So, in my original post about using the Xing Yi 12 Animals to anaylse the fighting styles of modern MMA athletes (I know, it’s a small niche, but hey, I’m the only one in it!) we looked at Alex Pereira vs Jiri Prochazka and I speculated that they were good examples of the Chicken and Swallow Xings respectively.*

I left the reader with a question at the end… I asked them to take a look at another fight on the same UFC 295 card where British heavyweight Tom Aspinall took the interim heavyweight belt by defeating Sergei Pavlovich. The question was what animal style could we say that Tom Aspinall was a good example of. Take a look at the fight before reading further if, you haven’t already.

So, nobody decided to answer in my comments section but I got a few replies in private groups on Facebook, etc. One person got it half right, but they mixed two animals together in their answer, and only one was right. Interestingly most people seemed to opt for Tom being a rather large Monkey (Hu Xing). I get why, Tom is clearly bouncing in and out on his toes, despite being a massive human, but really that’s where the similarity with monkey ends. Monkey would try to attack from further out than Tom is standing, or from further in – it’s a very ‘in your face’ animal, but also a joker and a trickster. Taking pot shots, then running away. Remember the classic Monkey vs Tiger fight video? That’s Monkey. I can think of at least one modern MMA fighter who is a classic monkey – I’ll post about him in the future.

