Our recent Heretics Podcast series on the history of Tai Chi Chuan keeps generating interesting feedback. Here’s a particularly good one I got today:

My compliments to Damon and Graham on their podcast about the origins of Tai Chi Chuan. I particularly liked mapping martial art history to the general history of the period. From a strict reading of the available evidence the podcast cannot be faulted. Where there maybe problems is in the interpretation provided, which it could be argued commits the error of anachronism. Here is a good quote from a Wikipedia article: “In historical writing, the most common type of anachronism is the adoption of the political, social or cultural concerns and assumptions of one era to interpret or evaluate the events and actions of another”. The interpretation basically argues that Tai Chi Chuan was a bonding exercise in the Imperial Court because of the political decline in the Qing state. A lot more evidence is needed to support the claim that Yang Lu Chan, probably an illiterate low-class bonded servant, was used like an external consultant to go into a large organization and help reassert tradition Confucian values. That looks like an interpretation of Chinese History filtered through the prism of 21th century corporate culture.

Well, that’s an interesting idea. I really like well thought out criticism, especially when it’s delivered so succinctly.

Let’s explore a few of these ideas, and see where it takes us.

I see our podcast on the Myth of Tai Chi as “what Damon thinks really happened based on the available evidence”.

So, there will always be a lot of interpretation involved. History is essentially how you join the dots together. I think what Damon is doing is joining the dots together in a new way that makes a lot more sense than the stories we have been given by our teachers (in some senses the last people you should be asking about real history are martial artists), which all have parts that don’t make sense:

1. The original story we were given was about Tai Ch Chuan (Taijiquan) being created by a Taoist immortal called Chan San Feng. He’s a semi-fictional character who appears at various times throughout Chinese history. Most people who don’t believe in spirits of the ancestors walking amongst us (a common belief in China then) now dismiss this story. Li Yiyu even removed it from his hand written copy of the Tai Chi classics as early as the 1880s. I think this is one for the flat-earthers out there 🙂

2. The next story is that he learned in Chen village where Tai Chi was created by Chen Wanting in the 16th Century. This story was officially adopted by the General Administration of Sport of China who awarded Chen Village, Henan, a commemorative plaque acknowledging its status as ‘the birthplace of taijiquan’, in 2007 (See Fighting Words, Wile, 2017, Martial Arts Studies (4).) however this plaque had to be removed after just two months after a “firestorm” of new claims to the Tai Chi $ appeared, including the newly ‘discovered’ Li family documents.

