Alan Watts – what a guy! As the public philosopher entertainer de jour he spearheaded the Eastern spirituality movement of the 60s that took America by storm and forever gave Tai Ch its hippy associations. The lectures on Eastern religions, particularly Zen, he did for a local radio station in California have provided endless motivational video fodder for advertising-packed YouTube videos, and they’re all very good. For example:

He had such a good speaking voice, and could articulate mystical ideas, particularly the idea that existence was simply consciousness playing an eternal game of hide and seek with itself, in ways that Westerners could understand. Of course, the downside of that after you die your words get used to advertise all sorts of things you may or may not have been in favour of. For example, he’s currently doing a voice over for a company selling cruises on UK TV at the moment. I’m not sure what the old guy would have thought of that, but there you go. That’s life! It’s never what you expect it to be.

I’ve heard people say that Alan Watts was a good communicator, but a poor example of the Taoist ideas he espoused. This is mainly because he was an alcoholic who died at the relatively young age of 58 due to related health complications. However, if I look at the 60’s popular philosopher entertainers like Alan Watts and Joseph Campbell, they’re so much more interesting and interested in their ideas than today’s sorry crop of pitiful, grifting, sophists like Joe Rogan, Scott Adams and Jordan Peterson. All of them are usually trying to convince you of some terrible conspiracy theory with one hand while selling you something with the other. At least Alan Watts had enough self respect to be dead before he started trying to sell me cruises!

I saw one of Alan Watts’ videos on YouTube recently, that sparked a few ideas in me. It was to do with the Taoist idea of Wu Wei. It’s called “Alan Watts – The Principle of Not Forcing”

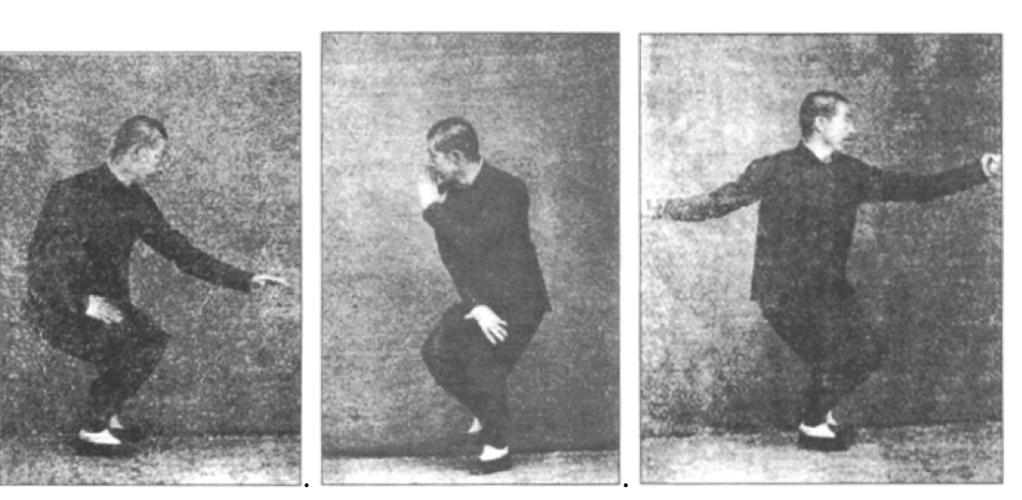

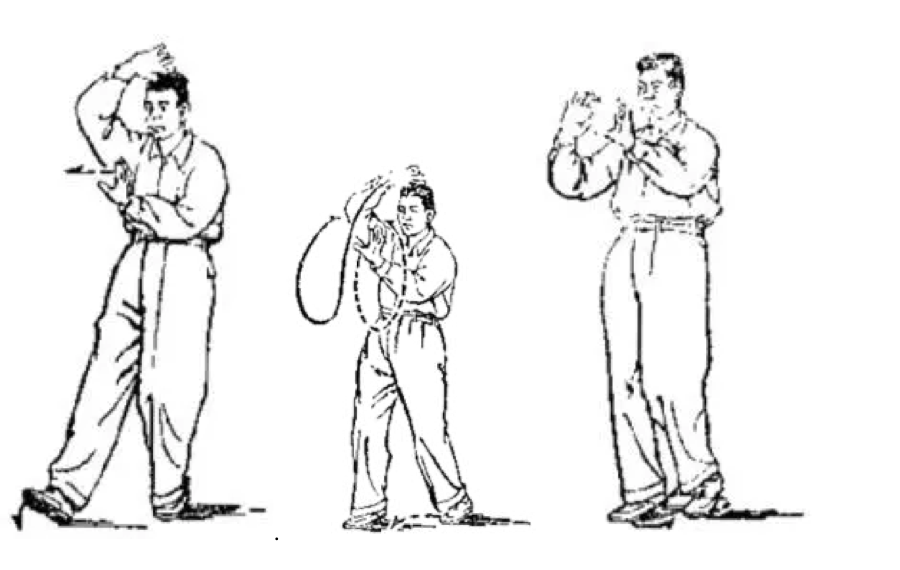

“Not forcing” is Alan’s translation of the Taoist idea of Wu Wei, which is usually translated as “not doing”, or “doing nothing”, however Alan’s translation is much better for martial application. In martial arts, like Tai Chi, it is forcing things that is bad. Alan even mentions Judo in his explanation above.