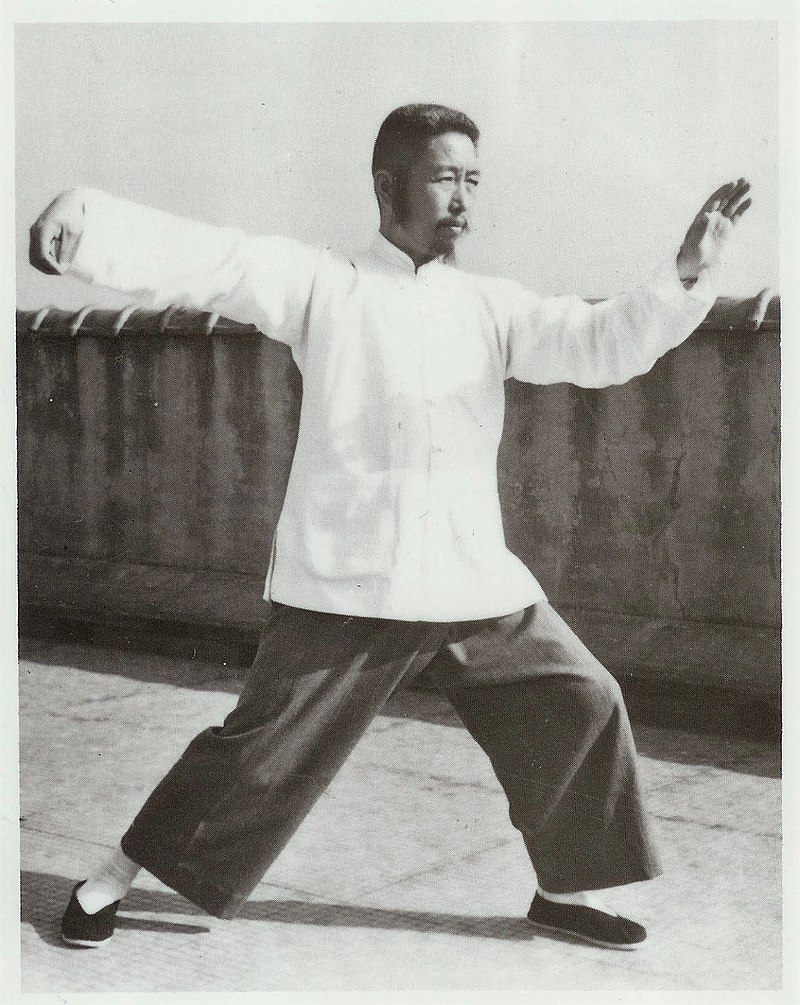

This charming man

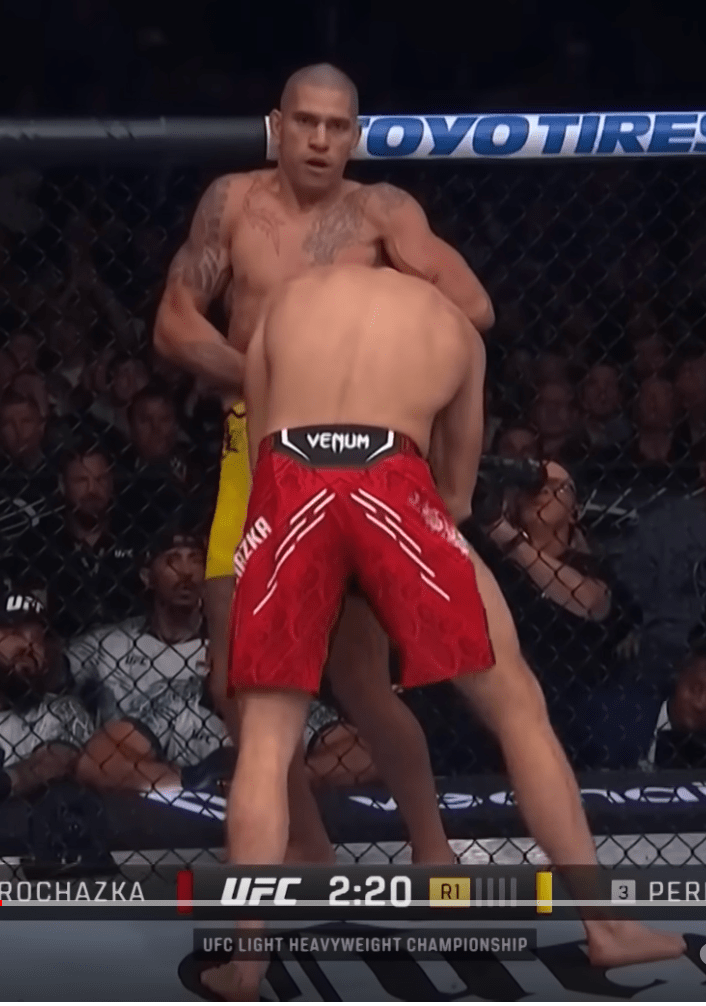

So, let’s look at what Tom actually is. He’s 100% Snake because Snake has Yin and Yang aspects. The key feature of snake is a coiling body, which can be used for either very quick strikes (Yang snake) or wrapping and coiling actions (Yin snake) for defence and grappling/locking. You can see this defensive coil aspect (Yin snake) particularly well when Tom is defending. There’s a little section in the round where he slips punches from Sergei while he coils and winds his body as he circles off – this is classic snake behaviour – just imagine if you were stupid enough to try to grab an angry snake by the neck – it would bend and coil around your hand, particularly if it was a python.

Snake’s are very aggressive, successful predators dating back to the time of the dinosaurs, and they’re always sensing forward, flicking out their tongue, and of course, they have the famous (and sometimes) venomous bite. When a snake bites the action is incredibly fast – you’ll notice that when Tom flicks out his jab the speed catches Sergei completely by surprise. For a big man he punches very quickly. The finish is so fast it’s hard to see, but Tom punches Sergei twice before Sergei can even react, steps back, looks at him, then punches him again sending him to the canvas:

Throughout the fight, Tom is flicking out single jabs and single low kicks too, very quickly.

Snake in Xing Yi is also associated with locking and grappling actions – we didn’t see any from Tom in this fight, but that doesn’t change the character that Tom is showing. (He’s actually a very accomplished grappler as well).

But what about Sergei? Well, we didn’t see much from Sergei in this fight, but from what we saw I’d vote Bear for him. His stepping is short as are his rounded punches. He’s incredibly powerful, and he landed the first strike of the match on Tom, which was so powerful he almost finished it there and then. Luckily for Tom he managed to absorb it. In our style we always include Bear and Eagle together, so I think Sergei’s got the potential for some Eagle strikes too, but the fight simply didn’t last long enough for him to show them.

