a lot, but not all, MMA fighters kick to both heights, but it’s the alternating way he does it, as a strategy, that I’m interested in. It’s not the techniques that make something an animal style, it’s the intent and strategy behind them, but also certain styles lend themselves naturally to certain techniques – which is a subtle point)

He dummys a wrestling shot low but then comes up with an upper cut.

His preferred range is long, and when he punches he throws arcing punches that start low, go high and finish low:

To me this is clearly a Swallow strategy. Swallow is a bird you wouldn’t normally associate with fighting, but it aggressively hunts insects on the wing, and defends its nesting location by dive bombing potential intruders, including humans! Its characteristics are swooping low then going high, particularly over water and “swallow skims the water” is a name often given to a popular swallow movement in forms in Xing Yi, Bagua and Qigong. But the swallow is also famous for its absolutely beautiful aerial acrobatics that are always elegant and graceful.

Chicken (ji xing)

But let’s get back to UFC 295. In contrast his opponent, Alex Pereira is famous for his minimal movement and crushing low calf kicks. There’s a great clip of him playing about with UFC commentator Daniel Cormier taking his low kick:

A native of Brazil, Pereira is also famous for his indigenous face paint he wears to the weigh in events:

You can see his famous calf kick in action in UFC 295, completely taking Jiri off his feet:

What’s remarkable about the Pereira calf kick is how little wind-up there is, which makes it hard to see coming – he just snaps it out. He does three identical kicks in a row in that part of the fight – the pictures above show the first – but all three hit home. His punches are delivered in the same way – the hand just snaps out with almost no telegraphing movement at all. You can see in the screen captures above of the kick that his body stays facing the opponent at all times. They don’t look like powerful shots, but you can see the deadly effect they have on his opponents. That very tight coil in his body around the spine that he’s using to pop his kicks and punches out is absolutely indicative of Chicken xing. “Chicken shakes its feathers” is a characteristic move of the animal found in Xing Yi links (forms) and somewhat resembles the Fa Jing expression that you see demonstrated in Tai Chi styles:

Chicken step

When Pereira defends he is using footwork to evade rather than ducking his body – in fact, he stays very upright and his hands are kept high and defensive, just like they are in Xing Yi Chicken, which relies on footwork for evasion.

The blows which set up the finish from Pereira were so fast and minimal they were hard to see in real time, but it was a counter 1-2, again delivered with that very upright body with the hips underneath the shoulders that is so characteristic of Chicken:

The very tight techniques of Chicken in Xing Yi are very metal in nature – sharp and cutting.

A perfect example of this Chicken style applied to MMA is the standing guillotine. When somebody shoots in for a takedown, wrapping the neck and using your hips to stand tall, with a narrow base is a very chicken-like technique. In fact, Pereira almost finishes the match with Jiri earlier with one:

Here’s a video of me doing some Xing Yi Chicken:

Another thing Chicken (done by humans) is famous for are the knee strikes, which in real chickens are enhanced by the spurs it has on the back of its legs, and elbow strikes. You see this with fighting chickens especially. My teacher always said that the martial art that most resembles Xing Yi Chicken is Muay Thai, which is famous for knees and elbows.

The finish in UFC 295 was delivered by downward elbows from Alex Pereira and he has finished UFC fights with his famous flying knee before, delivered here in a way that looks very similar to the knee strikes in the Xing Yi link I do above:

Hopefully I’ve made my case.

To repeat: I’m not saying something simplistic like, “UFC fighters are doing Xing Yi”, but that as a tool for analysing fighting styles, I find Xing Yi really useful and the 12 Animals remain really fascinating.

A bit of homework for you…

Finally, I want to leave you with a bit of homework – also on that card that night at UFC 295 was British heavyweight Tom Aspinall. He managed to secure the interim heavy weight championship belt that evening. To me he’s a clear example of another one of Xing Yi’s 12 animals. The question is which one? You have 10 to choose from! Post your answers, compete with your reasoning, in the comments section below and I’ll give a prize for the correct answer (correct according to me, anyway, and I am the final word in this 😉 ).

Have a watch here:

Swallow Photo by Rajesh S Balouria: https://www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-of-swallow-17484064/

Chicken Photo by Luke Barky: https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-chicken-on-a-concrete-pavement-2886001/