In English, the idea of doing nothing sounds too passive. Tai Chi isn’t passive. You can’t do a marital art by doing nothing, so I much prefer the translation of “not forcing”. It’s what we aspire to in Jiujitsu as well as Tai Chi. If you feel like you have to force techniques to work in Jiujitsu then it’s not the right way. It might be required in a time-limited competition, but the Gracie family were always famous for not wanting time limits on their matches, mainly because, with their hyper-efficient style of Jiujitsu, they knew they could survive longer than their opponent, exhausting them in the process. When you are forcing things to work you are burning energy, and wearing yourself out.

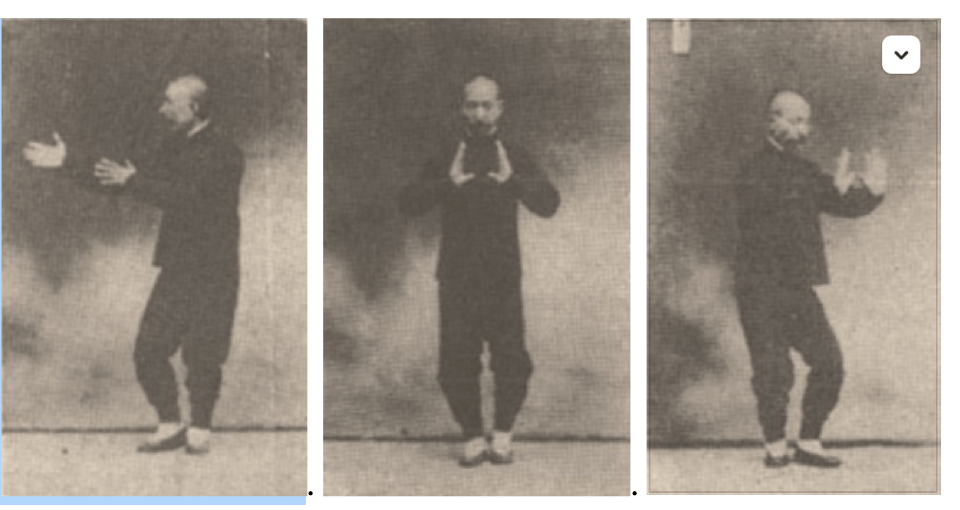

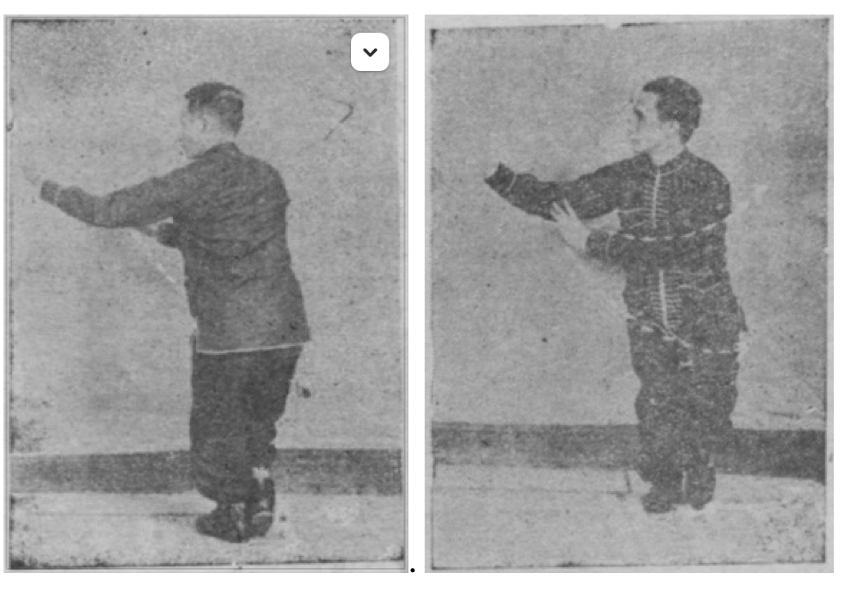