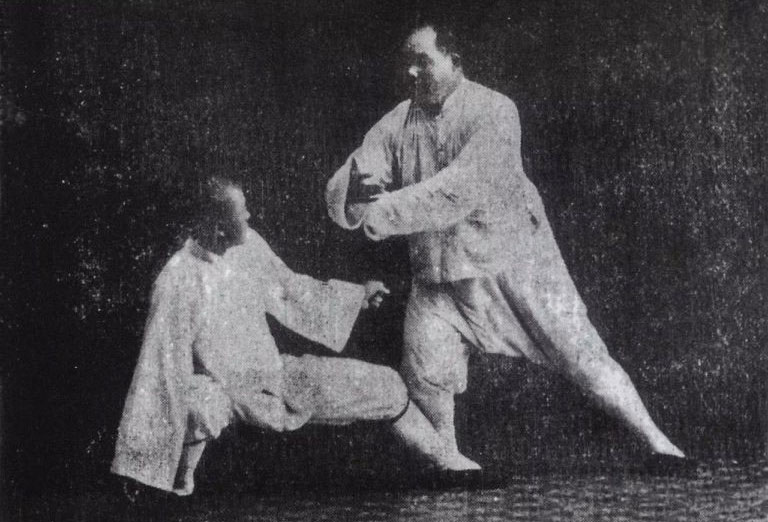

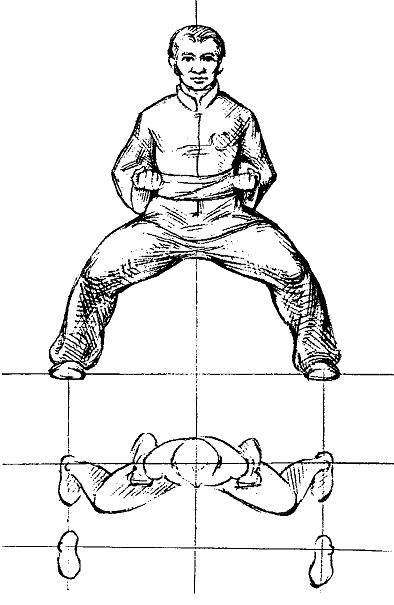

Xing Yi snake (She Xing)