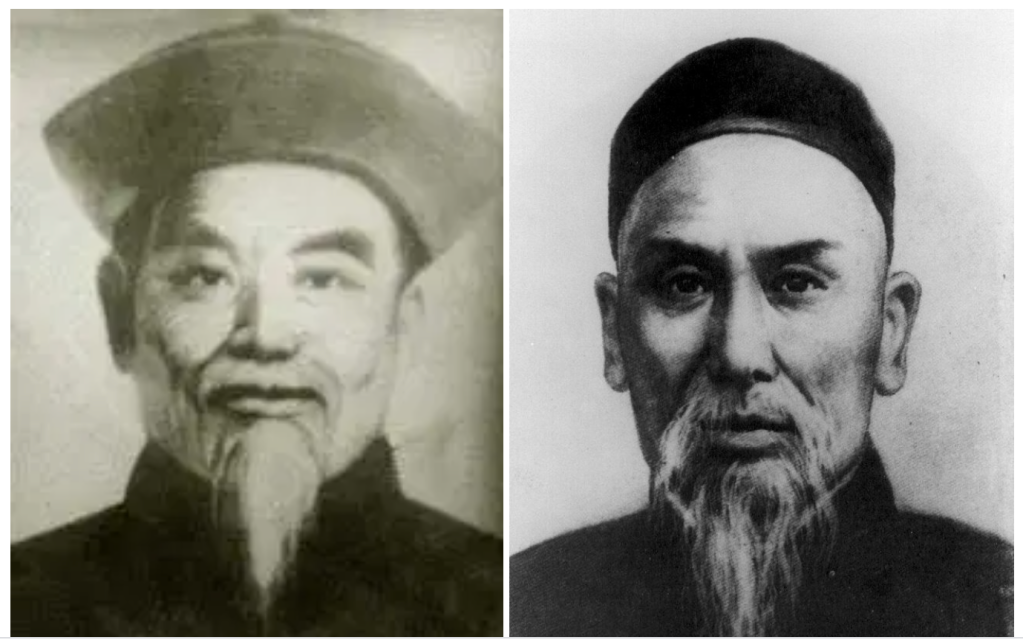

But apart from that the story is full of holes. i) For a start nobody in Chen village used the name “Taijiquan” until long Yang used it. ii) There is also no actual evidence he was in Chen village at all. iii) Wu Yuxiang and Yang Luchan meet in Beijing for the first time, yet both have separate connections to an obscure village in China? iv) Then there’s the issue of why they taught an outsider like Yang, but only him – they didn’t teach anybody else, ever! v) Then there’s all the extra content (lots of other forms, weapons, etc) not found in Yang style, but found in Chen style, vi) Chen village records crediting their martial art to the earlier Chen Bu, not Chen Wanting, vii) the emphasis on silk reeling found in Chen style… the list goes on and on. It just doesn’t add up. However, it still needs explaining why the Chen old form and the Yang long form follow the same pattern (see the upcoming part 6 of Heretics podcast series for Damon’s explanation).

3. There are other theories of Tai Chi Chuan being ancient – really ancient, sometimes a thousand, or two thousand years old (that’s the White Cloud Temple claim) – and coming from Wudang mountain, via various unverifiable people, and ending up in the hands of Yang LuChan somehow – but nobody takes these claims seriously.

Of course, Damon isn’t saying that Tai Chi Chuan was created out of thin air, but rather it is the content of Northern Shaolin arts that Yang LuChan (a good martial artist) knew, adapted to fit certain traditional Confucian Court values thanks to Wu Yuxiang, and with a backstory added by Wu to make it appear ancient.

A class-based society

Chinese society was class-based, and teaching martial arts would make Yang LuChan the same class as theatre performers, i.e. the lowest of all classes.

The caste system is based on the Four Occupations of Confucianism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_occupations

Theatre performers and martial artists are lower than no.4. They were “mean people”: jiànrén.

The noun is also used to mean “bitch” or “bastard”. The pronunciation can be found here: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E8%B3%A4%E4%BA%BA#Chinese

From the Wikipedia article above: “There were many social groups that were excluded from the four broad categories in the social hierarchy. These included soldiers and guards, religious clergy and diviners, eunuchs and concubines, entertainers and courtiers, domestic servants and slaves, prostitutes, and low class laborers other than farmers and artisans. People who performed such tasks that were considered either worthless or “filthy” were placed in the category of mean people (賤人), not being registered as commoners and having some legal disabilities.[1]”

So, Yang LuChan was a Jianren, yet, there he was inside the Forbidden City, teaching (and mixing with) the most high-level people in the system.

I think this can be verified: The only students we know he had were all in senior positions, like Wu Yuxiang, and Wu Quan Yu, for example. Those are the facts of the matter, and viewed through our eyes that does make him something like an external consultant, but only superficially. Compared to a consultant of today the power dynamic would be very different. I imagine Yang would be doing a lot of bowing and kowtowing to these senior people he’s teaching.

But is that anachronism or just a reading of the facts? The teaching of martial arts as a hobby or binding action for the court, was indeed a unique innovation, but I don’t think somebody of the lowest class being used to entertain the court is that unusual at all – there is plenty of historical precedent: Theatre entertainers, for example, were regularly brought to the Forbidden City to entertain the Confucian court, throughout Chinese history:

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre_of_China

“The Ming imperial court also enjoyed opera. However, most Ming emperors liked to keep their music entertainments inside the palace.[24] They performed for the court. ”

Jingxi (Peking Opera) was certainly popular in the Ching court too:

“In music, the most notable development of the dynasty probably was the development of jingxi, or Peking opera, over several decades at the end of the 18th century. The style was an amalgam of several regional music-theatre traditions that employed significantly increased instrumental accompaniment, adding to flute, plucked lute, and clappers, several drums, a double-reed wind instrument, cymbals, and gongs, one of which is designed so as to rise quickly in pitch when struck, giving a “sliding” tonal effect that became a familiar characteristic of the genre. Jingxi—whose roots are actually in many regions but not in Beijing—uses fewer melodies than do other forms but repeats them with different lyrics. It is thought to have gained stature because of patronage by the empress dowager Cixi of the late Qing, but it had long been enormously popular with commoners.” – from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Qing-dynasty

So, I think we can establish Yang in the position we say he is in (the Royal Court). But let’s get to the meat of the matter!

“A lot more evidence is needed to support the claim that Yang Lu Chan, probably an illiterate low-class bonded servant, was used like an external consultant to go into a large organization and help reassert tradition Confucian values.”

I agree, but it’s hard to know what form that evidence could take? The Smith hypothesis is that it was Wu Wuxiang who was performing some sort of re-instigation of Confucian values, and Yang LuChan was just being used as a gun for hire. We know he was there, in the royal court, but the question of what he was doing there is the key issue.