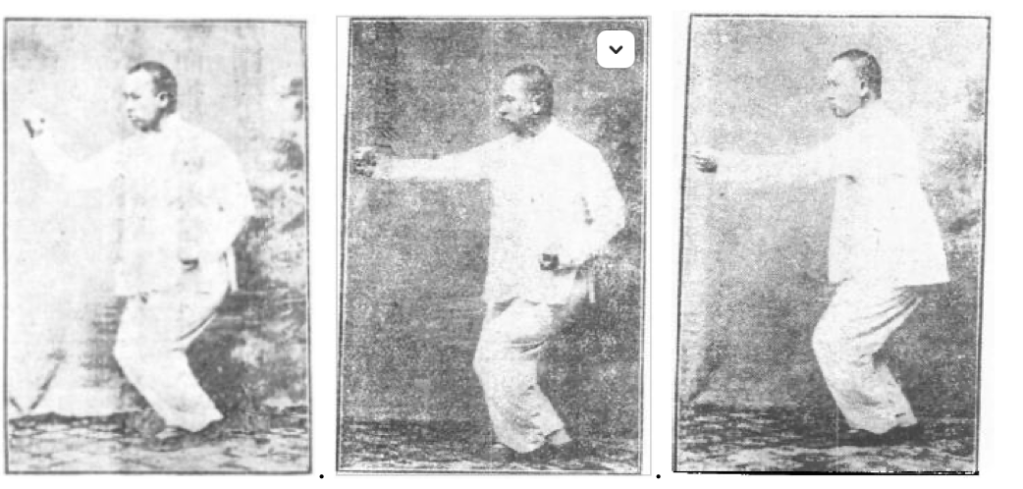

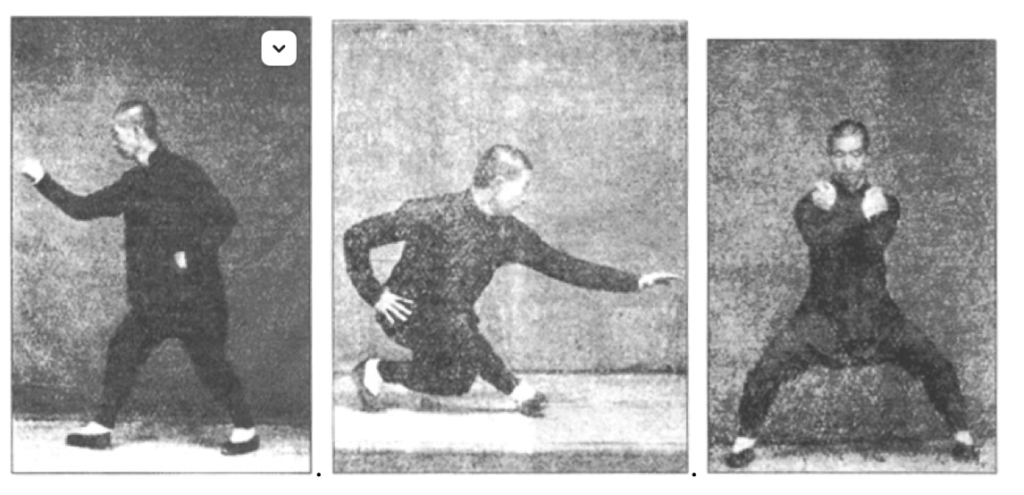

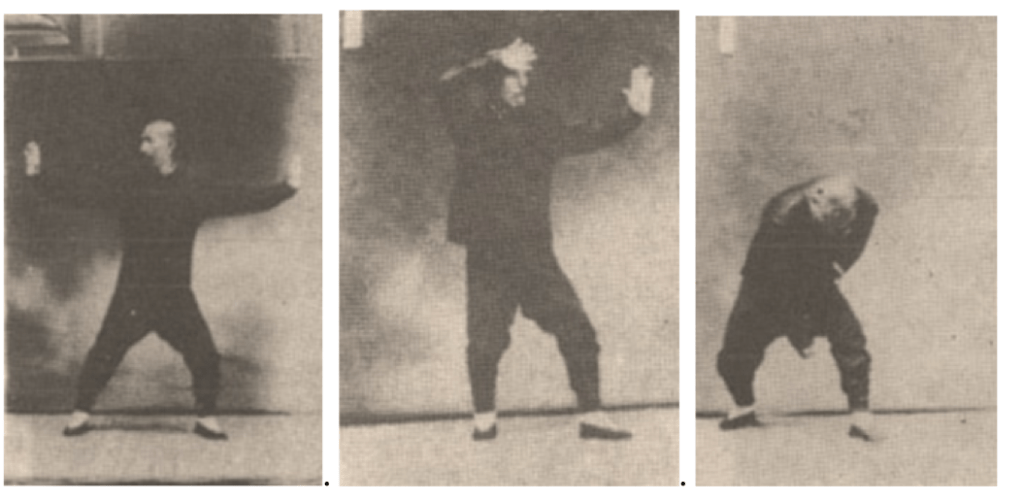

I think different styles of Tai Chi might look at this situation differently though. Yang style, and its derivatives tend to effortlessly breeze through the form. The emphasis is on efficient, continuous movement and relaxation. And while it may look effortless, you feel it in the legs, even if you are not visibly out of breath. Chen style seems to want to work a little harder. The stances are lower, there are occasional expressions of speed, power and jumping kicks. But there is still that emphasis on being like a swan moving through the water – graceful up top, but the legs doing all the hard work below the surface.

But regardless of style, all Tai Chi forms follow the same principle: Wu Wei.