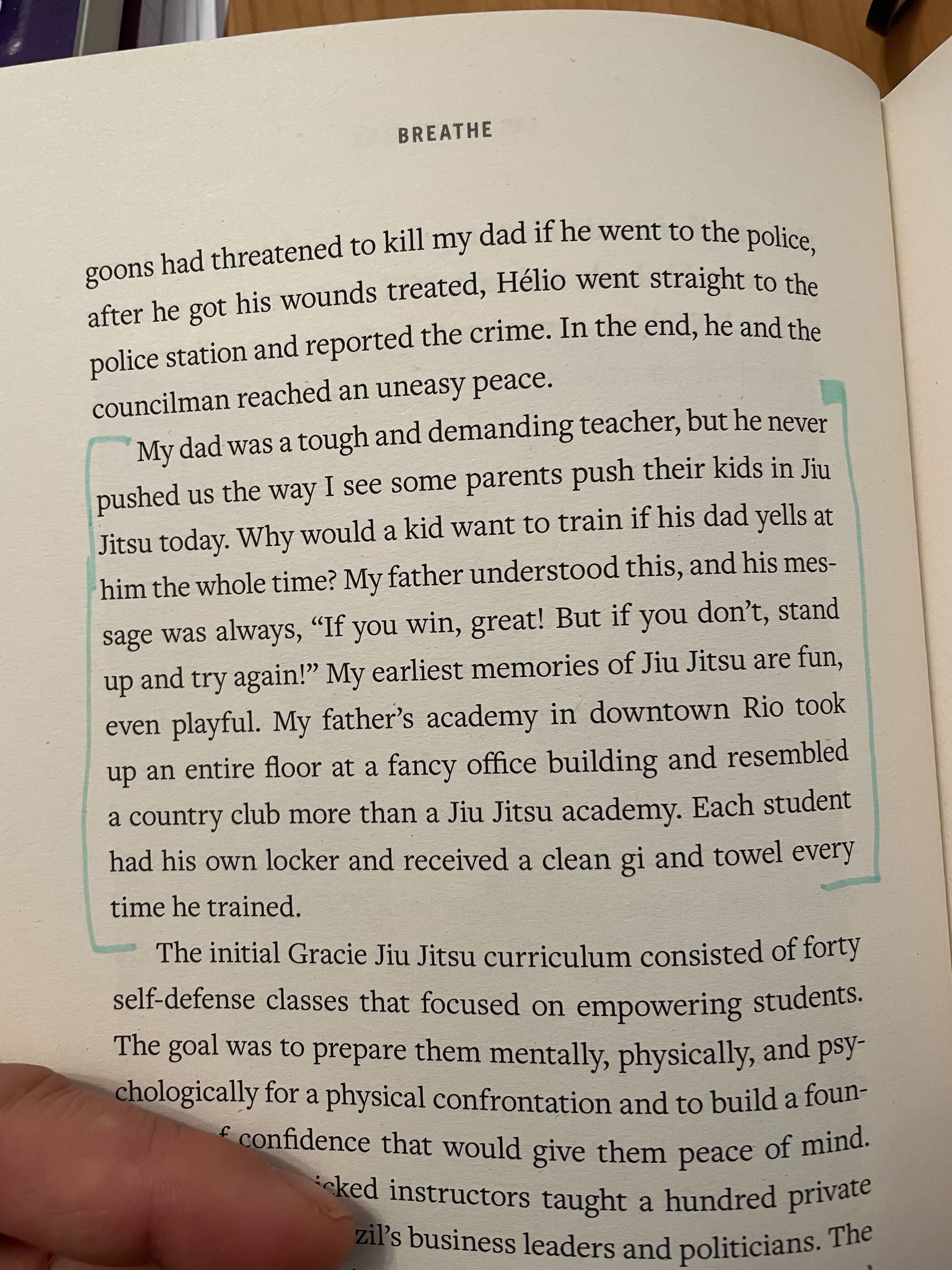

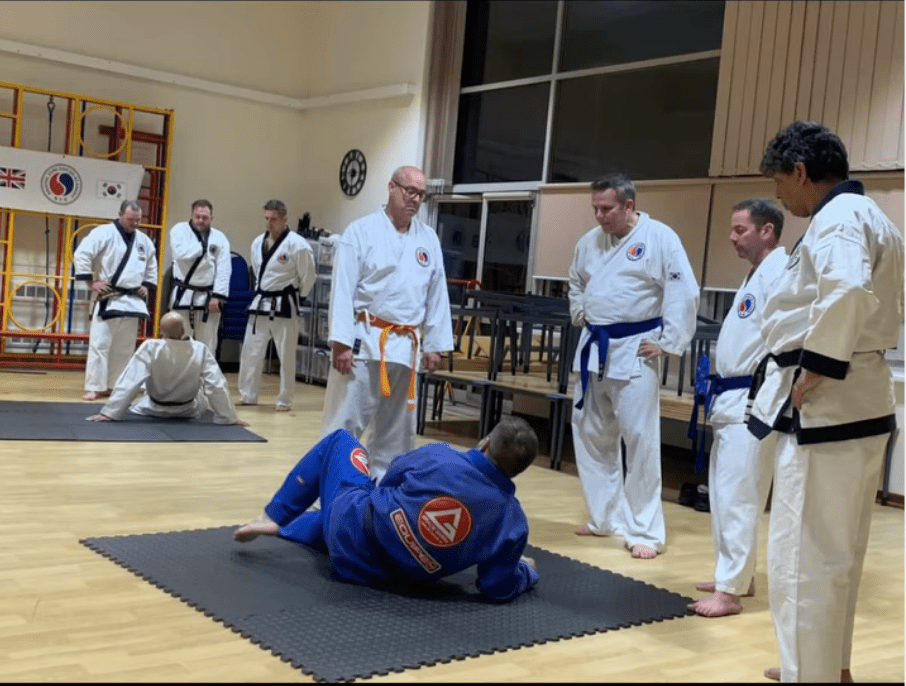

If you’re talking about snake movements performed in Xing Yi then it looks something like this:

You’ll notice you can see the elements I’m talking about here – fast strikes, coiling movements and grappling applications.

Here’s a video of me doing some Xing Yi Snake. I’m showing some berehand and sword here, but you can see it’s all the same thing.

Your mileage may vary

* I suppose this post needs to end with some sort of “this is just my opinion” type of disclaimer. But I find people tend to get offended about everything they possibly can regarding Xing Yi these days, so I’m not going to loose too much sleep over it. And obviously Tom has probably never heard of Xing Yi – I’m just using it as a tool to analyse his fighting style. And if you want to enter an MMA match then MMA training is obviously the best way to train for it, not Xing Yi.

There are different lineages of Xing Yi, it’s been transplanted to different countries, and it’s very old, so it’s quite possible that none of my understanding of Xing Yi snake resonates with your particular lineage. It’s a sad fact that most Xing Yi animals have become just a set of techniques or moves, that have long since lost any connection to actual biological animals – successive waves of crushing political ideology, (both nationalism and communism) imposed on a marital art at the barrel of a gun will kind of do that. I will say however, that my understanding of Xing Yi snake is not really based on a particular style of Xing Yi, or a way of doing the move, but on tying to get back to what real snakes do. And I won’t say I wrote the book on Xing Yi Snake, but I did write one chapter of it.