Tai Chi Chuan as Neo-Confucianist martial art

Everybody knows Tai Chi is based on Taoist principles, starting with Yin and Yang. But wouldn’t you expect the martial art Yang and Wu came up with to be more Confucian in flavour than Taoist? Why then was Yang teaching a martial art that people instinctively know is Taoist in philosophy? Tai Chi Chuan (a soft, internal martial art) is, after all, based on those great symbols of Taoism – the Yin Yang symbol, the 5 elements, the 8 Bagua, etc..

So, how do you explain that contradiction? Well, I can add one more piece of evidence. I wouldn’t call it a smoking gun, but it does add to the overall narrative:

If we look at the content of what he was teaching (Tai Chi Chuan) – then you’ll find it kind of is based on traditional Confucian values, rather than anything Taoist. I’ll explain…..

People talk about Tai Chi as being Taoist a lot, but Taoism is this shaggy, messy, nature-loving, outdoorsy, shamanic, magic, smokey, rich, spiritual, earthy thing involving things like spirit possession and exorcism – it’s not very Confucian at all. Or indeed, very like Tai Chi Chuan.

The best description of Taoism I’ve heard was by Bill Porter (Red Pine), who likened Taoism to “house-broken shamanism”.

The philosophy we find in Tai Chi Chuan – yin and yang, 5 elements, 8 powers, etc. uses the symbols of Taoism, but is all very heavy on categorisation – it’s very clean, neat and orderly. In fact, very… Confucian!

Or, rather, it’s what scholars call “Neo Confucian”. At the time that Buddhism was gaining popularity in China, as a threat to Confucianism, the Confucians needed something to combat it, because they had nothing very “spiritual” in their religion, whilst Buddhism and Taoism were both full of spiritual stuff.

The Confucians plugged the gap with what became known as Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism adopted the signs and symbols and ideas of these more spiritual religions (yin and yang, Taiji symbols, 5 elements, etc), but it was really just repackaged Confucianism 101. The scholar responsible for all this was Zhu Xi, who lived during the Song Dynasty, from 1130-1200AD. He effectively sanitised all these Taoist ideas and related it all back to the 4 classic texts of Confucianism. His impact in his lifetime was not so great, but to later periods it was absolutely huge – his ideas formed the basis of the Civil and Martial exams that people had to pass to enter government/senior positions, for example.

Damon did an excellent episode about Zhu Xi’s impact on Chinese society and martial arts as part of the Heretics Xing Yi series (the same Neo-Confucian philosophy ends up being dumped on Xing Yi during a later period).

Here it is: https://www.spreaker.com/user/9404101/20-xing-yi-part-5

Give that episode 5 of Xing Yi a listen. To me it makes sense.

I should add some rumour control, since I think that Tai Chi people will generally not like this Neo-Confucian angle:

1. I don’t think saying that the philosophy of Tai Chi is actually Neo-Confucian, rather than Taoist is a diss to the art – an actual Taoist martial art I imagine would not be as practical! It would be messy, unfocussed and a bit wild. A martial arts form repeated over and over in the same sequence each time would probably be a strange concept to a Taoist!

2. I also don’t want to diss the Chen family – their reputation during the Ching Dynasty was of them being practical and expert martial artists who actually used their martial skills to fight bandits and escort caravans. They were the real deal! Their family martial art is older than the appearance of Taijiquan in the 1850s by far – and as any good Confucian knows, older is always better! 🙂

What matters to me about Taijiquan is that it works, not what you call the philosophy behind it.

Heady stuff. When it comes to tai chi, I’m a small fish in a small pond. This in-depth look at history and origin stories is very interesting, but it makes my head spin. 🙂

LikeLike

This was an extremely interesting read for me. I don’t think of taoism at all in the way you do. The whole messy, shaman, magic, spirit possession and exorcism thing is such an add-on, — way after the way, and short-lived — but the Tao itself is very patterned, as is nature, and I would say, very orderly, as is nature. Weeds and water may appear messy and untamed on the surface, but they grow and move in very exacting ways. For each, internal structure and patterns are repetitive and very precise.

I cracked up at the idea that “A martial arts form repeated over and over in the same sequence each time would probably be a strange concept to a Taoist!” And, the concept of “house-broken shamanism” was equally funny to me. I will delight in examining those ideas further!

Truth is, I know nothing about tai chi, so I cannot speak to that. But in my experience, it is only after long hours of repetition that I can understand when and how to flow beyond repetition. This is why coyote crosses the urban street at dawn.

