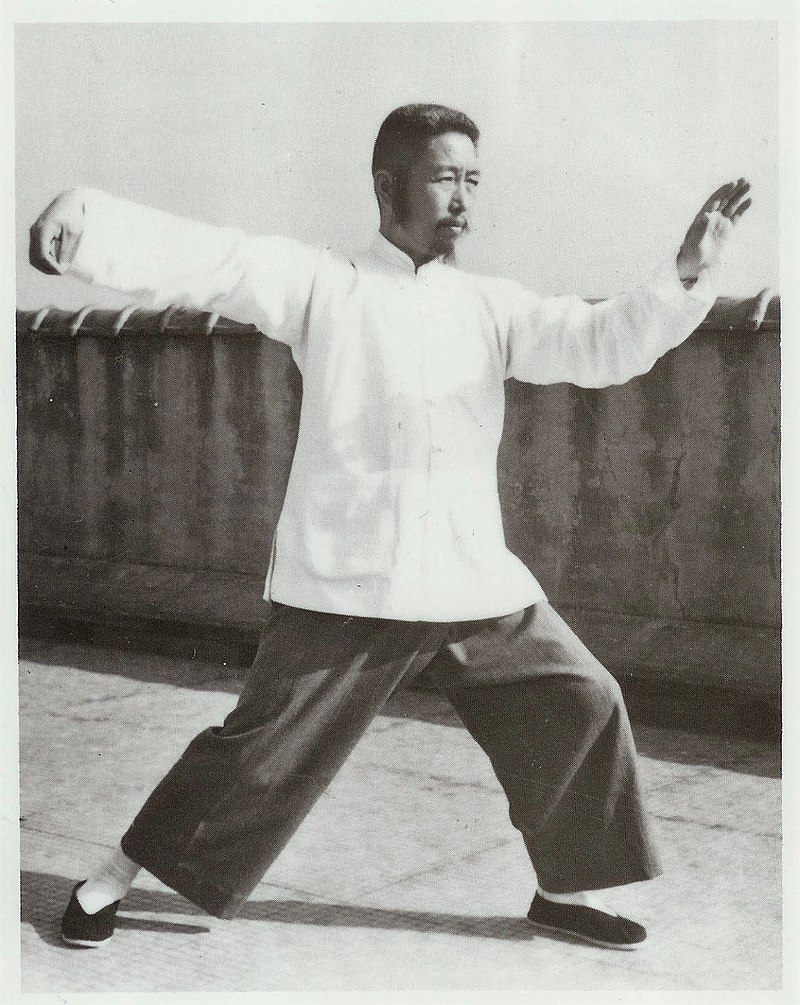

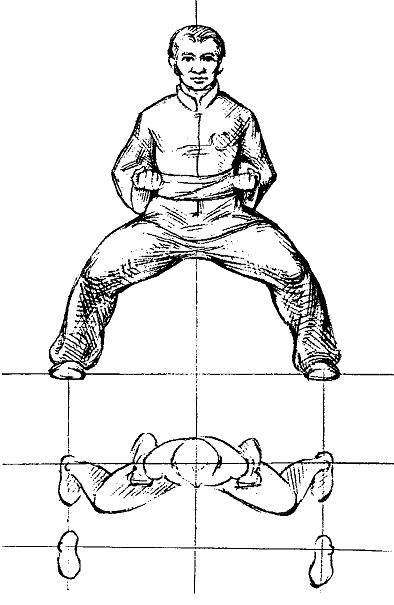

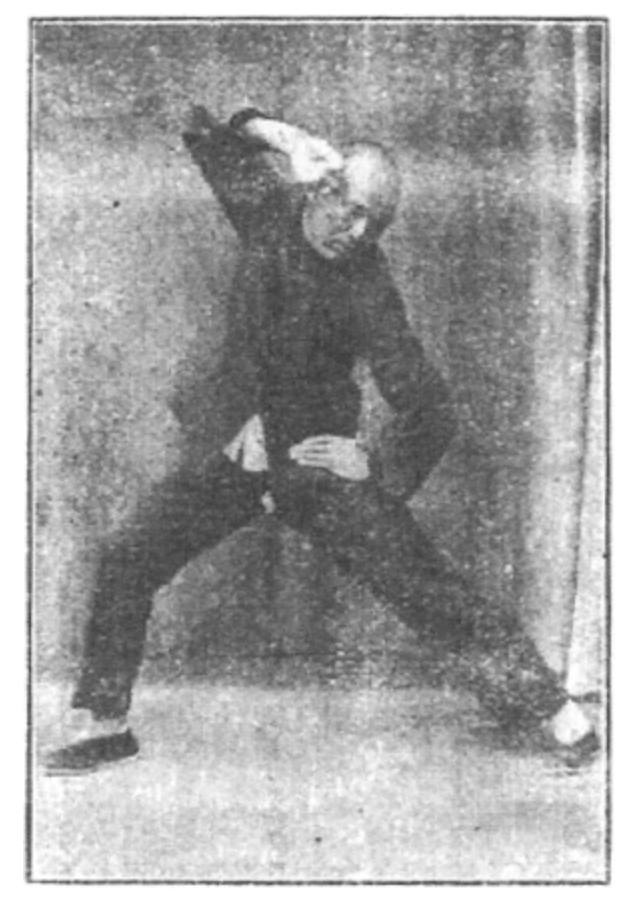

I just saw an advert for a week long “Tai Chi for beginners” intensive with the teacher in question demonstrating a tai chi posture with the head thrust forward, so the chin juts out, the hips and pelvis thrust forward so it looks like he’s doing a bad Elvis impression, the arms awkwardly twisted so the shoulders lock up and the souls of the feet rolling to the sides and coming off the floor, so the ankle joint is not stable.

And yes, he was calling himself “Master”.

I think “buyer beware” is good advice in the tai chi market.

One thing I’ve observed in so many tai chi teachers is this desire to be the teacher way before they are ready. People don’t want to be the student – that’s boring! – they want the glory of leading something, of creating something, of being the person at the front of the class sharing their vast wisdom with their adoring students…

Why is this? I think it’s just ego. I’ve definitely felt it’s twinges in me. It’s a subtle trap that you need to avoid. And one I try actively to avoid all the time when I teach.

It is undoubtedly a nice feeling when people ask you for advice, and look up to you. However, I think it’s nearly always a mistake to want to be that person. People are rarely ever ready to teach tai chi when they start. You could say it’s the curse of tai chi in the western world. That’s why we have people called “master somebody” who can’t do basic tai chi postures or understand tai chi movement leading week-long intensives.

But what do we do about this? After all, somebody has to teach something or there would be no tai chi for anyone!

Perhaps some guidelines if you are teaching:

1. Think of yourself as a coach, or a guide, not ‘a teacher ‘master’. After all, people need to do the work themselves, you can’t do it for them.

2. Don’t let people start to treat you like some guru or master – if they do instantly stop that behaviour developing. You’ll be surprised, a lot of people want a guru to take away all their self responsibility.

3. Self reflect. Are you constantly talking about things you can’t actually do? If so, just stop. There’s never any need for that.

4. The most important thing: Be honest. Tell people what you know, how long you’ve been training, where you got it from. Don’t make yourself into something you’re not in other people’s eyes.

5. Finally, you also need a teacher. Find people you can learn from and don’t stop learning.