LikeLike

Tom,

Right – but as Wile points out (Lost classics, page 16) there are no records of Wu Yuxian being in Beijing because there are absolutely no official records of him being anywhere – compared to his brothers he was unimportant. How ironic considering that from today’s vantage point, every Tai Chi practitioner has heard of him and his brothers have slipped into obscurity. Quite possibly he did visit Beijing quite often, or maybe he went to England and had tea with Queen Victoria? We just don’t know 🙂

All we have are anecdotes, 2nd, then 3rd, then 4th hand. And you know how that goes….

Either way, it doesn’t really interfere with the DSH – Damon Smith Hypothesis. The main point being, still no Taijiquan before 1851.

You’ve got us talking about it though, and I think we’ll address this question of Wu’s whereabouts in the next episode. It might well take a whole episode to thrash out 🙂 The Chens might have to wait….

LikeLike

In the conventional history of taiji, Yang Luchan–through his contact with Wu Yuxiang in Yongnian County–is how the Wu brothers would have initially found out about the martial skills associated with Chenjiagou. Based on his interaction with YLC, WYX went to Chenjiagou ca. 1852/3 looking for Chen Changxin, YLC’s teacher (d. 1853), and was recommended (or diverted) to Chen Qingping instead. Of course we’re talking about the heretical history. 😉

But even heretical history should have a basis in local fact as well as broad brushstrokes of history. The Wu family were landed gentry, one of whom (Wu Chengqing 武澄清1800-1884) had passed the imperial examination at the highest (jinshi) level in 1852. In that year, Wu Chengqing was in Beijing taking the imperial examination; working in Leting County in Hebei; in Beijing visiting his younger (middle) brother Wu Ruqing 武汝清 with whom their long-widowed (40 years or so) mother was living; and finally back in Yongnian. After passing the examination WCQ initially drew an assignment to southeast China, but requested (and was granted) reassignment to Wuyang County in Henan, considerably closer to his aging mother and family.

Wu Ruqing retired from his position in Beijing in 1853 and retired back to Yongnian, presumably taking his mother with him. In July-October of 1853, Wu Yuxiang 武禹襄 made his trip to Chenjiagou/Zhaobao. By this time, WYX would have had several years of opportunity to study with YLC, who returned to Yongnian in 1840.

WYX declined offers of imperial service, the last offer being ca. 1860. It is possible that he would have had to go to Beijing in order to decline the offer, but I don’t think so (much easier/safer to decline in writing from afar).

I should have been more precise in what I meant in my previous post by “during this time” with reference to the presence of the Wu brothers in Beijing. I meant the time period–1861 on–referred to by Damon in the episode on Cixi’s ascendancy. There are written records that at least two of the three Wu brothers–Chengqing and Ruqing–had been to Beijing, and Ruqing even lived there for awhile. Much of this is covered in Chengqing’s autobiography, other information comes from county gazetteers of the time–these sources are in the annotations to Douglas Wiles’ “Lost Tai Chi Classics” and Barbara Davis’ “Taijiquan Classics: an Annotated Translation.” Based on these sources, even in the absence of a specific record it would be quite reasonable to assume that WYX had also visited Beijing. What is not clear from available sources is anything indicating the presence of WYX or either of his brothers in Beijing during the time period that Damon is inferring the Wu brothers introducing YLC around and setting up taijiquan as a tool of neo-Confucian powerbrokers.

I think, however, that Damon’s interest in those details is long past. He’s moving on to Yuan Shikai and Chen Yanxi and questions of the provenance of taolu.

LikeLike

Thanks Tom – interesting point about Wu Yuxiang having no verifiable history in Beijing – I’ll do some research on that.

LikeLike

I’ve enjoyed Damon’s monologues in this series on taiji. I think people understand the history given is just Damon’s interpretation, unsourced. The unfortunate part of the narrative is that some key assertions are made that are not true. Wu Yuxiang met Yang Luchan in Yongnian County before Yang went to Beijing. We actually don’t know whether WYX ever went to Beijing. WYX’s older brother did have a position of some importance in the Qing imperial administration, but it was at the county level as a magistrate. There is no extant written record, in a bureaucracy of exhaustive written records, of any of the Wu brothers in Beijing during this time. By contrast, we do have references for YLC appearing in Beijing and being called in to demonstrate at a banquet being held at the mansion of the wealthy Zhang family, purveyors of pickles to the Imperial court (and connected to the Wu brothers …. Damon should look at the sources available for this connection, because it helps support his thesis more clearly than what he’s established only by inference so far).

I think your post today rings true in many important respects. By YLC’s time there was no Daoism in Beijing any more. The Daoist temples all had neo-Confucian hierarchies and the dominant sect in Beijing, Quanzhen, was infused with Buddhist practices and ritual.

I’m very much looking forward to Episode 6.

LikeLike